Swiss vote again on genetic screening

One year after the Swiss electorate accepted a constitutional amendment allowing preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD), the question is again being put to the vote.

Pro-life groups are attacking the law implementing the amendment via a referendum, but they are not the only ones going into battle – parliamentarians across the political spectrum also believe the new text goes too far.

As soon as the constitutional article was accepted (by 61.9% of voters), conservative Christian circles called for a referendumExternal link against changing the lawExternal link on medically assisted reproduction. In December 2015, over 58,000 valid signatures were handed to the Federal Chancellery – some 8,000 more than the required minimum.

But why vote again one year later on a matter that seemed decided? Before the verdict of June 2015, Switzerland was the last country in Europe to still ban PGD. But while the constitutional article now opens the door to genetic screening, it gives no details on its implementation, which are laid down in the revised law.

In the first versionExternal link, the cabinet wanted to authorise PGD only for those couples at risk of transmitting to their child a serious hereditary disease that was likely to develop before the age of 50, and for which there was no cure. But parliament has now gone further than that.

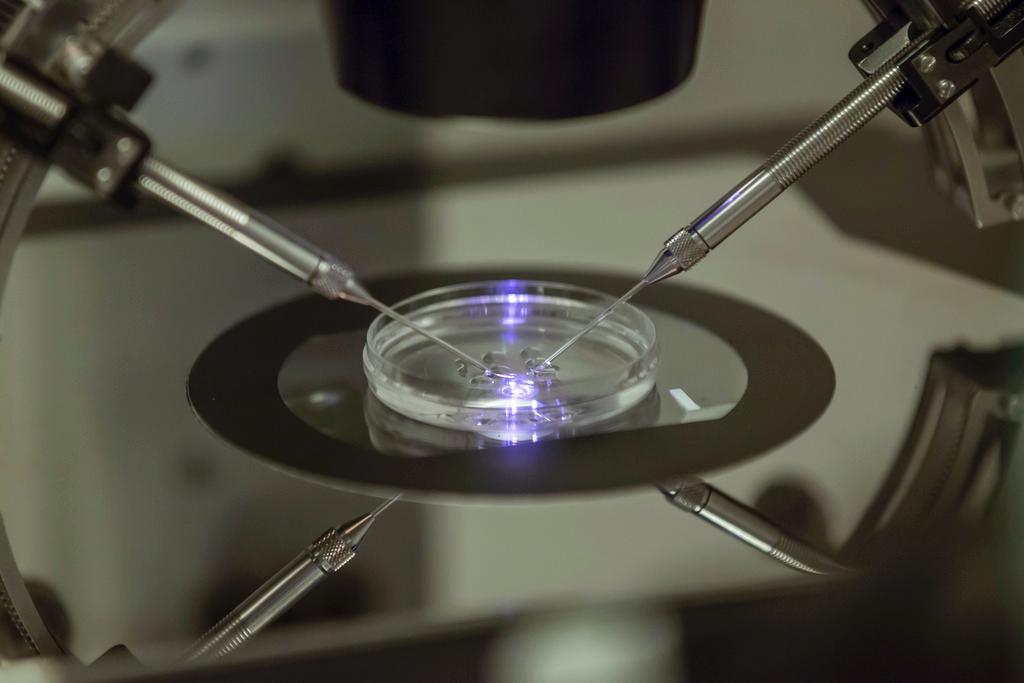

The final version of the law establishes that all embryos conceived in a test tube can be examined using all the genetic techniques available, and then selected. In this way, embryos with Down syndrome (trisomy 21) can be destroyed before implantation.

Diversity, equality, solidarity

Right away, the ranks of the opponents widened. There was no longer any need to invoke the Old Testament, or the eugenic fantasies of the Nazis – as the ultra conservative Federal Democratic Union, a party with close links to evangelical free churches, had done – in order to reject the revised law.

More

Bioethics: too complex for direct democracy?

The attitude of various associations of the disabled is a clear case-in-point.

Whereas they were divided during the 2015 campaign on the constitutional article, now almost all of them are in the “no” camp, united in their call for “an inclusive and supportive society” in which “people with and without disabilities live together in equality”.

Some politicians, too, are crusading against the law, even though they supported the constitutional article. This is the case for Social Democratic Party parliamentarian Mathias Reynard, who sees no contradiction.

“I’m not defending fundamentalist positions. We cannot turn our backs on progress. I supported the constitutional article because I am in favour of PGD for couples for whom there is a known risk of transmitting a serious hereditary disease. In these specific cases, it is fully justified to my mind. But parliament has gone too far,” says Reynard, who co-chairs the cross-party committee campaigning for “no”.

The committee certainly lives up to its name. As is so often the case when ethical questions are at stake, PGD is not a left-right issue.

Personal values clearly prevail over party lines. Thus, the committee includes representatives from across the political spectrum, with no particular group dominating. And the title of their campaign makes clear what they want: “No to this law on medically assisted procreation”.

“I was 100% in favour of the cabinet bill. And if the ‘no’ vote wins on June 5, I am ready to work on a new version,” says Reynard.

῾A setback for women’s rights᾿

“We’re back at the drawing board. Why have they launched this referendum, seeing that over 60% of people voted for the constitutional article?” wonders Liberal Green Party parliamentarian Isabelle Chevalley, who has joined a cross-party committee supporting the new law.

While she is ready to “launch a campaign to explain”, she cannot hide her irritation at “all those men who defend ethical principles, but pay no heed to the physical and moral suffering of women”.

In her view, rejecting this law would constitute “a clear setback for women’s rights”.

“Today we have prenatal diagnosis and the right to abort in the first 12 weeks of pregnancy. These were obtained, I would remind you, after a long struggle. I don’t see why we should force a couple to have, for example, a child with Down syndrome, on the pretext that a one-day old embryo is entitled to greater protection than a three-month old foetus. It just doesn’t make sense,” Chevalley argues.

Slippery slope

“The law that we are voting on profoundly modifies the original intention of the cabinet,” counters Reynard.

“Above all, we are moving from a principle of limited access based on very strict criteria to one of opportunity, by extending the screening [which reveals almost everything about the embryo] to all couples using in vitro fertilisation. I fear we are getting into very deep water.”

Reynard adds that he is “very aware” of the arguments of the associations of disabled. “If we authorise PGD broadly, the parents of a disabled child may be told ‘well, you had a choice.’”

Chevalley dismisses these fears outright. “The law’s opponents claim that preventing the birth of a child with Down syndrome is eugenics. But there are enough safeguards in the text to prevent abuses.”

As for the argument that disabled people would risk being stigmatised if they were fewer in number, she cannot believe her ears.

In her view, any association of disabled should be absolutely delighted to see technological progress that helps drive back disability.

“When I heard that argument for the first time at a meeting, I thought they would never dare bring it into the public debate. And yet they have! Again, it makes absolutely no sense.”

Translated from French by Julia Bassam

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.