Why today’s Swiss waterways are fit for swimming

Up until the 1950s, waste was dumped directly into Swiss rivers and lakes, resulting in dying fish, bad smells and swimming bans. Much has changed since then. The entire population is connected to sewage treatment plants but new challenges are on the horizon.

Today, clean streams, rivers and lakes are pretty much the norm in Switzerland, and for many people the country is considered a model for its water quality. It is hard to believe that in Swiss lakes, where children are currently splashing around in the hot weather, bathing was once banned.

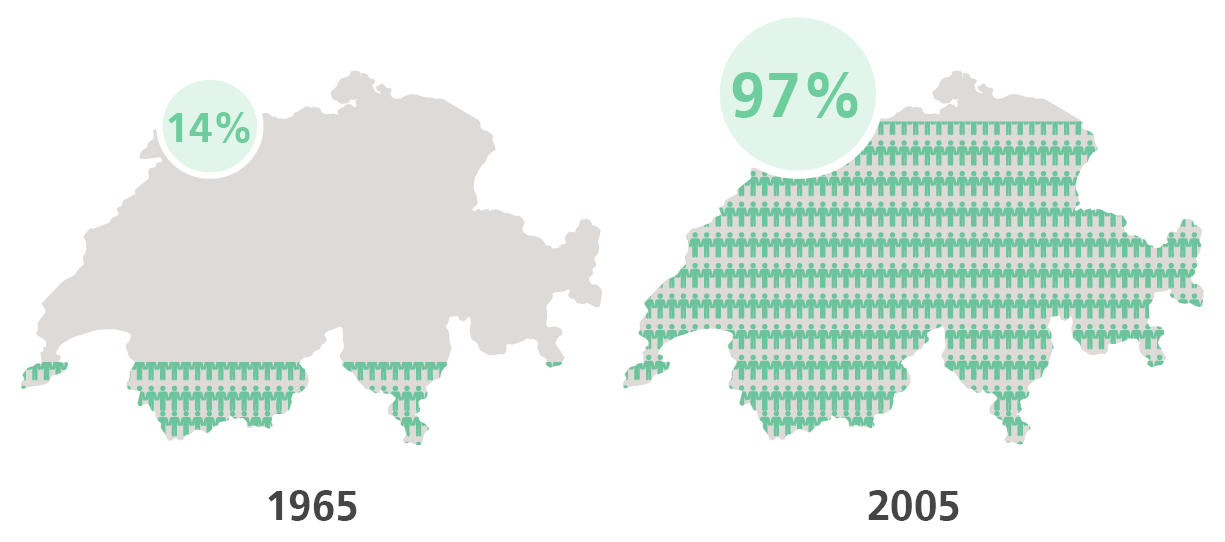

However, up until the 1960s only about 15% of the Swiss population was connected to a wastewater treatment plant. Wastewater often flowed directly into rivers and lakes. Even commercial and industrial wastewater containing toxic substances used to go untreated into the waters.

As a child in the 1970s, Michael Schärer, head of the Water Body Protection Section at the Federal Office for the Environment, used to watch so-called ‘sea cow’ boats at work removing large amounts of algae from a lake.

Schärer told Swiss public radio, SRF, that during his parents’ time, people would sometimes fall ill and suffer from diarrhoea if they accidently swallowed water while swimming in a lake. In many places, signs used to warn swimmers to “bathe at your own risk”.

More

Switzerland is a ‘wastewater treatment pioneer’

The public puts on the pressure

Water pollution used to be very visible: mountains of foam in polluted streams, pieces of old toilet paper scattered on shorelines, carpets of algae, and dead fish floating on the water’s surface. You could also smell it.

In 1963, a typhus epidemic broke out in the mountain resort of Zermatt. Three people died and over 450 fell sick. The federal government and cantons then decided to subsidise the construction of wastewater systems in local communes.

The driving force for water protection in Switzerland was often the general public, and their growing environmental awareness. In 1967, the public demanded a policy change with the “Protection of Waters against Pollution” people’s initiative. In 1971, the treatment of wastewater was finally written into Swiss law.

By 2005, 97% of the population was connected to a central sewage treatment plant. Today, the sewer network stretches over 130,000 kilometres, and there are 800 sewage treatment plants.

This success did not come cheap. The expansion of the infrastructure – sewer systems, wastewater treatment plants and other wastewater disposal facilities – cost a whopping CHF50 billion. The federal government contributed CHF5.3 billion to the implementation of the long-term project. This year it is paying out the last CHF10 million to the communes.

Success story?

In recent years, Switzerland has done a great deal to protect and clean up its waters. Schärer describes it as a Swiss “success story”.

He says the public are privileged to be able to swim in city centres. “Many tourists are amazed at this,” he declared. And it is an “incredible luxury”, he goes on, that in Switzerland you can drink high-quality water straight from the tap.

However, there are still challenges ahead. Micropollutants such as drug residues, pesticides, chemicals and hormones are harming animals and plants. But sewage treatment plants cannot filter them out. The products can lead to organ damage and sterility in fish, for example.

Switzerland has committed to remove micropollutants from wastewater by 2040. A government programme aims to equip 100 wastewater plants with anti-micropollutant technologies that can each filter out 80% of all micropollutants. But the project comes at a high cost: around CHF1 billion.

In Switzerland, cost-covering principle of ‘polluter pays’ is applied to wastewater fees. The communes and wastewater associations charge monthly fees. These vary from commune to commune of around CHF20-70 per four-person household, depending on the type of wastewater treatment facility.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.