Solutions sought for immigration conundrum

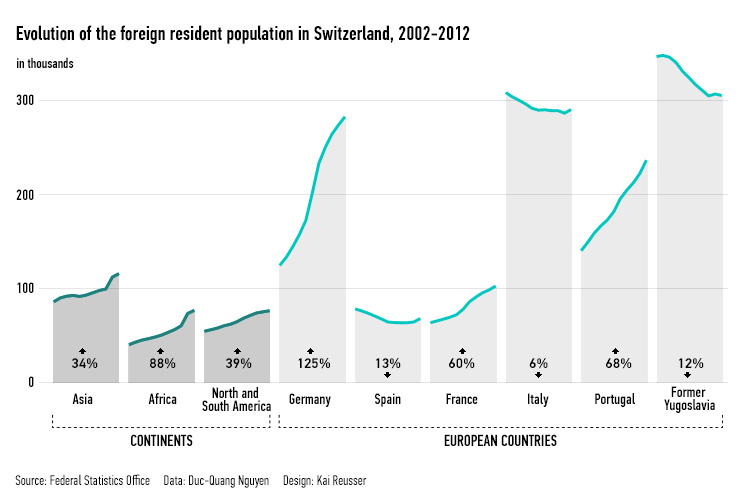

How can February’s vote in favour of limiting immigration be implemented without harming relations with the European Union or damaging the economy? Many proposals have been made, but each seems to have more opponents than supporters.

Quotas, as stipulated in the wording of the initiative, are incompatible with the free movement of people agreed between Switzerland and the EU.

Since Brussels has so far shown no willingness to compromise on this, Switzerland faces a dilemma: should the initiative be implemented through quotas (as its proposers want), which would endanger the country’s bilateral agreements with the EU?

Would it be better either to set no quotas at all or very large ones, although this would anger the initiative’s supporters? They have already threatened to call another vote in order to get the first one implemented should this happen.

In short, solving the problem is like squaring the circle.

EU quotas?

Switzerland has been using a quota system for years to control the number of people coming to work from third countries – those outside the EU and EFTA (the European Free Trade Area, consisting of Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway in addition to Switzerland). Every year the Swiss government sets the maximum number who will be accepted. In the past few years this has been 8,500 (see infobox).

The Employers’ Association does not think much of the idea of extending the quota system to workers from the EU and EFTA.

“Even if the EU were to agree to this – and up to now there has not been the slightest indication that it will – this would not be a practical solution as far as the economy is concerned,” said Daniella Lützelschwab Saija, a member of the association’s management. “To claim that this is a simple matter is simply wrong.”

If quotas are to limit the numbers of new arrivals to any appreciable extent, there is likely to be a fight over how they are allocated. Sectors like agriculture and the hospitality and construction industries, which recruit between 29% and 34% of their labour force from the EU, have already announced that they will resist should they be disadvantaged in comparison to sectors that create greater added value.

“It is essential to avoid fighting over allocations,” said Lützelschwab Saija, without suggesting an alternative.

There has been a quota system for citizens of countries outside the EU and EFTA for several years.

The quotas are set annually by the government: in the past few years they have stood at 8,500.

The figures are based on the needs of the Swiss economy. An employer applying for a permit for a foreign national has to prove that the person is highly skilled, and show that no Swiss and no citizen of an EU or EFTA state is available for the specific job being offered.

A decision is taken by three official bodies: the Federal Migration Office and two offices from the relevant canton: that for migration and that for labour and the economy.

Employers have a good idea of whether their applications are likely to be successful, so they only apply where they are likely to be accepted.

The would-be employer has to submit a large number of documents, the process lasts between five and ten weeks, and the costs are high. Employers complain of the insecurity in not knowing in time whether their submission will be accepted, which makes planning difficult.

Plenty of ideas

The Swiss Association of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises has more specific suggestions. It has put forward a model for regulating which foreign workers could stay in Switzerland and for how long. Quotas should be allocated not by sector and canton, but by permit type, it suggests: skilled immigrants would be eligible for permits allowing them to stay and to settle, while less highly qualified people would get short-term permits.

The economic think tank Avenir Suisse would like to avoid fixed quotas for the moment. Instead, it thinks an upper limit to population growth should be set. Until at least 2020 immigration should be curbed by voluntary economic instruments, and by measures taken at a federal and cantonal level. This would preserve the free moment of people, it claims. Quotas would not be introduced before 2021, and then only if immigration had not fallen to the desired level.

The centre-right Conservative Democratic Party has suggested combining partial free movement, quotas and a maximum limit on immigration overall.

Since Switzerland has a higher proportion of foreigners (23%) than any EU country apart from Luxembourg, the party says immigration should be limited to the EU average. Until then, complete free movement should apply.

Cross-border workers – who live in a neighbouring country but work in Switzerland – are also affected: they should be subject to quotas and Swiss citizens should be given preference.

Border cantons have requested greater latitude in applying the new provisions. Canton Geneva, which rejected the initiative, fears that if quotas are too low this will endanger its economy.

Even the Italian-speaking canton of Ticino, where 68.3% of the population voted in favour of the initiative, has asked to be allowed to decide for itself, and wants its specific characteristics to be borne in mind.

Hans-Ulrich Bigler, head of the Association of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises, has gone so far as to suggest that cross-border workers be exempt from the quota system altogether.

Contradictory expectations

The various ideas all have one aim in common: the bilateral agreements with the EU should not be put at risk – a view shared by the government, which will submit its first proposal on the implementation of the initiative by the end of June, suggesting benchmark figures for a quota system.

But so far there are no signs that any proposal acceptable to the EU will curb immigration to the extent that the rightwing Swiss People’s Party is demanding. The party has meanwhile stressed that it wants the initiative – “which it launched almost single-handedly in the teeth of resistance from business circles, the government and practically all the other parties” – to be properly implemented.

Return to the 70s

But the People’s Party has not put forward any concrete proposals. The party seems to want to bring Switzerland back to the rigid quota system in force between 1970 and 2002. For Heinz Brand, the party’s migration expert, this is a “familiar” solution, and hence one that can be easily applied.

Before the agreement on free movement came into force, the immigration of foreign labour was controlled by the state. The quotas to be admitted were negotiated between the economic sectors, the cantons and social partners. Despite the efforts at limiting immigration, the actual numbers of people entering the country frequently exceeded the maximum allowed, since the quotas did not take into account family reunification and illegal workers.

Brand plays down concerns that the reintroduction of a similar system would be incompatible with free movement of people.

“You have to discuss with the EU and renegotiate the agreements,” he told swissinfo.ch. The People’s Party has also said it is prepared to abandon the bilateral agreements, but is certain that the EU has every interest in renegotiating them.

The trade unions reject the party’s proposal out of hand. In their eyes the old quota system had obvious limits.

“Studies have shown clearly that jobs were insecure, and that wage dumping and illegal working were major problems. There is talk today of a return to the status of seasonal workers as if people have forgotten the awful situation these people found themselves in, frequently forced to live far away from their families,” said Daniel Lampart, general secretary and chief economist of the Trade Union Federation.

Since they lacked many of the rights that today are taken for granted, the seasonal workers often had to hide the children they did not want to leave behind at home but whom Switzerland refused to accept.

Although the debate in Switzerland has focused on workers, asylum seekers are also affected.

The vote sets a ceiling on the number to be admitted.

Many experts warn that this is incompatible with international law, which says that asylum seekers have the right to a fair hearing and cannot be returned to a country where their lives may be in danger.

A two-class system

One of the key ideas being brandished by the People’s Party to limit immigration is indeed to restrict the right to family reunification. In 2013 about 50,000 people came to Switzerland by virtue of this right – 32.2% of the new arrivals.

For Brand and his party, “anyone who comes to Switzerland on a short-term permit [less than one year, renewable] does not need to bring along his wife and children. So L permit holders will not be able to take advantage of family reunification. But for people who stay longer, this right will be guaranteed, as long as they can prove that they have sufficient finances.”

In other words, the People’s Party is proposing a two-tier system, paying special attention to more qualified workers and those who have every chance of being able to integrate.

These provisions are also unlikely to please Brussels. Family reunification is in fact one of the pillars of free movement and the EU has never been willing to compromise on it, not even in the special case of Liechtenstein, which already has a quota system.

The centre-left Social Democrats have already abandoned any thought of finding a solution to this intractable problem. As far as they are concerned, the initiative and the bilateral agreements are “totally incompatible”.

Claiming that voters were unaware of this before they cast their ballots in February, the Social Democrats are making noises about calling a “corrective vote”.

(Translated from German by Julia Slater)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.