Google Maps – a Swiss story

Few people know that behind Google Maps lies a Swiss entrepreneur’s intuition and Switzerland's extensive experience in cartography. This is how the Alpine country contributed to the success of the world's most-used mapping platform.

“Everyone in Switzerland loves maps,” declares Zurich engineer Samuel Widmann. Long before his time, Swiss cartographers were depicting every detail of the landscape, from paths to country roads, from peaks to valleys, and from rocks to trees. That was until digital images came along, followed by Google Maps, which made Widmann rich.

Sign up for our free newsletters.

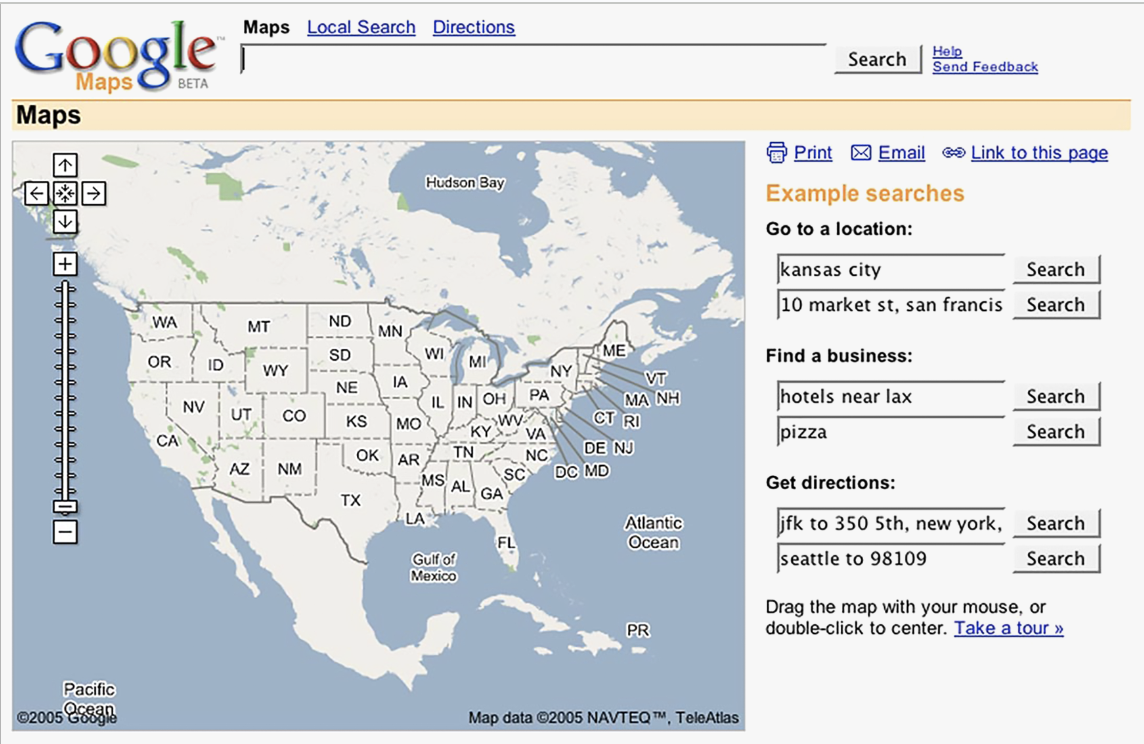

Before the Californian Web search giant created the world’s most widely-used online mapping site in 2005, Widmann and his team were already collecting satellite and aerial images from their office in Lucerne in central Switzerland. Their goal was to create a geospatial database with which to digitally map the entire world.

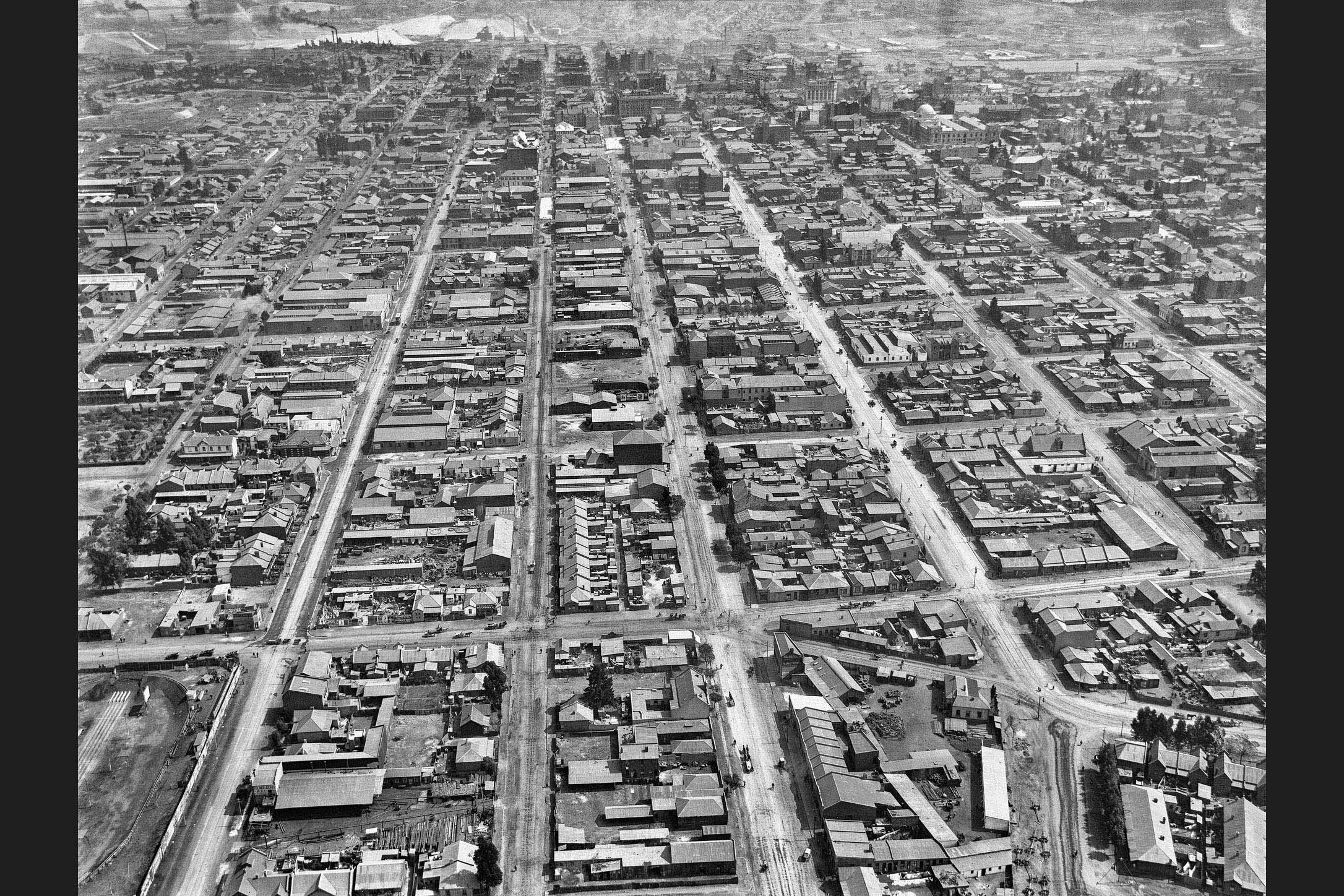

The idea seemed crazy at the time, but Widmann believed in it. He had experience: back in the 1990s, he had started taking photographs from running cars to make accurate digital maps of Swiss roads. The Internet was still in its infancy and there were only a handful of mobile phones around, but Widmann sensed that screens would revolutionise the way people consulted maps.

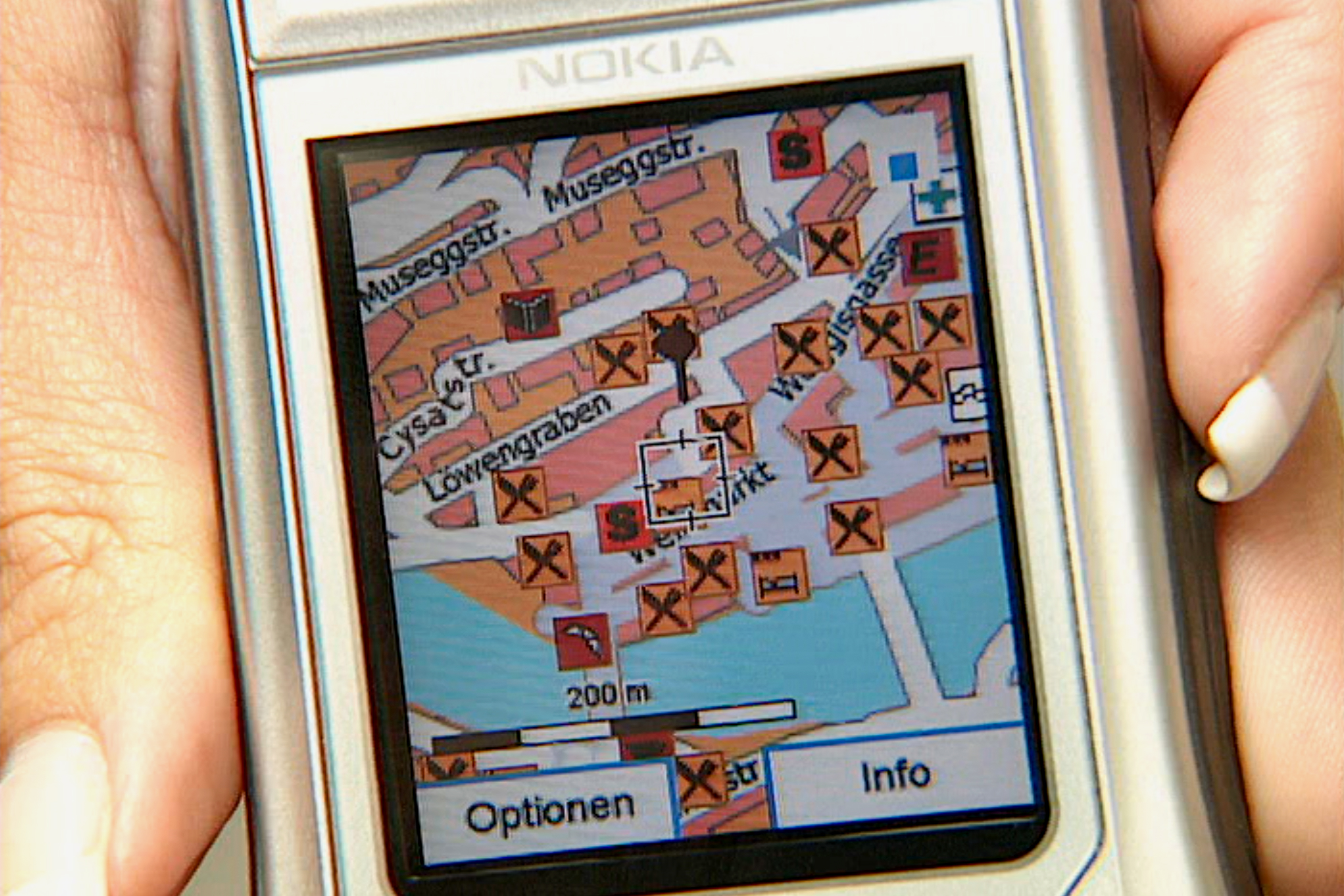

He went even further when he joined the Lucerne-based company Endoxon in 2001, which combined images collected from all over the world with elements of traditional maps to make them easily understandable for anyone. This was the future of maps, according to Widmann. He was not wrong.

Switzerland, birthplace of a visionary project

Switzerland was the perfect place to test the possibilities of this visionary idea, thanks to its small size and a long history of cartography.

“We were the first in the world to have super-accurate maps and aerial images nationwide,” says Widmann. The Swiss federal authorities also offered extremely accurate geolocation services. In the late 1990s, Swiss Post had digitised all the country’s addresses through a project in which Widmann was involved.

The challenge was to extract data from the images accurate enough to train computer models to recognise elements of the landscape. “We wanted to get to the point where algorithms would be able to tell us ‘Hey, here’s a street, here’s a shop, here’s a building’,” not just in Switzerland, but all over the world, Widmann explains. To do this, his team required many expensive databases and powerful servers. It was the dawn of the hyper-ambitious and almost visionary project that would later be known as Google Maps.

Two Danes and a Swiss at the origins of Google Maps

Google entered the equation with perfect timing. It was 2004 and the Californian company had just opened a small subsidiary in Switzerland, which at the time had a few dozen employees. At the time, the Web search giant was making several strategic acquisitions with the idea of creating the most powerful geographic service on the internet. Among them was the startup of Danish computer scientists Lars and Jens Rasmussen, who had launched a Web application with searchable, scrollable and interactive maps.

Google wanted to integrate information normally found outside of maps, such as the name and geolocation of restaurants, cinemas, shops and other venues near the search point. Put in charge of this mission, the Rasmussen brothers realised the potential of Endoxon and contacted Widmann. “It was an incredible site… what they did was a thousand times better than anything else,” Lars Rasmussen told the BBC in 2022, admitting that Endoxon had a commercial advantage over Google.

The reason Widmann’s company had gone unnoticed, according to Rasmussen, was that it was based in Switzerland instead of the US and it was not called Google. In 2006, Google acquired Endoxon and Widmann joined the company. He would head the Maps team in Zurich for almost 15 years.

Swiss cartography: tradition over innovation

When Endoxon was acquired, Widmann could hardly believe that Google was willing to spend so much money on a small company in the Alps to build its own map service. The then-CEO says he cannot disclose the exact figure but talks of several million Swiss francs. In Switzerland, no one had seen his potential; indeed, the fact that Widmann used aerial images to produce the maps had caused him trouble.

“In Switzerland we did not attract much sympathy from the federal authorities. They accused us of wanting to destroy the reputation of cartography,” says Widmann, who also recalls the company being taken to court.

But the entrepreneur doesn’t hold a grudge. Switzerland was so proud of its cartographic tradition that such a reaction was quite natural, he says. Swiss cartographers’ ability to meticulously reproduce the details of rocks and terrain, even in the high mountains, was renowned the world over. So much so that, from the 1960s, Switzerland was called upon to produce maps of Mount Denali, the highest mountain in North America, as well as the Grand Canyon and Mount Everest.

>> VIDEO: Switzerland and its maps – a long history.

A special Swiss shading technique was able to give plasticity and a three-dimensional feel to rocks on a map.

“The Swiss representation of rocks and mountains was so immense that anyone reading the maps could understand them intuitively,” says historian Felix Frey, who works for the Federal Office of Topography (swisstopo).

There’s also a bit of Google in Swiss maps

For almost two hundred years, swisstopo has been an institution in the field of cartography. Its founder, Henri Dufour – for whom Switzerland’s highest mountain peak is named – played a key role in the development of modern maps, producing the first detailed map of the Swiss Confederation in the mid-19th century.

>> The first 1:100,000 topographic map of Switzerland, produced under the direction of Henri Dufour between 1845 and 1864.

Google recognises the importance of this contribution and makes no secret of its Swiss roots.

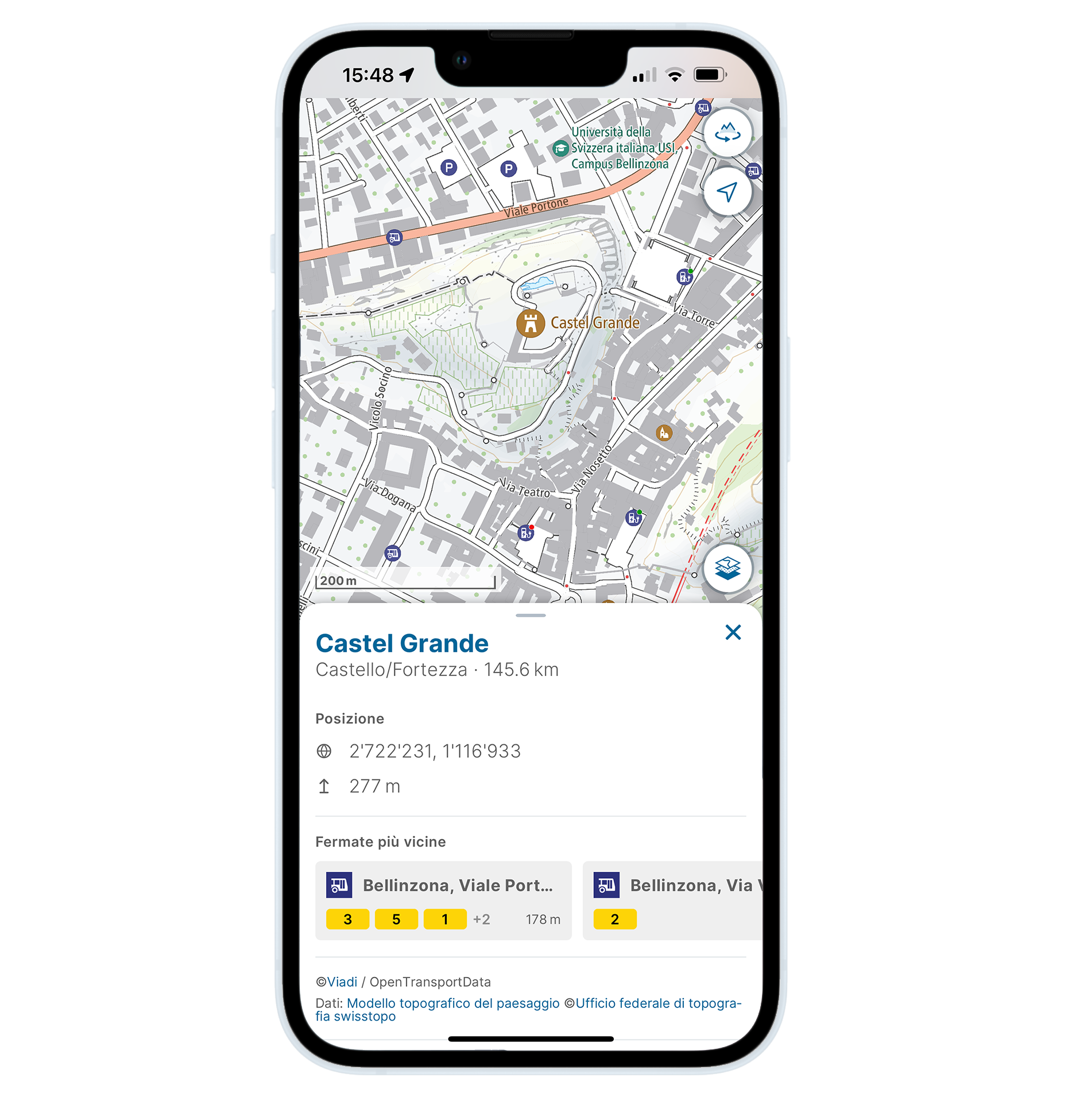

But today it’s more Google that influences swisstopo than the other way around, says Christoph Streit, head of cartography at swisstopo. Like Google’s maps, swisstopo’s are increasingly focused on interactivity, integrating information such as public transport timetables.

“Interactive cartography did not originate in national mapping agencies, but in IT companies like Google or Apple,” says Streit. For institutions like swisstopo, clicking on a map to get additional information is not the primary goal; the maps and their accurate visualisation of the topography remain in focus, Streit says. “For Google, on the other hand, maps are part of a business model based on user interaction.” Google users are probably less interested in studying a map or a territory, says Streit, but would instead like to know if a restaurant is open or whether there is a traffic jam.

This is why Google Maps works better in economically attractive urban areas than in rural ones. Swisstopo, with its public mandate, produces equally high-quality geodata and maps for all locations, regardless of commercial interest, says Streit.

“We do not want to and cannot compete with Google. We offer different services with different objectives,” he says.

Maps serving Google’s business

Thanks to digitisation, maps are more present in people’s lives than ever before. And Google takes full advantage of this. “Google does not consistently show what exists and is of interest to users but rather what is good for its business,” and it uses people’s data for this purpose, says Lorenz Hurni, director of the Institute of Cartography and Geoinformation at the federal technology institute ETH Zurich. Aerial images also make Google’s maps more ambiguous because not all geographic objects are clearly defined, for example when they are obscured by obstacles such as trees or poles, Hurni explains.

Google is so dominant that it is almost impossible for other companies to compete. This creates a monopoly-like situation, says Simon Poole of OpenStreetMap, considered the ‘Wikipedia’ of map data. “Google has combined its dominance as a search engine and as a geographic internet service. This is dangerous,” says Poole. The fact that Google collects so much information on users and can track and record their movements makes it particularly scary, Poole says.

Widmann is not worried that the original mapping project has evolved into a business model that some deem dangerous. He says he knows how much Google cares about user interests and privacy. The entrepreneur is more concerned about other players in the market that are catching up fast and do not meet the same standards. In his view, Google is successful because it offers a real model of the world. “I could no longer live without Google Maps,” says the entrepreneur who seems very attached to the company that changed his life. He is not alone.

Widmann is now an investor. Even though he no longer works for Google, he still has a nose for good ideas. He believes the challenge in the coming decades will be to create super-accurate, high-resolution maps around the world to be integrated into the systems of self-driving cars, he says. “This will be the next big innovation.”

Edited by Sabrina Weiss and Veronica De Vore

This article was corrected on April 23 to clarify ownership of the company Endoxon. Samuel Widmann joined the company in 2001 as head of new technology and later became CEO. The founders were Stefan and Bruno Muff.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.