The Swiss vote more than any other country

Swiss citizens have more chances to express their opinions at the ballot box than anyone else in the world, thanks to their extensive system of direct democracy.

In most democracies, citizens only turn out to vote for elections – presidential, parliamentary or local. It is the representatives they choose on these occasions who take political decisions on their behalf. That’s indirect democracy.

In an indirect democracy it is unusual for citizens to be asked to vote on specific issues. One exception in Europe in recent years has been the decision by a few countries to give citizens a say on European integration.

The situation is quite different in Switzerland. Parliamentary elections are only held every four years, but the Swiss get the chance to vote on particular issues three or four times a year.

Some of the issues they are asked to decide on are at federal level: citizens all over the country vote on the same thing. But they are also usually asked to vote on issues relevant to their own canton and even their own commune as well.

Recent cantonal votes have included anti-hooligan measures approved in Zurich, or a proposal to bid for the 2022 Winter Olympics, turned down in Graubünden which would have hosted them. Issues that are turned down at national level may be subsequently voted on by the individual cantons. Thus many cantons are likely to hold their own vote on the provision of child care for all, rejected in March 2013 when it failed to get the support of a majority of cantons.

At the communal level votes are often to do with the funding of infrastructure, perhaps a new museum, or extending a local bus route. In recent times, tiny communes have been merging in order to preserve the level of services they can offer, something that can only happen with the approval of the inhabitants.

Unique rights

Although some other countries or regions of the world also have direct democracy, none use it in exactly the same way as the Swiss.

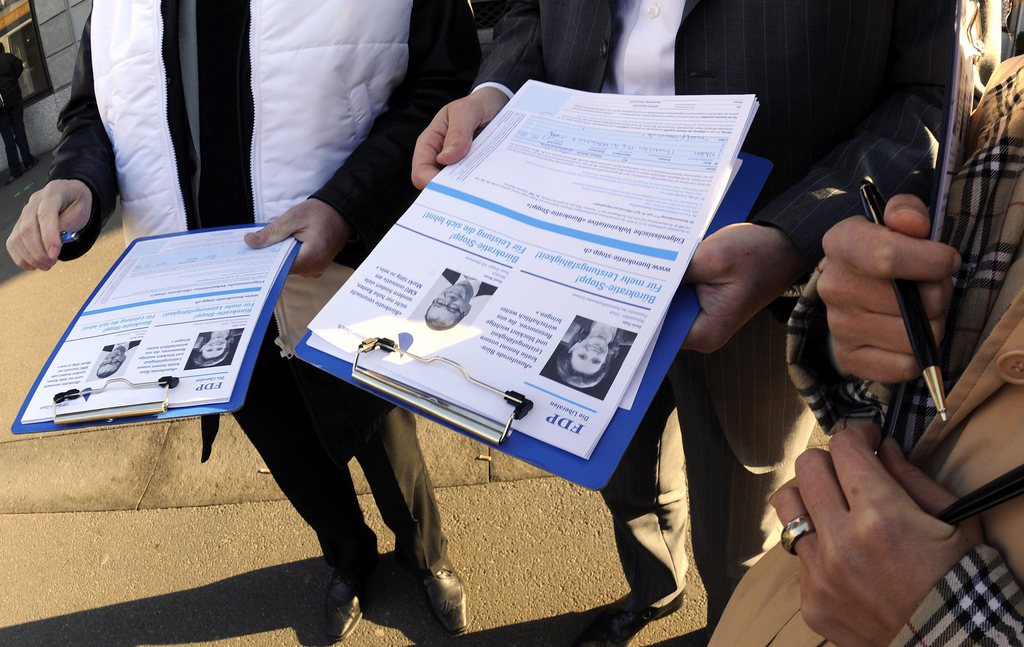

Swiss citizens can propose legislation of their own, by putting forward what is known as a people’s initiative, or they can thwart legislation already approved by parliament, by calling a referendum.

Initiatives enable citizens to put forward amendments to existing articles in the constitution or to propose new ones. To call a nationwide vote, supporters have to collect 100,000 signatures and submit them to the Federal Chancellery within 18 months of the official launch of the campaign.

The signatures are checked, to make sure, for example, that no-one has signed twice and that all signatories are Swiss citizens with the right to vote.

But before it is put to the vote it is carefully examined by the government and parliament. Discussion can go on for several years if the issue is particularly divisive.

Political or social groups often submit issues to the people which would be unlikely to find a parliamentary majority. Often it is leftwing groups which call votes on social and economic issues, while the rightwing tends to submit ideas on national identity and foreigners.

But any group or private citizen has the right to propose an initiative. Most of these are turned down, but in March 2013 the so-called Minder initiative against “fat cat” salaries, put forward by businessman and independent member of parliament Thomas Minder, gained over two thirds of the popular vote and was supported by all the cantons.

While the initiative can be seen as an accelerator, the referendum acts like a brake. It’s used to cancel legislation that has already been approved by parliament.

For a referendum, opponents have to collect at least 50,000 signatures and submit them to the Federal Chancellery within 100 days of the law being published. For the referendum to pass, it requires only a majority of all the voters.

There is a second kind of referendum, the obligatory one: when parliament has approved legislation that changes the constitution in any way, the people have to be given their say. This requires a so-called double majority – not only a majority of voters, but also a majority of the cantons have to accept the change.

Such modifications are by no means unusual, since the constitution includes a number of articles that are likely to be changed fairly frequently, such as the rate of Value AddedTax.

Criticism

The Swiss are proud of their system of direct democracy, but this does not stop some of them finding fault with some of its aspects. One frequent criticism is that there are too many votes, and that they are too complicated. Turnout varies widely, depending on the issue, but generally hovers around only 40 per cent.

But more seriously, some people ask whether it is right for citizens to have the chance to vote on every issue, some of which are very complex, and provoke passionate debates.

In a controversial vote in 2009, for example, two-thirds of voters came out in favour of a change to the constitution by approving an initiative to ban the construction of minarets in Switzerland.

A number of appeals were subsequently submitted to the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg, claiming that the ban violated the human rights of Muslims in Switzerland. The appeals were turned down on the grounds that the appellants were not directly affected since they were not planning to build a minaret themselves.

The Swiss government can only prevent voting on an initiative if it violates “peremptory norms”, in other words norms which are obligatory under international law – such things as the prohibition of crimes against humanity, genocide, slavery and torture. Although it strongly opposed the minaret initiative, its hands were tied.

Promoting discussion

Whatever lessons may or may not be learned from the minaret vote, it is generally agreed that a major bonus of the Swiss system is that it enables issues to be discussed that might otherwise be ignored.

Thanks to an initiative some 20 years ago, the Swiss had the chance to debate whether the army should be abolished – not a subject ever likely to have been brought up in parliament.

More recently, in 2003, an initiative calling for better rights for the disabled was rejected, but some of its proposals were incorporated into legislation which came into force in 2004.

Many commentators see another important advantage of the direct democracy system as helping to sustain the delicate balance between the different groups in Swiss society.

The double majority rule was introduced to prevent the smaller cantons being steam-rollered by the bigger ones, for example. But a nationwide initiative that fails for this reason can always be proposed subsequently at the level of individual cantons.

Thus the opposition in March 2013 of conservative rural voters to an initiative to improve childcare facilities does not mean that women in cities who want to go out to work will necessarily find themselves tied to their homes. A cantonal vote on the same issue would have a good chance of success in more urban cantons.

Switzerland prides itself on its talent for compromise. Both government and parliament are forced to look for the broadest possible consensus when framing new legislation, in order to avoid defeat in a referendum.

(with input from Olivier Pauchard)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.