Suicide rate down as people learn to seek help

From being one of Europe’s suicide black spots, the Swiss suicide rate has declined over the past two decades to lie close to the European average. The change has largely been attributed to greater readiness to seek help for mental illness.

Between 1991 and 2011 the Swiss suicide rate fell from 20.7 per 100,000 population to 11.2 per 100,000 – a period which also saw a dramatic increase in antidepressant use across Europe.

A London School of Economics study published in the online journal PLOS ONE earlier this year found that antidepressant use among 29 European countries went up an average of 20 per cent every year between the years 1995 and 2009.

According to sociologist Vladeta Ajdacic-Gross of the Psychiatric University Hospital in Zurich, there is a more significant phenomenon behind the increased prescription of anti-depressants.

“For doctors to prescribe medication, the sufferer must go to the doctor. It’s not only the behaviour of the medical community that has changed but people’s behaviour in general,” Ajdacic-Gross told swissinfo.ch.

People have learned to think in psychological terms and understand that there are underlying reasons for their problems. “We have arguments to explain our psychological problems and we’re more willing to talk about them. We have found acceptable metaphors for depression, such as burnout.”

“That, in my opinion, is the most important factor influencing the suicide rate,” he added.

More

Suicide attempts in one city

At risk

Anita Riecher-Rössler of Basel Psychiatric University Clinics, who has carried out extensive research into suicide attempts, agrees that people with psychological and psychiatric problems are more likely to seek help nowadays.

However, she believes there is not enough targeted prevention work and points out that, with 15,000 to 25,000 suicide attempts per year and 1,300 deaths, suicide still is a major public health problem in Switzerland and is associated with severe emotional suffering.

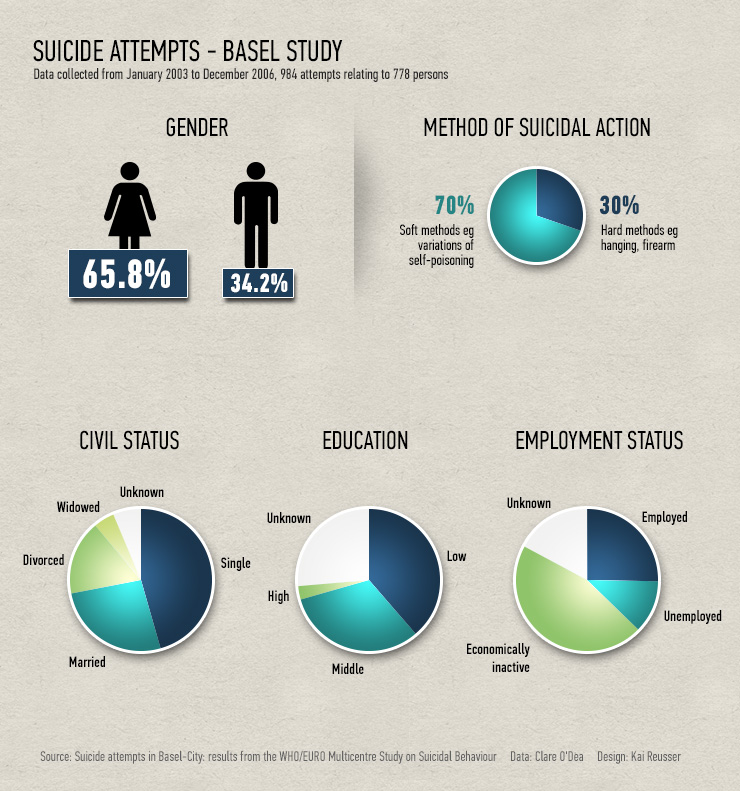

Riecher-Rössleris is the senior author of a recent study of suicide attempts in Basel which throws light on who is most at risk (see infographic).

The study, which appeared in Swiss Medical Weekly, offers the first published representative data of a Swiss canton. It concluded that specific prevention efforts “should focus on persons at risk who were characterised as being younger, foreign, living alone and being unemployed”.

Researchers identified two peak age groups for suicide attempts: for men, 30 to 34 years followed by 20 to 24 years, and for women, 20 to 24 followed by 25 to 29.

The highest risk group of all includes those who have already attempted suicide, more than half of whom will make repeat attempts, Riecher-Rössler told swissinfo.ch

“As shown in our study, 98 per cent of the patients had a psychiatric diagnosis to start with. All of these people need very intensive aftercare, not only to prevent a repeated suicide attempt but also to treat the psychiatric disorder,” she noted.

One in ten people will attempt suicide at some point in their lives and 50 per cent admit to having considered suicide at one time.

The suicide rate is higher among men than women and higher among older people than young people; the reverse is true for attempted suicide and suicidal thoughts.

60 to 90 per cent of suicidal patients fulfil the diagnostic criteria for a psychiatric illness, mostly depression; a transitory crisis is often the trigger of suicidal behaviour among young people.

Source: FSSZ http://fssz.ch/zahlen-fakten/

Free will

With Switzerland’s exemplary health care system, surely this care is available? In theory yes, according to Riecher-Rössler – the care is offered, but people still slip through the cracks. Because of a strong emphasis in Switzerland on patient autonomy, “aftercare just stops when patients don’t turn up for appointments”.

Barbara Weil of the umbrella suicide prevention organisation Ipsilon believes the emphasis on patient autonomy is problematic when it comes to mental illness.

“In the Swiss mentality you have the opinion that I can do with my life and my body what I want to. This has an influence on how suicide problems are viewed in society. People think the act has been well thought through, that it’s an expression of free will and you can’t do anything about it, which of course is not the case,” Weil said.

Key elements contributing to suicide prevention include the restriction of means of committing suicide and tackling the taboo of mental illness, Weil told swissinfo.ch.

“It is also important to raise awareness among professionals, such as general practitioners and teachers, who come into contact with people who might be depressed or suicidal,” Weil said.

by Jeannie Wurz, swissinfo.ch

An army-related restriction in access to guns in 2003 led to an “enduring decrease” in Switzerland’s general suicide rate, Bern researchers found in July 2013.

“Change in suicide rates in Switzerland before and after firearm restriction resulting from the 2003 ‘Army XXI’ reform”, published in The American Journal of Psychiatry, looked at suicide rates of 18-43-year-old men in Switzerland before and after the 2003 reforms. The reforms cut the number of soldiers from 400,000 to 200,000 and reduced the age of discharge from 43 to 33.

“We know that the availability of methods plays a major role in suicide, and especially for methods that are used impulsively,” the study’s lead author, Thomas Reisch, told swissinfo.ch. “And that’s particularly so for firearms – you can expect that when the gun is no longer available, there will be a resulting reduction in suicides.”

Because Swiss conscripts are required to keep their weapons at home between training courses and during service on weekends, the reforms led to fewer men with access to weapons and less opportunity to practice using them, said Reisch.

The study found a reduction in the overall suicide rate and the firearm suicide rate in 18- to 43-year-old men after the reform. There were no statistically significant changes in the number of suicides in a comparison group of women aged 18 to 43 or a comparison group of men aged 44-53 over the same period.

In the study group “it appeared that there was a small proportion – 22 per cent – who potentially turned to another method” to commit suicide when access to firearms was restricted, said Reisch.

Room for improvement?

People in Switzerland are still learning to seek help, according to Ajdacic-Gross. “There has been significant progress in taking away the stigma but there is lots of room for improvement. There is a high proportion of people who do not seek help for depression – one in two.”

It may also be a generational issue. In the Basel study, a second peak in suicide risk was observed in the elderly, most notably among men aged 85 to 89 and women aged 60 to 64.

“We are so focused on youth suicide prevention that we forget that the suicide rate skyrockets in elderly people. This is a huge problem. Because they are older, people say they’ve had their lives so it’s okay, which it’s not,” Weil said.

“The early detection of depression and suicidality in elderly people is needed just as much as for youngsters,” she added.

Ajdacic-Gross believes a much greater impact could be made on the suicide rate with a national targeted prevention programme. Suicide prevention activity is currently left to the 26 cantons and charities.

“It does not make sense to have national programmes for road accident prevention and not to have a corresponding programme for suicide,” he said.

The number of road accident fatalities in 2009 was down to one fifth of the 1970 level despite increased traffic volume and continuous population growth.

“What we have achieved in road deaths, we could also achieve in suicide,” he added.

One in five Swiss suicides are assisted suicides, mainly facilitated by two organisations – Dignitas and Exit.

Swiss law tolerates assisted suicide when the act is committed by the patient and the helper has no direct interest.

Assisted suicide figures were included by the Federal Statistics Office in the national suicide rate from 1999 (63 cases) to 2008 (297 cases).

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.