Swiss entrepreneurs revive a Russian tradition

The Swiss have a long history of emigrating to Russia, contributing their skills as artists, teachers and farmers and making a good living for themselves.

After the Russian revolution of 1917 most of those who could do so returned home, but since the end of the Cold War at the beginning of the 1990s the Swiss have started to move back.

Relations between Switzerland and Russia have rarely been better than they are now: the Russian president, Dmitri Medvedev, who arrives in Switzerland on Monday is the first Russian head of state ever to pay a state visit.

Restaurateur and art collector Dolf Michel says chance brought him to Moscow. He first came in 1990, as part of a catering delegation for the Kremlin Cup tennis tournament.

He was then asked by a Swiss firm to open seven restaurants in the Russian capital, but in 2000 he got the chance to take over the historic Café des Artistes, in the very heart of town.

It could hardly be better situated: the most prestigious theatres and five-star hotels all around, and a back entrance to the Russian parliament building. And Michel could hardly be better suited to run it: an art lover himself, he restored its early 20th century decoration and ambiance, and uses part of it for art exhibitions.

Catering for the stars

Added to that, outstanding cuisine – French based “with a Russian touch”, as he described it to swissinfo.ch – with all the ingredients air freighted from abroad. No wonder that “everyone who is anyone” eats at his restaurant. Royalty, presidents, Hollywood stars, Russian showbiz personalities all figure in his guestbook.

As for the twin problems that are the bane of business, the mafia and bureaucracy, Michel shrugs them off.

“I never had problems with the mafia. I had good connections because of the Kremlin Cup. Of course I benefitted from these connections – not directly, but they were always there,” he told swissinfo.ch.

As for bureaucracy, he thought it was a nightmare – until he started trying to open a restaurant in Berlin.

“I’ll never complain about Russian bureaucracy again, now that I know what the Germans are like,” he smiled.

Teaching

Walter Denz has been in Russia almost as long as Michel, but he came for very different reasons and his success is in a very different field.

As a student of politics and international relations in the 1980s, he was interested in the changes occurring in eastern Europe, and keen to see for himself what was happening.

“We thought we would like to be part of history. It was an exciting time,” he explained.

He and his partner decided to move to Russia in 1991 – the last year of the Soviet Union. They had to set up a business simply to survive. The area they chose was perhaps not self-evident: a language school, teaching Russian to foreigners.

But the Liden & Denz Language Centres have proved highly successful, with about 2,000 pupils taking courses in Moscow and Petersburg every year.

Denz also has a travel business, setting up tours for Russians to Switzerland and other European countries.

Chaos and excitement

Russians look back on the 1990s as years of chaos, but Denz has a different take.

“It might have been dangerous and a bit unpleasant at times, but it was also a very exciting period, where you had a free press and political streams fighting for influence. I have quite fond memories,” he said.

Given all he had invested, he felt he couldn’t pull out whatever happened. There were plenty of problems – but he accepts that not all were inevitable. He and his partner made mistakes too.

And as for the mafia, a small business like his is “under the radar” for them, he believes. Corruption he describes as “one of the foundations of the whole system”, but his advice is never to take shortcuts with the legal system, to avoid the danger of blackmail.

A good network is essential for anyone who wants to do business in Russia, but is not easy for foreigners to build up, not least because they have little to offer in exchange for help they are given.

Fortunately, many Russians are willing to help simply because they are interested and “really nice.” And people like Denz now have an extra advantage: many Russians are amazed that a foreigner stuck it out through the chaos of the 1990s.

“You gain genuine respect simply by staying for a long time. That makes it easier to maintain such a network.”

Farming

Far from the hustle and bustle of Moscow and St Petersburg Hans-Peter Michel represents another type of Swiss emigrant. He is a relative newcomer, having arrived in 2004, inspired by an article he read in a farming magazine which said there was land available and Russia was looking for farmers.

He gave up the 16 hectare farm he had inherited from his father in the Bernese Oberland, with its 30-strong herd of cattle, and together with two Swiss partners he bought Schweizer Milch (Swiss Milk), in the Kaluga region south of Moscow.

He is now its general director, overseeing 34 employees on a 700ha holding with about 550 head of cattle.

The business pasteurises the milk from its cows and distributes it locally.

The Kaluga region is active in attracting foreign entrepreneurs, offering special conditions and smoothing the bureaucracy, to boost its own economy. And Michel’s Schweizer Milch has done just that. Other enterprises, including an agricultural machinery repair shop, have been set up in its wake.

But the Swiss Foundation in Kaluga also helped: it provides advantageous loans to small and medium-sized businesses, which means that there was already a helpful Swiss network in existence when he arrived.

Michel now has a Russian wife and two children. Like his two compatriots, he is in Russia for the long term.

“As long as I am still motivated and continue to like it, I shall stay here,” he said.

Julia Slater in Moscow, St Petersburg and Kaluga, swissinfo.ch

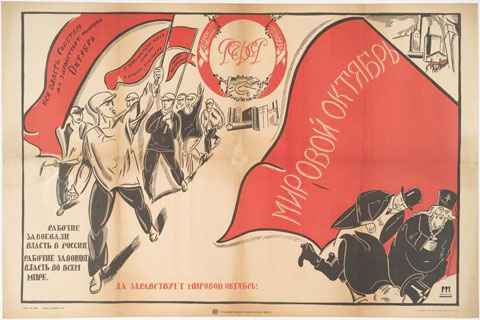

Russia started opening up to the West towards the end of the 17th century.

One of the earliest and most influential Swiss to move there was François le Fort of Geneva, who became a close friend of Peter the Great, and encouraged his westernising plans.

A century later another influential Swiss was Frédéric César de la Harpe, tutor to the future Tsar Alexander I – who failed to introduce many reforms, but who played a key role in Switzerland’s fate after the Napoleonic wars.

Many of the first architects of St Petersburg – founded in 1703 – were Swiss, and a number of eminent scholars in the early days of the Academy of Science also came from Switzerland.

In the 19th century Swiss farmers and confectioners were among those who moved to Russia in search of a better life.

When the Russian Revolution broke out in 1917, there were about 8,000 Swiss living in Russia, about half of them businessmen and teachers.

Most lived in St Petersburg and Moscow, with another concentration in the southern port city of Odessa.

It has been estimated that between 1700 and 1917 between 50-60,000 Swiss lived in Russia.

According to the Swiss embassy in Moscow, 701 Swiss citizens were registered as resident in Russia in 2008.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.