The challenges of research in treeless landscapes

The temperatures on Svalbard are too low and the soil too shallow for trees to grow. In this type of biome called tundra, dwarf-shrubs, mosses and lichen prevail, with some specialised small herbs and grasses.

With a growing season of only six to eight weeks, the landscape changes quite rapidly. When we arrived in early July, during peak tundra season, the landscape was a rich dark green and flowers were in bloom. Some researchers in our group needed to return to Svalbard at the end of August to collect ripe plant seeds for our plant competition experiment back in Zurich. By this time, autumn had already begun, mountain tops were covered in snow and the tundra had started to turn wonderful shades of orange and red. We were surprised to see how fast the plants changed and how much wetter the soil was.

2MB – that was the daily amount of data our original bloggers from the Antarctic were allowed to send us via satellite about their research on microplastics. Data transmission is also limited this summer for Lena Bakker, Sigrid Trier Kjaer and Jana Rüthers (left to right), three other PhD students at the ETH Zurich who are heading north to the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard to investigate Arctic greening, a process initiated by global warming and driven locally by soil chemistry, thickness and age.

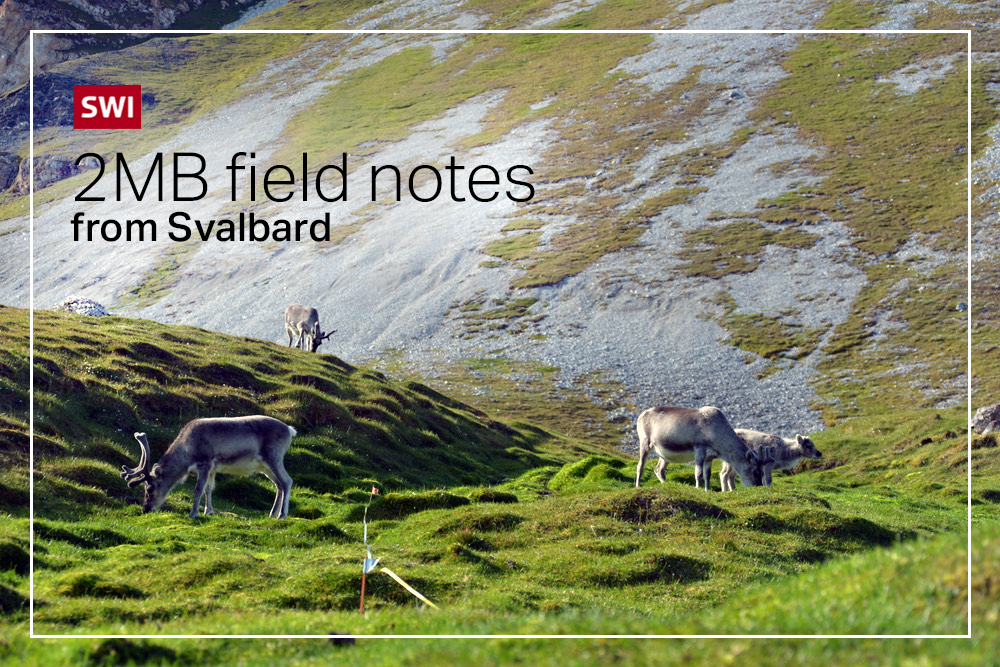

One challenge we experienced in the vast tundra was estimating distances and sizes. Here in Switzerland one can simply look at a nearby tree and use it as a general reference for sizes. We seem to be doing this more or less subconsciously. But without trees or even bushes in the tundra this reference is lost. The many scattered rocks were a very poor substitute, also because they often looked a bit too much like polar bears (the whiter ones especially). This means that all the mountains, rivers, rocks and meadows seemed both large and small at the same time. It also meant that guessing the hiking times to interesting plots that we found from the boat while scouting did not really reflect reality most of the time. This happened especially along the coastline at Festningen, where what we thought would be a 20- or 30-minute hike ended up taking an hour. Luckily this phenomenon also kept the tundra fascinating, so that we often did not mind hiking a bit longer.

Speaking of polar bears, part of our safety training at the shooting range included guessing distances to random objects that were scattered in the stony tundra. That should have helped us assess the danger when a polar bear came into view. The closer a bear came, the more dangerous it could become. We would have needed to deter or distract the animal, for example, by gathering our group and slowly moving away, by screaming and making a lot of noise, or by shooting a flare gun into the sky to scare it away.

When we practiced this in our training, we quickly understood that it takes a lot of experience and a good sense of the terrain to be able to correctly assess the distances and danger in this treeless landscape. Luckily, a trained bear guard accompanied us during our fieldwork. Once while we were out she saw a polar bear about 2km away, and we all had to return to the boat.

Adventdalen, a 30-kilometre-long valley that stretches towards Longyearbyen, was amongst the first sites we visited after our arrival in Svalbard. The tundra is very special for us, because this is where we started to test out our planned methods and work routine. After long hours in the field, our work continued in the “laboratories”, or in this case, the small areas we set up in front of our guesthouse and in its breakfast room. Here, we preserved and processed the plant and soil samples we collected for later microbial analyses in Zurich.

And as the sun never set, we had a lot of time in the evenings (or sometimes even nights) to get everything done, and to keep on admiring the omnipresent tundra and its inhabitants.

Scroll down to read earlier entries from Lena, Sigrid and Jana. To receive future editions of this blog in your inbox, sign up for our science newsletter by putting your e-mail address in the field below.

More

2MB field notes from Svalbard

More

Climate change, even in the remote Arctic?

More

The links between human settlements and Arctic greening

More

Droppings of Arctic seabirds enrich the environment

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.