Legoland comes to Cern

The world's biggest particle physics laboratory, Cern, just outside Geneva, is in the final stages of the construction of its Large Hadron Collider (LHC).

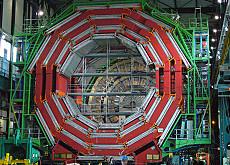

A vital element of the centre’s flagship project is the Compact Muon Solenoid, or CMS, one of six experiments being built to help probe further the origins of the universe.

Cern is a non-descript jumble of buildings just outside Geneva. Believing that billions of Swiss francs are being spent here is somewhat difficult, but that’s because most of the action is taking place well underground.

Down there, inside a giant circular tunnel that straddles the Swiss border with France, the LHC is being assembled and is now almost complete.

While most of the space is given over to tubes that are used to speed particles close to the speed of light, the six detectors used to record the collisions between protons are spread along the 27-kilometre ring.

To get to the CMS, you have to travel across the border into France to the village of Cessy. This is where, inside a huge hall standing among the cow pastures, scientists and technicians have been preparing the experiment.

Like all the detectors used for the LHC, the CMS is based on a magnet, albeit a very large one. What sets it apart is its mode of construction.

While the other experiments are being built underground, the one in Cessy was first assembled in the hall and tested before being taken apart again and lowered into its final position.

When swissinfo visited one early grey spring day, part of the detector had already been lowered 100 metres inside a vast concrete cavern. In the hall, other sections are waiting to be moved underground.

Giant Lego set

It’s not unlike a giant Lego set. The different sections of the CMS can be pulled apart and reassembled, making it easier to service.

“We wanted something that wasn’t too big and easy to handle,” said Francesca Nessi-Tedaldi, a physicist from Zurich’s Federal Institute of Technology working on the project.

“The design is very modular, with layers like a cake. Each layer can be assembled by itself.”

A short lift ride later, and the rest of the detector is revealed to the visitor. A crane capable of lifting over 2,000 tons lowered the sections of the CMS down a shaft.

When final assembly and testing are completed, the effects of proton collisions will be measured here.

What physicists at Cern hope to find is the so-called God particle, the Higgs boson. It could be last element required to complete what scientists call the Standard Model, in which 20 fundamental forces and particles are supposed to account for all forms of matter as well as light, gravity and magnetism.

The Higgs boson is theoretically one of nature’s basic building blocks, providing mass to bigger elements. The LHC was built, among other things, to prove its existence, although that will be no guarantee of success.

Surprises not excluded

“We cannot exclude what we will discover something different from the Higgs that will surprise us,” Nessi-Tedaldi told swissinfo. “Detectors like the CMS allow us to see all kinds of particles so we are confident we will find something.”

The LHC is the only project of its kind. However the CMS team faces competition from other Cern rivals in the race to find the boson.

The Atlas detector has the same goal using a different approach. Nessi-Tedaldi says though that competing teams is not a bad thing.

“It’s something we need because we need to reproduce results to validate them,” she added. “Two competing experiments are a minimum to ensure our work is correct.”

For people who might find the bill a bit too high, the Swiss physicist – who has worked on the CMS since 1989 – says that no money was wasted, even if the project relies on the generosity of its backers.

“It’s bit like working as artist in the Middle Ages, with the help of sponsors, in this case governments,” she says. “They help us because fundamental research can lead to other developments such as the World Wide Web, created at Cern.”

swissinfo, Scott Capper in Cessy

Cern was founded in 1954 by 12 states, including Switzerland, and now includes 20 member states.

Around 6,500 scientists – or around half the planet’s particle physicists – from around 500 institutes and universities have access to the laboratory.

Among the most famous developments at Cern, the World Wide Web began as a project called Enquire, initiated by British computer expert Sir Tim Berners-Lee in 1989.

CMS:

Project team: 2,300 people from 159 scientific institutes

21 metres long

16 metres in diameter

Total weight: approximately 12,500 tons

Cost of material: SFr540 million ($448 million)

Total cost of LHC (including manpower): SFr10 billion

In the LHC, high-energy protons in two counter-rotating beams will be smashed together to search for exotic particles.

The beams contain billions of protons. Travelling just under the speed of light, they are guided by thousands of superconducting magnets.

The beams usually move through two vacuum pipes, but at four points they collide in the hearts of the main experiments, known by their acronyms: ALICE, ATLAS, CMS, and LHCb.

The detectors could see up to 600 million collision events per second, with the experiments scouring the data for signs of extremely rare events such as the creation of the much sought Higgs boson.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.