Why Switzerland welcomed Prague Spring refugees

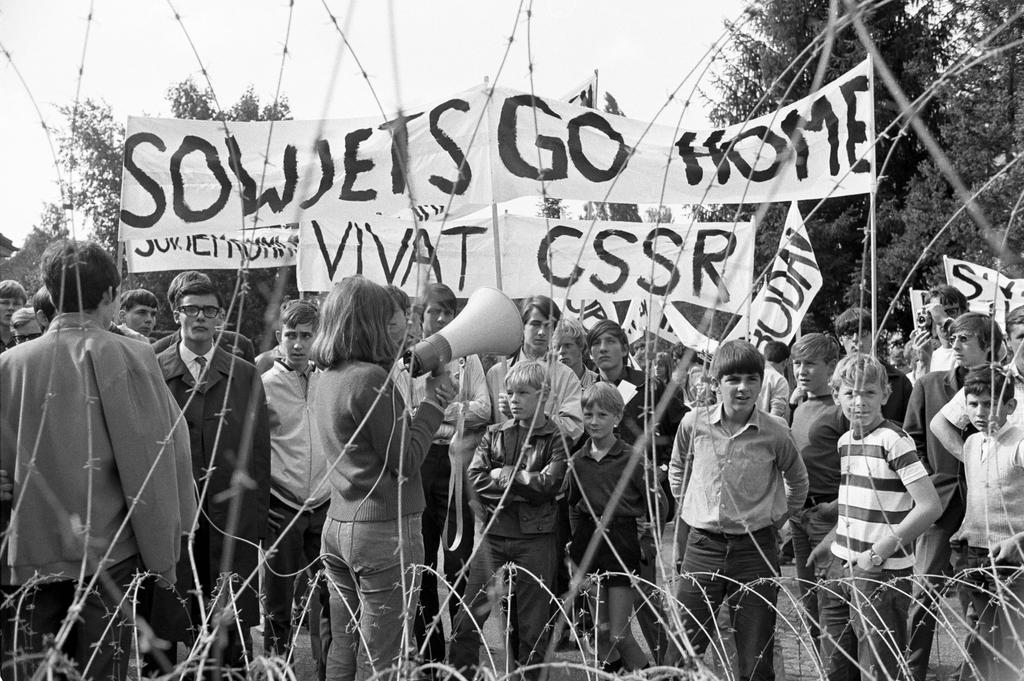

After Warsaw Pact tanks rolled into Czechoslovakia on the night of August 20, 1968 to crush the Prague Spring movement, many Czechs and Slovaks found refuge in Switzerland.

Irena Brežná was in France at an international student camp, “laughing and happy to be able to travel and visit a capitalist country”. Political liberalisation brought about after the election of Alexander Dubček to head the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia in January 1968 meant that “people could again read newspapers and discuss openly”, she explains.

But after half a million troops from Soviet-controlled states invaded the country to suppress reforms, killing 137 civilians, the 18-year-old Slovak’s mother called to say that she should not return home and that both parents, like many others, would emigrate.

“It was the greatest shock in my life. We felt betrayed by the system. I couldn’t go back. If I returned, I would be unable to study, as I would be seen as the daughter of the state’s enemies”.

After initial plans to migrate with her mother to Canada, the two instead applied for Swiss asylum, before being joined by her father who had first gone to Germany.

“I felt that everything that I had known before was gone,” says Brežná, a writer and specialist in Slavic Studies. “It was a desperate feeling that there was no way back. It was a shock to be a refugee. I only felt my sadness”.

Adapting to Switzerland was not easy. She found Swiss society conservative and women considered less equal in studies and work than what she had known at home. She also felt “humiliated” for not being able to express herself fully in German but was committed to learning the language.

Her story – the inspiration for her books External link– is just one of many Czechs and Slovaks who migrated to Switzerland could tell.

Twice a migrant?

Jiří Růžička also emigrated to Switzerland in 1968, applying for asylum under an expedited process introduced by Switzerland following the invasion. A musician and composer, he settled in the capital, Bern, and worked at theatres throughout western Switzerland. In a catalogue External linkpublished for an exhibit that is taking place in the Czech Republic and Slovakia this year entitled “A Second Life” about migrants from Czechoslovakia to Switzerland after 1968, Růžička recounts how the communist regime hadn’t allowed him to work freely because of his family’s “bourgeois” property-owning background. The exhibitExternal link was conceived and produced by the Swiss embassy in Prague.

His story of building a new life was also told in a short filmExternal link (in German and Czech) directed by Fiona Ziegler, a Swiss cinematographer, for the exhibit, with the support of Switzerland.

But after the Velvet Revolution in 1989 brought an end to the communist regime, Růžička returned to Prague. “At the beginning it wasn’t easy at all. It changed a lot since I left, but there were still the same people in the state offices as before the Velvet Revolution.” He said that while he is convinced that emigration had saved his life, authorities in Prague after 1989 called him a “damned immigrant”.

Now 77 years old, Růžička – like some of an estimated 6,000 others who returned – describes his life in separate phases, before emigration, life in Switzerland, and his return.

More

When the Prague Spring came to Switzerland

According to the United Nations, a migrant on average spends approximately 30 years away before returning home.

Emigrant country’s closed doors

The filmmaker, Fiona Ziegler, admits that the exhibit was intended to show the public that while Czechoslovakia had been a source of migration, the two separate countries that emerged after 1991 have welcomed hardly any refugees. Even those who had left years earlier were not welcome back.

But migration policies in the West have also shifted.

In 1968, when Switzerland opened its borders to Czech migrants, the world was at the height of the Cold War.

“We had a black and white vision of the world, of communism versus democracy, where we felt in the West that people living under communism were victims that had to be supported to allow them to have a free and idealistic life. It was very idealistic,” the Swiss filmmaker says.

In contrast, now “we are afraid of everything that comes from abroad. It’s very schematic.”

But that approach she says is much more pronounced now in today’s Czech Republic and Slovakia. “They do not accept anyone from outside and don’t realize that after Czechs needed help in the past from others, now they should help those in need from elsewhere”.

“Skilled” migrants

“The immigration policies toward Czechoslovakians were simply based on humanitarian grounds,” says Rolf Ott, deputy head of mission at the Swiss embassy in Prague, commenting on Switzerland’s migration policies at the time of the invasion.

He added that given the economic boom at the time, “Switzerland needed skilled labour”.

“A large number of these persons were well educated – students, academics and technicians – when they arrived in Switzerland.”

Like Jiří Dvořák. The neurology professor at the University of Zurich, senior consultant at the Schulthess Clinic and a former FIFA medical chief, was a second-year medical student when he came to Switzerland.

He told swissinfo.ch how on August 21, 1968, together with his parents whom he was visiting in Cuba, they were captured by Cuban and Russian officials, and loaded onto a plane without being told where it was going. The plane brought them back to Prague.

“It was a perfectly masterminded plan by the organization,” Dvořák remembers. “They were afraid that the Czechoslovakian citizens could cause trouble in Cuba”.

Three months later, after the last protests to the invasion were organised in the Czechoslovak capital, Dvořák realized there was no hope left for returning to earlier political reforms. He decided to leave on his own, with his parents’ approval, “even though they knew they would be heavily under pressure”.

“It was not very easy, but I think I made the right decision. I then broke all ties to my former country and started to plan my new life.”

He worked as a construction worker and gardener – which helped him learn German – before resuming his studies in medicine in Zurich.

Fairness and punctual

Frantisek Pojdl had already been working in Zurich as part of an exchange programme between public broadcasters when he requested asylum after the Soviet invasion.

Pojdl’s son Pavel, a commodities trader and a former professional ice hockey player for Geneva Servette who was 12 when he came to Switzerland, explained how his mother joined the family by escaping in a moving truck, wrapped in a carpet.

“I am grateful to my parents to have gone through the painful decision of leaving and of coming to Switzerland”.

He says arbitrary rules under communism that encouraged lying and cheating were the “modus operandi” at the time. “Rules made no sense under the communists, so people tried to beat them. And then when you come to Switzerland it was fairness and punctuality. Rules were to be obeyed.”

Existential

In “The Unbearable Lightness of Being”, Czech author Milan Kundera who migrated to France in 1975, recounts the moral and existential conflicts of a fictional couple that leaves Czechoslovakia to move to Geneva.

Kundera’s romantic depiction of migrants has been supplanted in recent years by the refugee crisis involving hundreds of thousands of migrants seeking asylum in a less-than-welcoming Europe. However, the inability to return for fear of persecution is a common thread.

“Nobody leaves his or her country and asks for asylum in another without being in a state of utter need and despair,” Dominik Furgler, Swiss ambassador to Prague, wrote in the prefix to the Second Life catalogue. “I truly hope that the exhibit… will encourage people to reflect on the controversial issue of migration in general.”

Dvořák, who has worked regularly for humanitarian missions in Africa, says that with much of migration now motivated by economic reasons more should be done to stimulate development at home.

For Brežná’s part, she is critical of the unwillingness of the Czech Republic, Slovakia and other former Soviet bloc countries to welcome refugees.

“I feel so good in Switzerland when I hear so many languages. In Slovakia most people don’t know any foreigners. Like before, they want to remain isolated.”

Refugees today

According to the International Organization for MigrationExternal link (IOM), more than 40 million people are estimated to be internally displaced within their own countries while more than 22 million have sought refuge abroad. The IOM says this “global displacement” is at a record high.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.