New nuclear plant put to a test ballot

A non-binding vote on February 13 on the construction of a nuclear power plant outside the capital Bern is seen as a test for Switzerland’s nuclear power policy.

The cantonal ballot could have a key impact on the choice for the sites of two new plants considered by the country’s three electricity companies.

It is widely expected that Swiss voters will have the final say on the construction of new reactors in a nationwide ballot in 2013 or 2014.

Switzerland currently has five nuclear reactors which generate about 40 per cent of the country’s energy but will gradually come off the power grid as of 2019.

Following months of bargaining, the three electricity companies, Axpo, Alpiq and BKW/FMB, in December agreed to apply for two new nuclear stations for an estimated SFr20 billion ($20.8 billion).

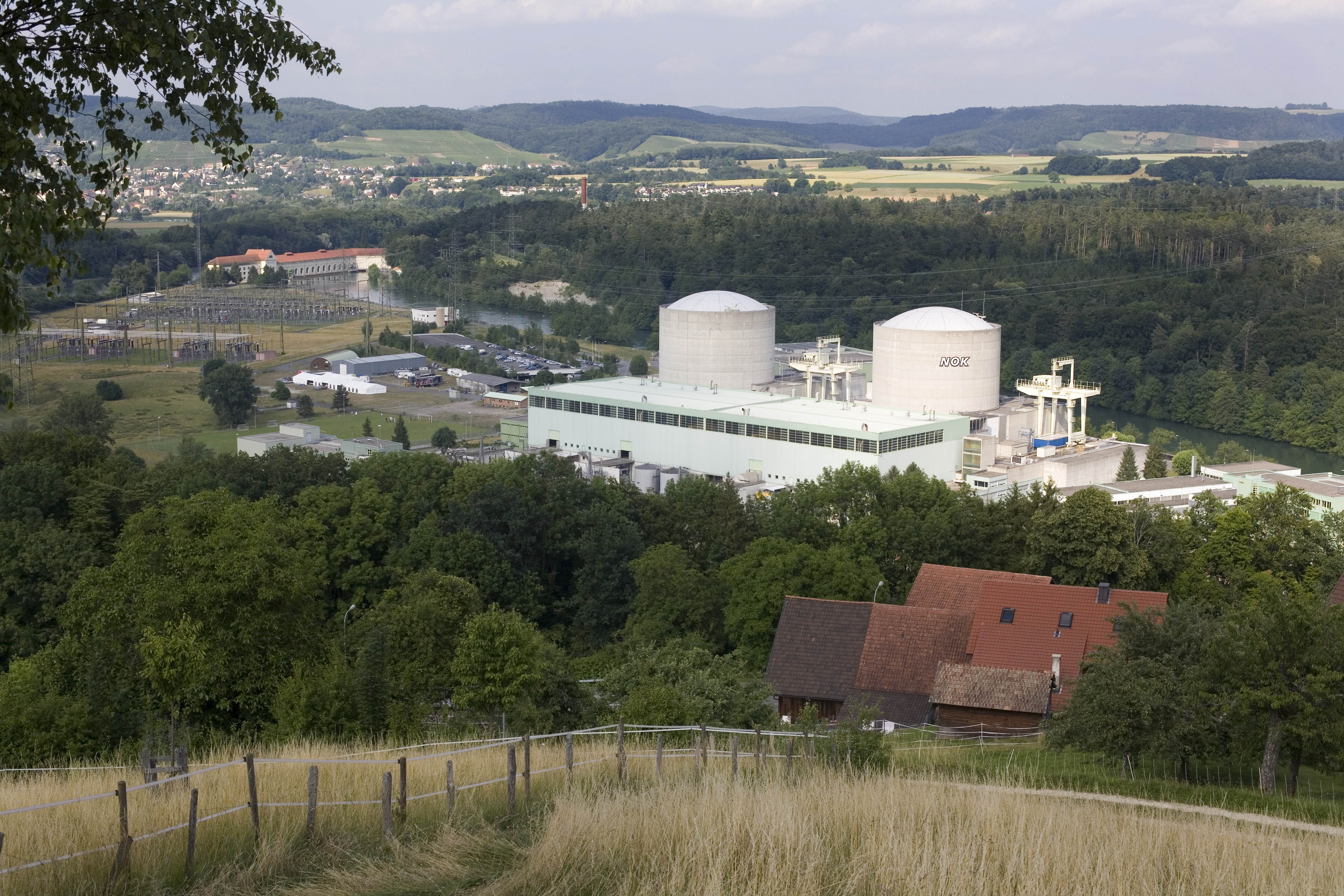

The sites considered include Mühleberg – a few kilometres outside the capital – and two other locations in Gösgen and Beznau, both in northern Switzerland. All of them already host nuclear reactors that came into service from 1969 onwards.

A rejection by voters in canton Bern on February 13 is likely to spell the end of Mühleberg as location for a new plant.

In the past, a majority of voters in canton Bern came out in favour of nuclear energy, but those in the city of Bern recently approved the withdrawal from such energy by 2039.

Entrenched

Over the past few weeks campaigners have put on the table their well-known arguments for a new Mühleberg plant.

Supporters, including Christa Markwalder, a parliamentarian from the centre-right Radical Party, argue Switzerland face an energy shortage in the medium term and the economy needs a cheap and reliable electricity source.

At the same time she stressed the need for the promotion of renewable energy.

“But we have to realistic. Solar and wind energy account for 0.1 per cent of Switzerland’s energy production, while nuclear power contributes nearly 40 per cent,” Markwalder said.

She added that failure to produce electricity inside the country would make Switzerland depended on the import of energy from coal and gas power stations abroad, where often production methods are used which are not necessarily environmentally friendly.

Environment

Green Party parliamentarian Franziska Teuscher countered that nuclear energy was outdated.

“There are much better and less dangerous alternatives today,” she said.

Teuscher, an experienced anti-nuclear campaigner, said more efforts should also be made to save energy.

“Besides, renewable energy from wind and solar power as well as from wood can be reliable sources and replace nuclear power.”

She also referred to a scenario published by the government saying withdrawal from nuclear energy was feasible by 2035.

Risks

Opponents highlight the safety risks of nuclear energy for the environment and the population, but Markwalder appeared unimpressed by the warnings.

Following a visit last year to Chernobyl, the site of the 1986 nuclear incident in Ukraine, she said she remained convinced that it was crucial for Switzerland to be in a position to manage the potential risks of a nuclear power plant by itself.

Otherwise the Swiss would be dependent on others to monitor and oversee the management of nuclear plants.

Waste

Under the Swiss constitution, operators of nuclear power plants are responsible for the safe disposal of their nuclear waste at their own costs.

However, after years of searching, the National Cooperative for the Disposal of Radioactive Waste, known under its German acronym Nagra, is still looking for a suitable underground repository to avoid any danger for people and the environment over 200,000 years.

It is still unclear where the nuclear waste from Swiss nuclear power stations will be stored. A central interim dry cask storage facility for high-level waste was opened in northern Switzerland in 2001.

As part of a highly emotional campaign over the past weeks, it emerged that the authorities did not mention that the project for a new plant in Mühleberg foresees the construction of interim storage facilities.

However, supporter downplay the omission, saying such facilities are part and parcel of any such power plant.

The five nuclear power plants gradually went into service between 1969 and 1984 and have an unlimited duration operating licence.

The operators say the lifespan of the stations runs out between 2019 and 2034.

Spent fuel rods were sent to France and Britain for reprocessing until 2006 when a ten-year moratorium came into force.

The authorities currently examine sites for the construction of nuclear waste disposals to be built by 2020.

A proposal for a low and intermediate waste repository in central Switzerland was blocked by referendums in 1995 and 2002.

In 1990 voters approved a ten-year moratorium for the construction of new nuclear power plants.

In 2003 – three years after the end of the freeze – the electorate rejected an extension or a definite withdrawal from nuclear energy programmes.

In 1969 an experimental power reactor in an underground cavern was sealed and written off following a core meltdown in 1966.

Switzerland has five nuclear power reactors which generate about 40% of the country’s electricity.

Hydro-electric power makes up the bulk of the rest, while about 3% comes from other sources.

Solar, wind, bio-fuel and biogas account for about 2% of electricity production, according to the Federal Energy Office.

(Adapted from German by Urs Geiser)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.