Crisis response remains Nestlé’s Achilles heel

Nestlé’s slow response in tackling accusations of lead in its Maggi instant noodles in India will cost it CHF47 million, not including reputational damage. However, this is not the first time the Swiss food giant has found itself wanting in a PR crisis.

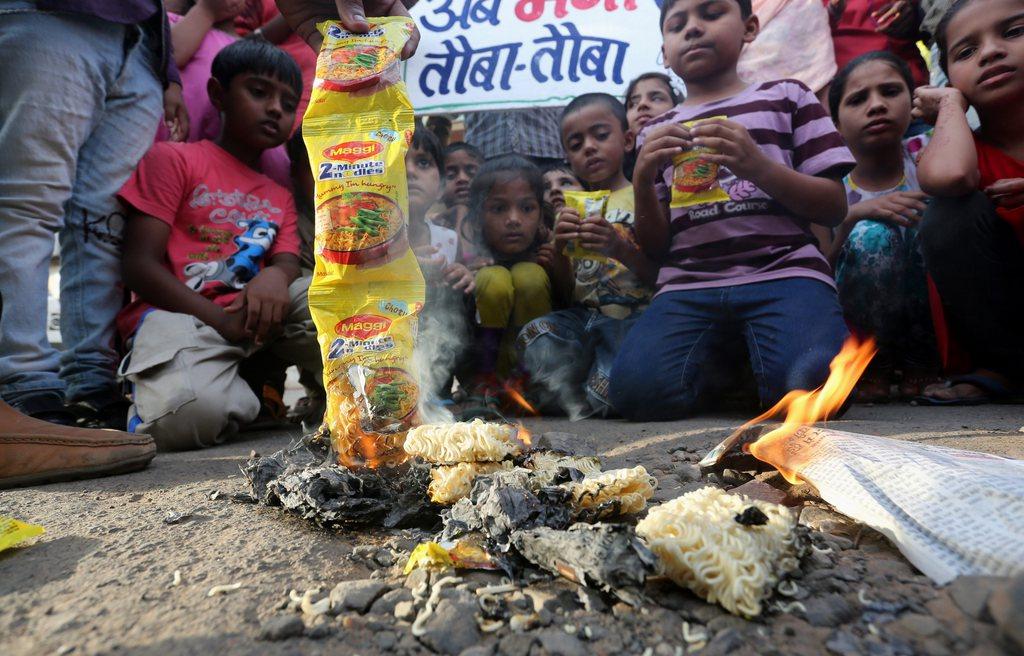

India’s food safety authority had ordered Nestlé on June 5 to recall its Maggi brand of instant noodles, after levels of lead well above allowable limits were discovered. This was followed by an indefinite ban on the products issued by the Mumbai High Court on June 12. Nestlé stands to lose over INR3.2 billion (CHF47 million), according to company estimatesExternal link released on June 15.

The first sign of trouble for the Swiss food giant came when food regulators in the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh ordered the withdrawal of a batch of noodles for labelling violations. Instead of complying, Nestlé challenged the decision which set in motion a public relations quandary for its popular Maggi brand.

On the defensive

“The first response should be honest, transparent and meaningful,” Herbert Koch, president of the Swiss-based Association of Risk and Crisis Communication told swissinfo.ch.

Nestlé’s first response was to contest the state government’s order and assure consumers that everything was alright. However, within a few days six Indian states had ordered recalls of the instant noodles. The company’s assurances that “people can be confident that Maggi noodle products are safe to eat” increasingly began to look hollow.

Nestlé was cornered into a defensive position by public outcry and was reduced to firefighting on different fronts.

“Companies should be proactive and take charge of the communications from the start,” says Koch. “If you have to respond, you’re swimming against the tide.”

“We have been, and continue to be, 100% focused on resolving this situation and getting Maggi back on the shelves, and we are doing everything possible to facilitate this, which is why this is not the time to get into discussions about our communication strategy,” a Nestlé spokesperson told swissinfo.ch.

Food policy expert Devinder Sharma states that big multinational corporations usually get away with even serious violations in India. “There is a very strong lobby comprising major industry players and advertising and public relations agencies that works on several cogs within the system to ensure not much action is taken against them.”

In the Maggi case, however, Nestlé appeared to have lost control of the narrative in the early stages. Experts agree that the media played a key role in the controversy around the presence of lead and MSG in Maggi noodles. Kavitha Kuruganti of the NGO India for Safe Food says the media has, over the last few years, been proactive with regard to food safety.

“For instance, when the Centre for Science and Environment released its findings on the presence of large amounts of pesticides in bottled waterExternal link and colaExternal link, all media outlets gave the stories top billing.”

Ghosts from the past

“Nestlé is arrogant as it is the biggest food company in the world,” Patti Rundall, policy director for the non-governmental organisation Baby Milk Action told swissinfo.ch. “They think that if they repeat something enough, everyone will believe it.”

Baby Milk Action (BMA) has been campaigning for a boycottExternal link of Nestlé for decades. According to BMA, Nestlé contributes to “unnecessary death and suffering of infants” by targeting pregnant women, new mothers and health workers to sell its products and discourages breastfeeding.

“Size was an important consideration for the Nestlé boycott,” says Rundall. “You have to go after the biggest [players] because they set market trends.”

As part of its response to that PR challenge the food giant had countered that poor water quality and malnourished mothers were to blame for infant deaths and not its own products. Various NGOs including BMA campaigned for a boycott of Nestlé and the company was labelled as a “baby killer” in a booklet published in 1974. The food giant successfully sued the publisher responsible for the German version of the “baby killer booklet External link” for libel in a Swiss court. But the judge noted that Nestlé “must modify its publicity methods fundamentally” and the case brought even more attention to the campaign.

Another PR setback for Nestlé was the Greenpeace campaign in 2010 that accused the company of abetting deforestation in tropical countries by using unsustainable palm oil in its products. To drive the message home, Greenpeace created a YouTube videoExternal link in the style of a Kit Kat advertisement that equated eating the chocolate bar with killing orangutan apes.

“Nestle is a global brand with huge public recognition,” Ian Duff, Greenpeace forest campaigner told swissinfo.ch. “With our limited time and resources we felt it was best to focus on one big company.”

Nestlé asked YouTube to remove the video citing copyright infringement. Subsequent policing of comments on Nestlé’s Facebook page only served to provoke more outrage and make the video go viral.

“When companies that always want to be in control lose control it is always going to be exciting for the public,” says Duff. “I think Nestlé should have responded to the campaign in an open and honest way and dealt with the questions being raised by the public.”

Explaining the public enthusiasm for this case, Duff shared that Kit Kat and the adverts promoting it are culturally iconic in Europe (like Maggi noodles in India). And like the lead in Maggi, Nestlé did not think palm oil in Kit Kat bars would become a major crisis for the brand.

“We had tried to engage with them before the campaign but we didn’t get anywhere,” says Duff. “They didn’t recognise the urgency of the situation.”

Damage control

While Nestlé’s crisis communications was not optimal during the Baby Milk Action and Greenpeace campaigns, it has fared much better at reputational damage repair.

“The fact is that we are today recognised industry leaders in both the area of responsible marketing of breastmilk substitutes and no-deforestation,” Nestlé’s senior corporate spokesperson Nina Kruchten, told swissinfo.ch.

She pointed out that Nestlé is the only infant formula company included in the FTSE4Good IndexExternal link, which assesses company’s breastmilk substitute marketing practices against a set of criteria, even though this is disputedExternal link by Baby Milk Action.

And despite its first response to the Greenpeace campaign, Nestlé moved into action and made big commitmentsExternal link in 2010 to halt deforestation. Kruchten noted that this commitment was the first of its kind by a food company and that a significant number of traders and manufacturers have since followed Nestlé’s lead and developed sustainable palm oil policies of their own.

“While they did handle the campaign in a very clumsy way in the beginning they did respond positively in the medium term,” acknowledges Duff.

According to crisis expert Koch, it is never too late to make amends for a poor first response.

“From a short-term business point of view, a company in such a situation could refuse to acknowledge a failure in communication and hope that people will forget and move on,” he says. “But this might not only be ethically wrong, but is also likely to damage the company in the long-term.”

Random tests carried out by the Uttar Pradesh state’s food safety authority indicated the presence of Monosodium Glutamate (MSG) in samples of Maggi instant noodles despite bearing a label stating “no added MSG”. Nestlé was asked to recall a batch of around 200,000 packs of Maggi instant noodles, which it contested. Following Nestlé’s appeal, the samples were forwarded to a laboratory where they not only tested positive for MSG but also high-levels of lead.

Within a few days six Indian states had ordered recalls of the instant noodles. Hours before being banned for sale in India by the national food safety body, Nestlé buckled under public pressure and announced the withdrawal of its products from the market on June 5.

It was at this stage that Nestlé roped in global crisis communications specialist APCO. Within a day of APCO taking charge, the Swiss multinational’s top India leadership appeared together for a joint media conference – the first since the controversy broke out. Nestlé’s CEO Paul Bulcke also flew into the country to give the efforts a boost.

The Indian media blamed the slow product withdrawal for the rapid escalation of the issue, especially on social media. Nestlé’s attempts to portray the product recall as a response to public pressure rather than to food safety concerns were also criticised. In addition, company statements referring to Indian consumers being “confused” were deemed as patronising and attempts to challenge the government’s testing protocols were seen as nitpicking.

When questioned by swissinfo.ch, Chris Hogg, deputy head of corporate media relations did not agree that the company had waited too long to recall its products or that it should have avoided references to an “environment of confusion for the consumer” or that questioning testing protocols was a wrong move.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.