Zurich youngsters go on rampage against religious art

Hans Feer was carrying a heavy load on his cart through the city of Zurich on May 9, 1587. One chest weighed almost 300 kilogrammes; the two others required two strong men to carry them.

The chests came from the workshop of the Vorarlberg artist Heinrich Dieffolt, who had been commissioned to produce an altarpiece for the Catholic churches of Sursee and Merenschwand. As agreed, Dieffolt had delivered the chests to a warehouse in Zurich, where the cart driver had picked them up.

Feer, a Catholic, was somewhat uneasy about transporting saints and angels through the city where Reformers had banned all statues of saints from their churches. When a passer-by asked him what he was carrying, he responded curtly: “We’re taking coffins away. Don’t be afraid! No one else will die this year because we’re taking away all the dead.”

This historical account is part of a series of swissinfo.ch articles marking 500 years of the Reformation. The origin of the Reformation is generally considered to date back to the publication in Germany of the Martin Luther’s 95 Theses on October 31, 1517.

But when another passer-by asked him whether his load was valuable, he replied that it was “as precious as the remains of the dead of Zug”. Suddenly, an icy cloud descended. His off-the-cuff remark referred to a three-year-old dispute between Catholic Zug and Protestant Zurich, which had demonstrated how tense relations were between those who stuck to old beliefs and those who had adopted the new.

The people of Zug had begun digging up the remains of Zurich victims of the last War of Kappel. Fifty years after the battle, they wanted to move the bones to an ossuary, but the people of Zurich were convinced that the Catholics wanted to desecrate their dead. They had managed to ensure the bones were reinterred, but they had never forgotten or forgiven the affront. It was little wonder that they suspected the Catholic cart driver of mocking their dead heroes “with scornful, offensive words”.

Hans Feer was clearly disturbed by the hostility towards him. What else could have caused him to shoo three Zurich women out of the way with the words, “Don’t come too close to my cart or you will die!”

A step too far

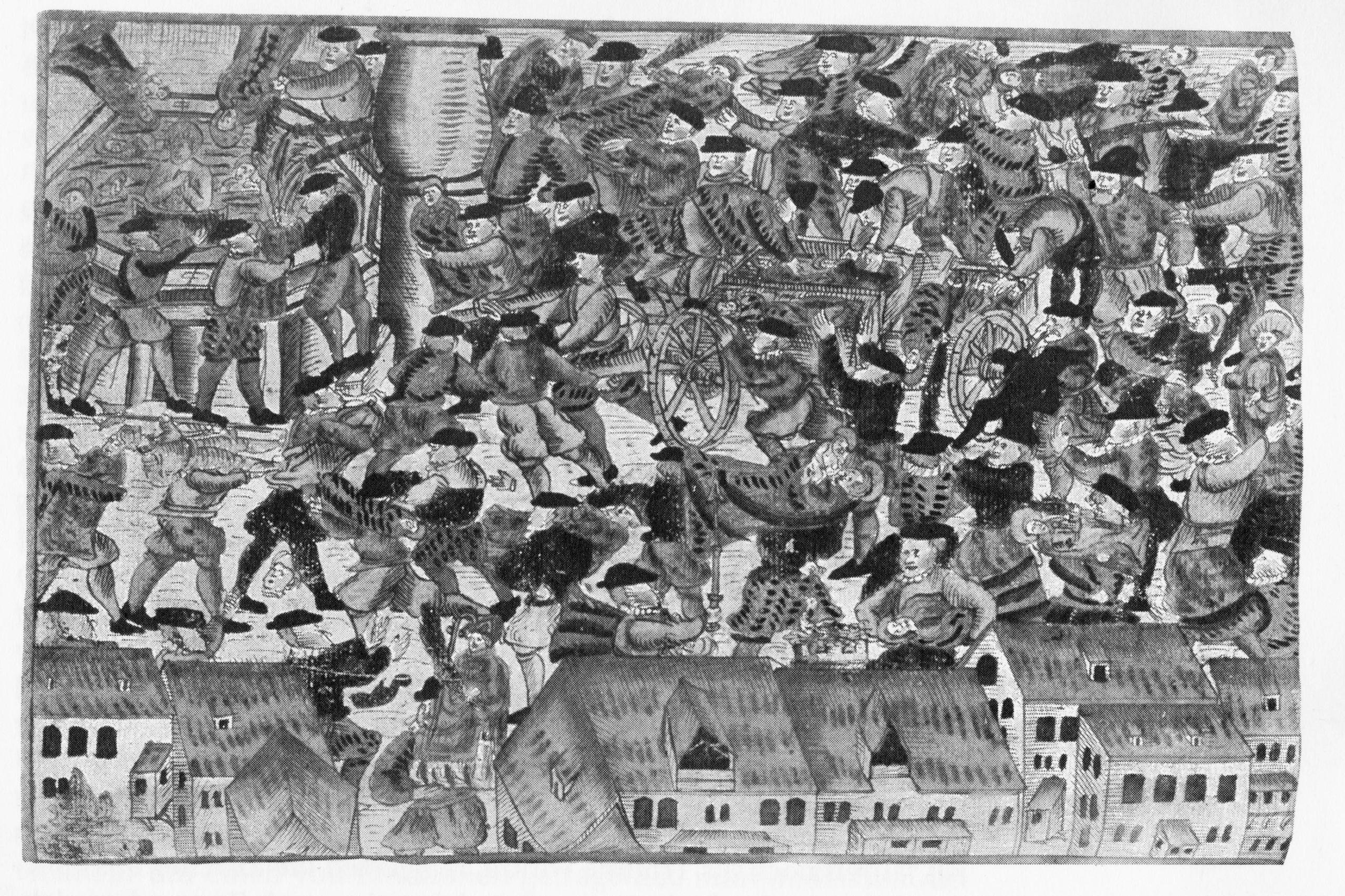

The threat was a step too far for some people. Angry citizens barred his way and six young men jumped on to the cart’s loading platform to inspect his mysterious cargo. They broke open the chests, pulled out the colorfully painted saints, gold-winged angels and intricately carved wreaths, and brandished them triumphantly in the air, sneering at the “pretty images”.

Cheered on by laughing onlookers, the youths got carried away. They drove the cart to the main road, the Rennweg, and stopped in front of the Kindli Inn, where they hacked the hands, noses and ears off the statues of the saints and threw them into the fountain, whilst screaming abuse.

Carrying a St. Barbara statue to the fountain, one youth bellowed: “This false goddess helped dig up the remains of the dead, so she must take a bath in the fountain.” As soon as one statue was thrown in the water, the next was tossed in.

“This false god helped create the new calendar. In the fountain it goes,” shouted another hooligan, protesting against Pope Gregory XIII’s calendar reform. While Catholics had introduced a new calendar at the Pope’s behest, Protestant areas had refused to have their monthly chart dictated by the head of the Catholic Church. Since then, two calendars had co-existed in the Confederation, which diverged by ten days and were the source of conflict between Catholics and Protestants.

Night fell, but the youngsters continued their rampage. No one could stop them – or no one wanted to. The landlord of the Kindli sent a servant to try to stop the disturbances outside his front door. But he withdrew after the youths swore at him, calling him an “idol eater”, and threatened to throw him into the fountain.

Saviours

The night watchman, who had been alerted by a concerned citizen, could not help either. Instead of protecting other people’s property, as he was supposed to, he joined the fray and stabbed a picture of St. Anna with his halberd. The goldsmith, Stoffel von Lär, was the only one who managed to pull the articles out of the water. As an artist, he recognised their “exquisite workmanship” so hauled them to safety. His neighbour, Hyler the baker, helped salvage a statue and dragged it to the town hall for safekeeping. Other citizens were less honest. They took advantage of the chaos to steal parts of the altar with a view to selling them.

This act of vandalism triggered a serious political scandal in the Confederation. For the Catholic towns, the destruction of the altars was a direct attack on their faith. They pledged to avenge the crime by any means necessary. Meanwhile, Protestant allies in Basel and Bern were alerted. They warned the people of Zurich about the planned acts of revenge by Catholics and advised them to deploy additional guards.

In Zurich, local people were eager to pour oil on troubled waters. They listened to two dozen witnesses, made an official apology, and promised to compensate the artist and punish the guilty. Hans Feer, the cart driver, left empty-handed. Although he denied poking fun at the Zurich dead, the local council accused him of provoking the youngsters and of being partly to blame for their rampage.

Translated from German by Catherine Hickley , swissinfo.ch

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.