Researchers pinpoint genes in charge of ageing

Swiss scientists have identified a set of genes that control physical ageing in animals. Their findings could help us understand how humans can live not only longer but healthier lives.

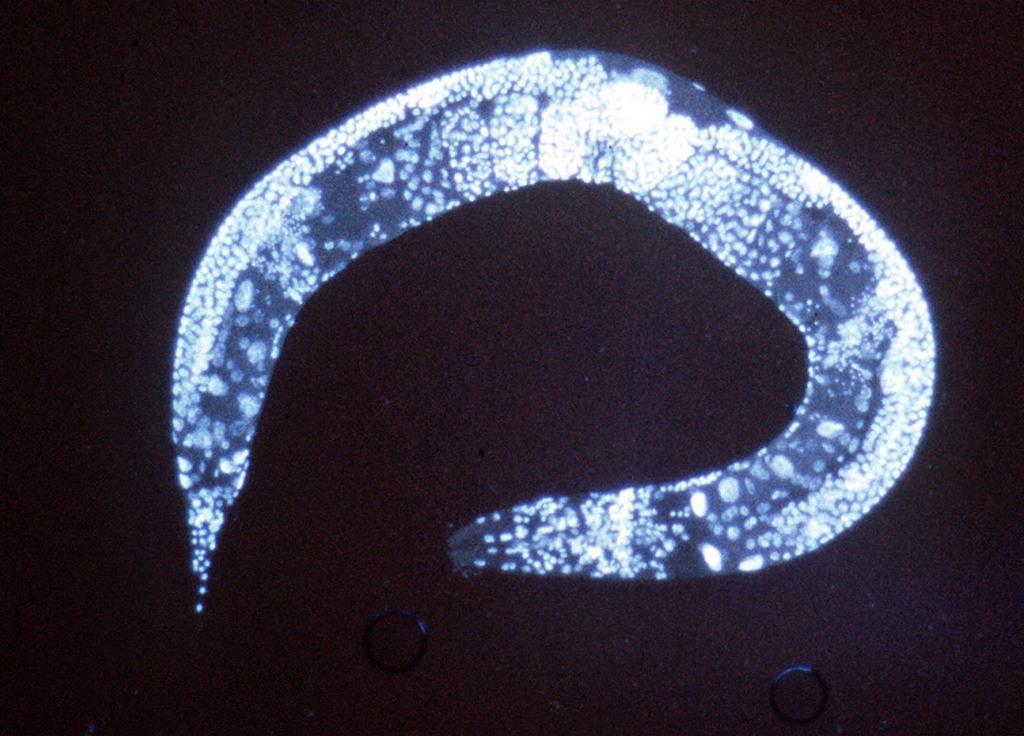

Experts from the federal technology institute ETH Zurich and the JenAge CentreExternal link for Systems Biology of Ageing in Germany screened 40,000 genes from mice, zebra fish and small worms called nematodes to find out which ones played similar roles in the ageing process.

Statistical analysis allowed the researchers to identify 30 genes that behaved the same way in each of the three organisms with respect to how active they were in different stages of life. Genetic activity was measured based on the output of messenger RNA, or mRNA – a molecule that acts as a transcript of DNA and a blueprint for protein formation.

Crucially, the genes the researchers identified were shared among the three organisms, meaning that they were derived from a common evolutionary ancestor – of which humans are also descendants.

“We looked only for the genes that are conserved in evolution and therefore exist in all organisms, including humans,” explained Michael Ristow, the coordinating author of the study and a professor of energy metabolism at the institute.

One gene in particular, referred to as bcat-1, played an especially strong role in the ageing of the nematode C. elegans: organisms in which the gene was blocked lived 25% longer than those with a normally functioning gene. The researchers think this is because the bcat-1 gene produces an enzyme that breaks down certain amino acids, which are essential components of proteins. Without the destructive enzyme around, more amino acids accumulated, causing a molecular signalling cascade that ultimately increased the nematodes’ longevity.

Staying healthy

In addition to lifespan, the researchers found that C. elegans’ health – measured in terms of indicators like speed of movement and frequency of reproduction – also improved when the bcat-1 gene was prevented from functioning. This could be particularly important for understanding our own health and longevity.

“The point is not for people to grow even older, but rather to stay healthy for longer,” Ristow said.

The researchers are already planning further studies in which they will add human health parameters like cholesterol or blood sugar levels.

The results have been publishedExternal link in the scientific journal Nature Communications.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.