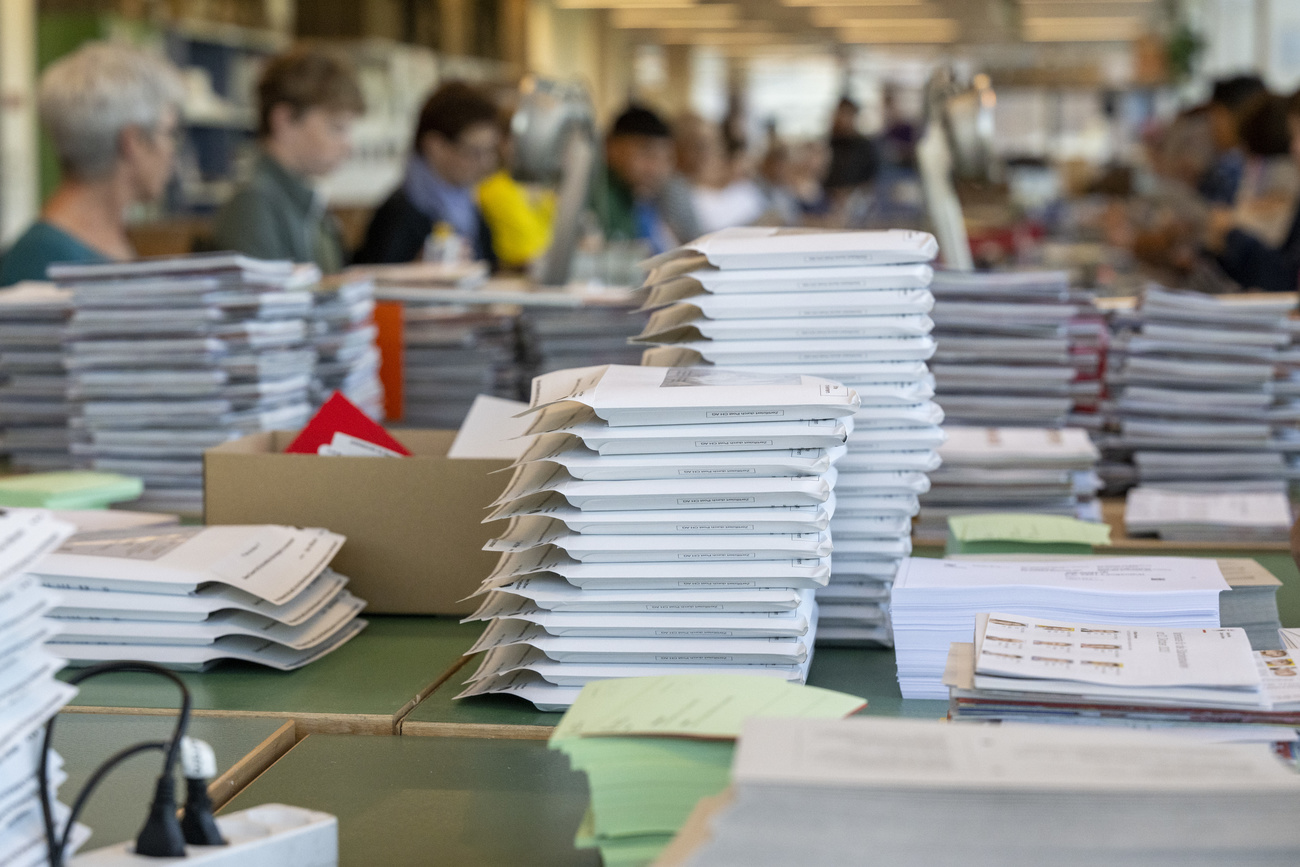

Should Swiss voters worry about foreign influence during elections?

Less than a week before the Swiss go to the polls, a classified intelligence report has emerged that reveals a possible Russian influence campaign to divide public opinion. How susceptible are the Swiss to this type of propaganda?

The focus of the intelligence report, seen by the NZZ am Sonntag, is a blurry video shared on X (formerly Twitter) in September that’s meant to show migrants in a bad light. In it, a Black man appears to be urinating on a street in the town of Baden, northern Switzerland. The video was viewed hundreds of thousands of times, says the newspaperExternal link, although it’s unclear when it was actually shot.

The Federal Intelligence Service (FIS) says in its classified report that “most of the accounts that drove the distribution of the video are probably not authentic” and are likely of Russian origin. “In the information space, Russia is actively exploiting the issue of migration to influence Western states,” the FIS is quoted as saying.

By casting migrants as threats to societal norms and security, Russia’s aim is to “stir up fear and strengthen polarisation between and within Western societies”, it adds. Migration has been a topic of debate during the current election campaign.

The FIS, when contacted by SWI swissinfo.ch, said it would not comment on the NZZ story or on the content of its classified report.

Real users versus bots

Whether the video is actually achieving its aim to stir up fear is hard to say. Daniel Vogler, the deputy director of the Research Center for the Public Sphere and Society at the University of Zurich, points out that few people in Switzerland actually get their news on X – a mere 7%, according toExternal link the 2023 Reuters Digital News Report.

The reach of the video could also be limited by the fact that it was largely spread by bots.

“A so-called bot network will retweet their own message,” Vogler says. “But did real users or even users from Switzerland see the post? If it’s only being reposted by bots, it’s not likely many people actually saw it.”

More

Does social media fuel fake news in Switzerland as much as in the US?

Vogler also doubts the ability of this type of post to divide public opinion. Research arising from the Covid pandemic shows that disinformation campaigns are usually targeted at a specific audience. Messages that confirm a group’s views will be shared within that group.

“This can lead to more polarisation in the long run, but these single incidents themselves won’t worsen polarisation,” he says.

But if the aim of an influence or disinformation campaign is to undermine trust in the political system, then it matters little how many people have actually seen the message. It just needs to be out there, in the pages of a newspaper, for example, that such campaigns exist.

“By making these threats salient, they’re already successful,” Vogler says. “Now people are thinking, ‘we have state actors abroad trying to influence our political system’.”

Trust and resistance

It’s unclear just how widespread such influence campaigns are in Switzerland. In its latest situation reportExternal link, the FIS says Russians, Chinese and Iranian intelligence services, among others, engage in espionage and other activities, including political interference, and that it regularly receives information about “influence activities”. But in most cases, it cannot investigate them if they are not connected to an illegal activity.

The debate about regulating online information in Switzerland has intensified with the adoption in the European Union (of which it is not a member) of the Digital Services Act, which holds the big tech platforms legally accountable for the content posted there. Vogler was among the contributors to a report commissioned by the Federal Office of Communications exploring different measures to fight disinformation. The question of regulation remains a difficult one, he says.

“Free speech is highly valued in Switzerland, so it’s difficult to have to say this is ‘false’ information and we should forbid it – no one wants to have this task,” he says. The report, which has just been submitted, suggests indirect measures, such as greater media literacy, could be a more successful strategy in the long term.

The existence of the video may have emerged at a sensitive time for voters, with just days to go before the federal elections, but Vogler says the Swiss political system of governing by consensus can resist attempts at influence. The Swiss people also continue to have high trust in their public institutions – and research shows that this trust builds resilience to disinformation.

“[The influence campaign] might mobilise a few right-wing voters, but it won’t change the outcome of the election,” Vogler says. “The system is still very resilient as a whole.”

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.