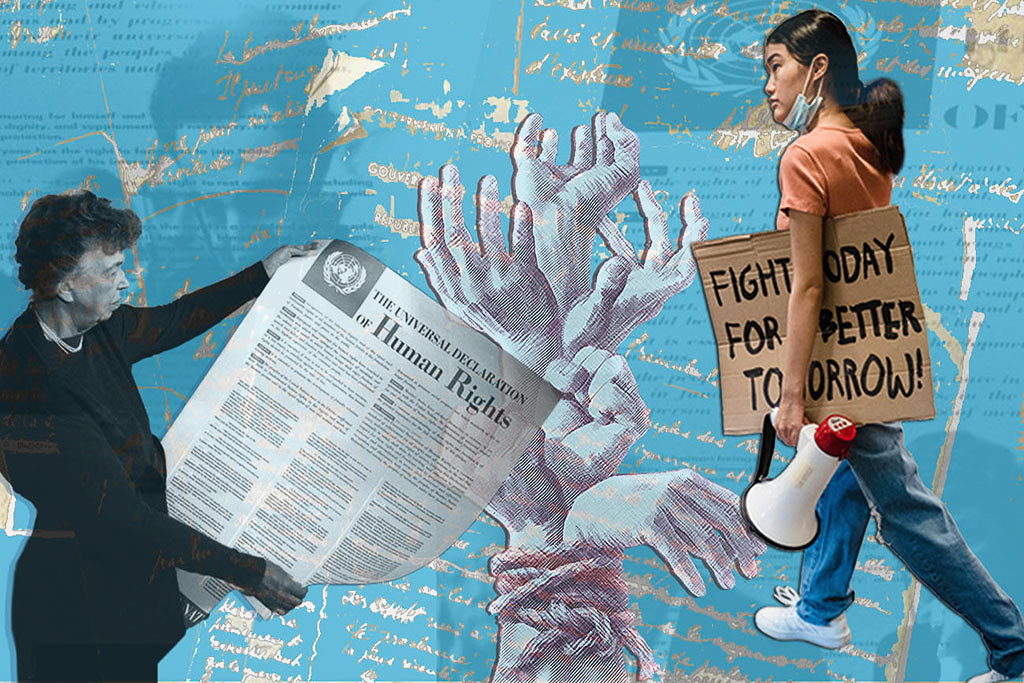

How the Universal Declaration of Human Rights aimed to change the world

The 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights was born out of a desire to ensure that the horrors of the Second World War would not be repeated. As this landmark Declaration turns 75, SWI swissinfo.ch looks at how it came about and whether it is still relevant today.

The Second World War was the deadliest in history. Some 70 million people died, including 50 million civilians. Nazi Germany exterminated some six million Jews – two-thirds of the European Jewish population – who were systematically persecuted, rounded up, their property looted, and forcibly deported along with other minorities considered undesirable, to die in concentration camps. Civilians were bombed. Countries were invaded and their citizens made to work as forced labour. There was mass rape, killing and destruction.

Struggling to emerge from such inhumanity, and with the United Nations taking over from the discredited League of Nations that had failed to stop the war, world leaders said “never again”. They decided to complement the UN Charter with a set of principles guaranteeing the rights of every individual everywhere.

How the Declaration was born

The matter was taken up at the first session of the UN General Assembly in 1946 and referred to the Commission on Human Rights, predecessor to the Geneva-based Human Rights Council.

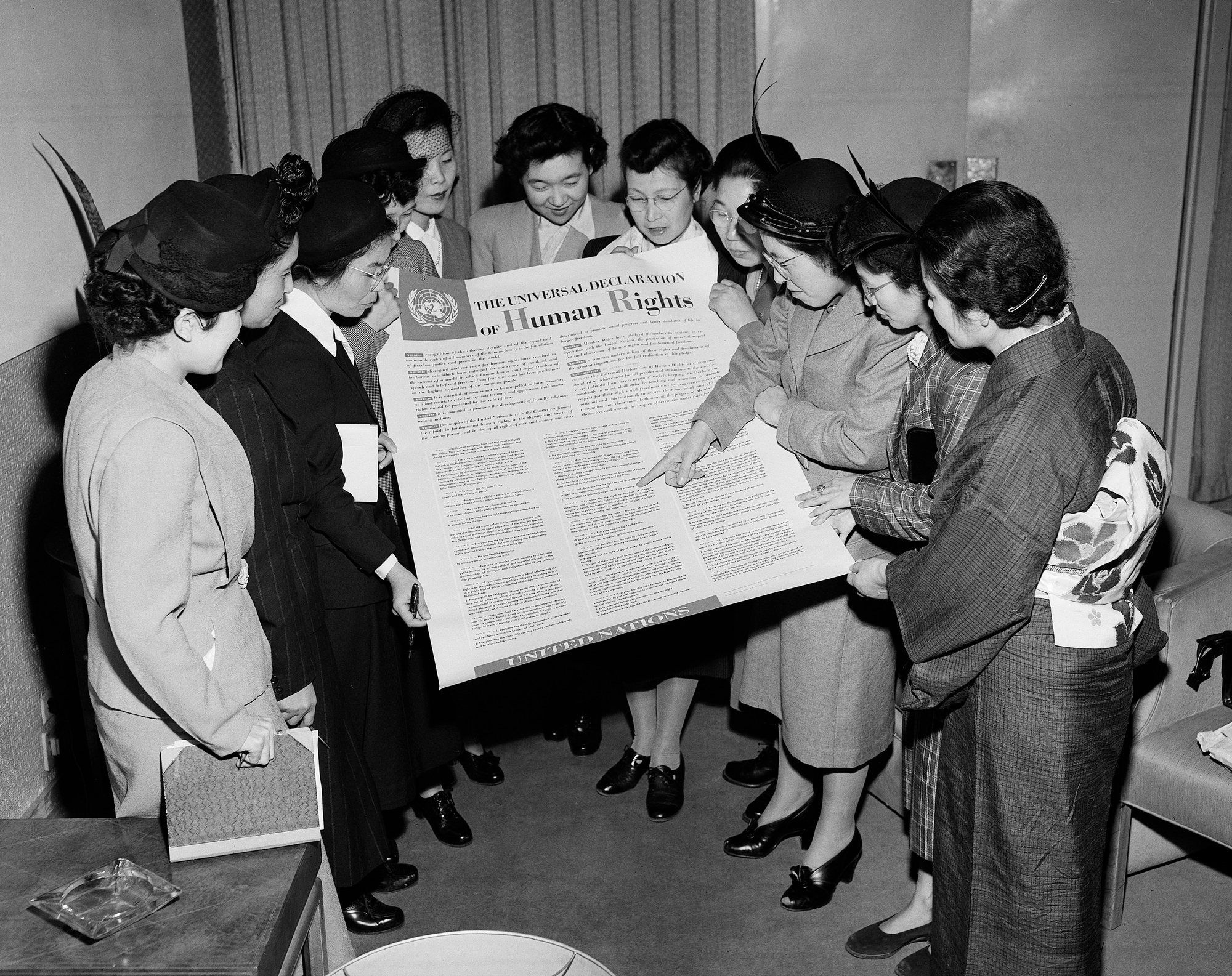

The Commission on Human Rights met for the first time in January 1947 in New York and established a drafting committee for the Declaration. Eleanor Roosevelt, widow of US President Franklin D. Roosevelt, chaired that committee. All the committee members played key roles, but Roosevelt was recognised as the driving force for the Declaration’s adoption. She described it as a “Magna Carta” for human rights.

Other women also played a partExternal link. For example, Hansa Mehta of India, a member of the sub-commission on the status of women, is credited with having got the first words of the Declaration changed from “all men are born free and equal” to “all human beings are born free and equal”.

The final draft was handed to the Commission on Human Rights, which was meeting in Geneva. This document, known as the Geneva draft, was sent to all the 58 UN member States at the time for comments. On December 10, 1948, at a meeting in Paris, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Universal Declaration of Human RightsExternal link (UDHR).

More

UN Declaration of Human Rights – the threshold of a great event

A ‘miraculous text’

The declaration states that “all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights”. It adds they should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood, and that everyone is entitled to the rights and freedoms set out in the Declaration “without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status”. It says that “everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of person”, and that no one shall be held in slavery. The Declaration also makes freedom of movement, speech and association a human right.

UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Volker Türk of Austria has called the UDHR “a very comprehensive, miraculous text”. South African jurist Navanethem Pillay, who was High Commissioner from 2008-14, calls it inspirational. “Imagine what this meant to me and to all of us who were under apartheid and only knew about the racist laws,” she said in an interview with SWI swissinfo.ch. “It meant a great deal to look up to a system of universally accepted standards, of how rights belong to all human beings and they’re all entitled to it.”

Phil Lynch, director of the Geneva-based NGO International Service for Human RightsExternal link (ISHR), says the Universal Declaration of Human Rights “has had a transformative impact on people and communities worldwide, informing and inspiring the development of national laws and policies, underpinning the demands of social movements and civil society actors, providing an important tool for advocates, and enshrining universal values that unite humanity and set out the conditions for all persons to live with dignity”.

How it gave birth to international treaties

The UDHR is seen as the basis for international human rights law. Its principles have been fleshed out in a number of international treatiesExternal link on, for example: elimination of all forms of racial discrimination (1965); civil and political rights (1966); economic, social and cultural rights (1966); elimination of all forms of discrimination against women (1979); against torture (1984); and on the rights of the child (1989).

Pillay sees the Universal Declaration as “our Basic Law”, setting the fundamental principles from which these conventions stemmed. Some countries, such as South Africa under Mandela, have also incorporated its principles into their national Constitution.

But there remains the problem of getting governments to comply. “We’re losing the essence of what the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was and was meant to be in response to cataclysmic events during the Second World War,” Türk told swissinfo.ch in a recent exclusive interview. “In so many situations around the world there is once again this contempt for the other, the contempt for the human being, the contempt for human dignity.”

Who is keeping watch?

The UN in June 1993 organised the World Conference on Human Rights in Vienna, Austria. Its main outcome was the Vienna Declaration and Programme of ActionExternal link, aimed at strengthening human rights work around the world. The Vienna Declaration also called for strengthening the monitoring capacity of the UN, including establishing the post of High Commissioner for Human Rights. This was created in December 1993.

Now the UN has numerous ways of monitoring and trying to make states comply. The “treaty bodies” monitor how states are applying the human rights conventions, while Special Rapporteurs and fact-finding missions composed of independent experts look into specific human rights issues or country situations.

For example, the Child Rights CommitteeExternal link recently reviewed seven countries’ implementation of the child rights treaty, expressing serious concerns about corporal punishment in Azerbaijan and sexual violence against girls in Bolivia, among other things. Countries are expected to report back on how they have followed the UN recommendations. Special Rapporteurs, for example, recently urged Zimbabwe’s presidentExternal link to reject a bill they said would severely restrict civic space and the right to freedom of association.

These bodies and experts report to the Human Rights Council, which meets at least three times a year in Geneva.

Does the Declaration need an update?

“I would say there is a need to update it, to spell out other rights that have not been entrenched as well as they should have: the rights of indigenous people, the rights of women, rights of children,” says Pillay. “Otherwise, I have utmost faith in the UDHR as a standard. You can’t argue with those principles.”

Lynch says that more than updating, the UDHR needs implementing, so that states and non-state actors violating human rights are held accountable. He says this requires national laws and constitutions which enshrine rights, independent courts and tribunals, and “a vibrant and independent civil society and human rights defenders”.

Current High Commissioner Türk says the Declaration should be seen “not as a relic”, but as holding fundamental principles that provide answers to present and future problems.

Asked at a press conference in December if he would change anything in the Declaration drawn up 75 years ago, he said he would rather appeal for it to be interpreted in light of present concerns. “I would say to every leader today, please read the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, use it, and think of it as your obligation to act.”

Edited by Imogen Foulkes

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.