Swiss direct democracy follows in Oregon’s footsteps

How do you make Switzerland even more democratic? By involving randomly chosen citizens in the deliberation process ahead of popular votes. A research project first carried out in the US state of Oregon will test that practice, in part to address populist proposals.

The project, called “A non-populist theory of direct democracy”, is financed by the Swiss National Science FoundationExternal link (SNSF) and led by political scientist Nenad StojanovicExternal link.

With his group of researchers, Stojanovic – a champion of direct democracy who says he doesn’t want to be restricted to a theoretical project – says he aims to test “an innovation connected to direct democracy which has non-populist potential”.

This text is part of #DearDemocracy, a platform on direct democracy issues, by swissinfo.ch.

It involves the so-called Oregon model, which has been applied in the northwestern US state since 2010.

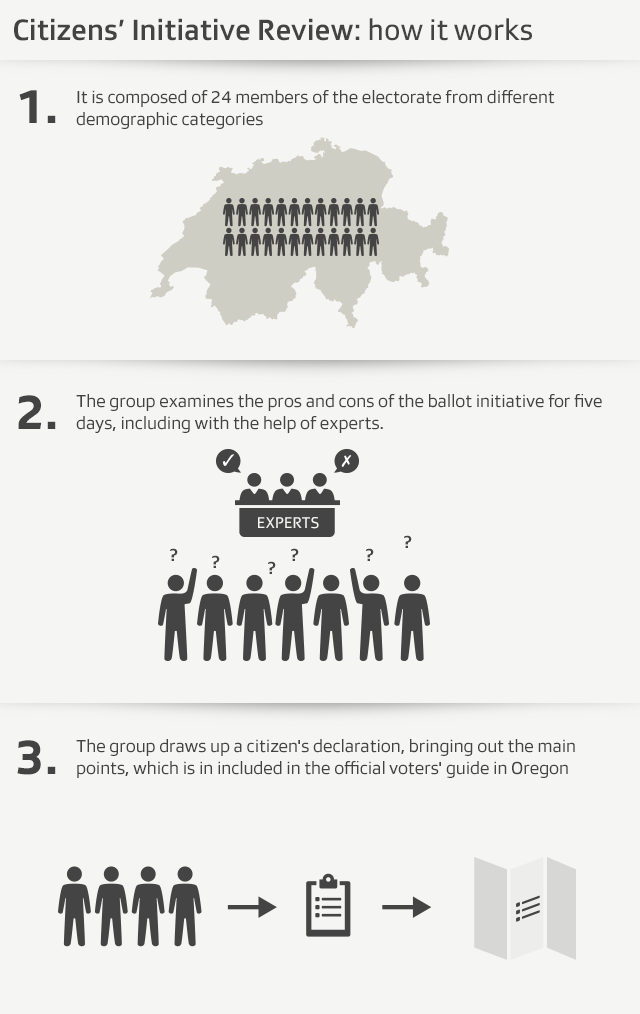

Under the model, organisers of the Citizens’ Initiative ReviewExternal link (CIR) select a panel, made up of a random sample of 18-24 citizens who are demographically representative of the population. The panellists meet for five days to learn about and discuss a ballot initiative.

This model fits particularly well to the Swiss system of direct democracy, which is similar to that in Oregon.

At the end of the CIR, the panellists write a Citizens’ Statement that sets out the facts about the initiative that they agree on, the number of panellists supporting and opposing the initiative, and the panellists’ reasons for supporting or opposing the initiative. The statement is then made available to the public and the media.

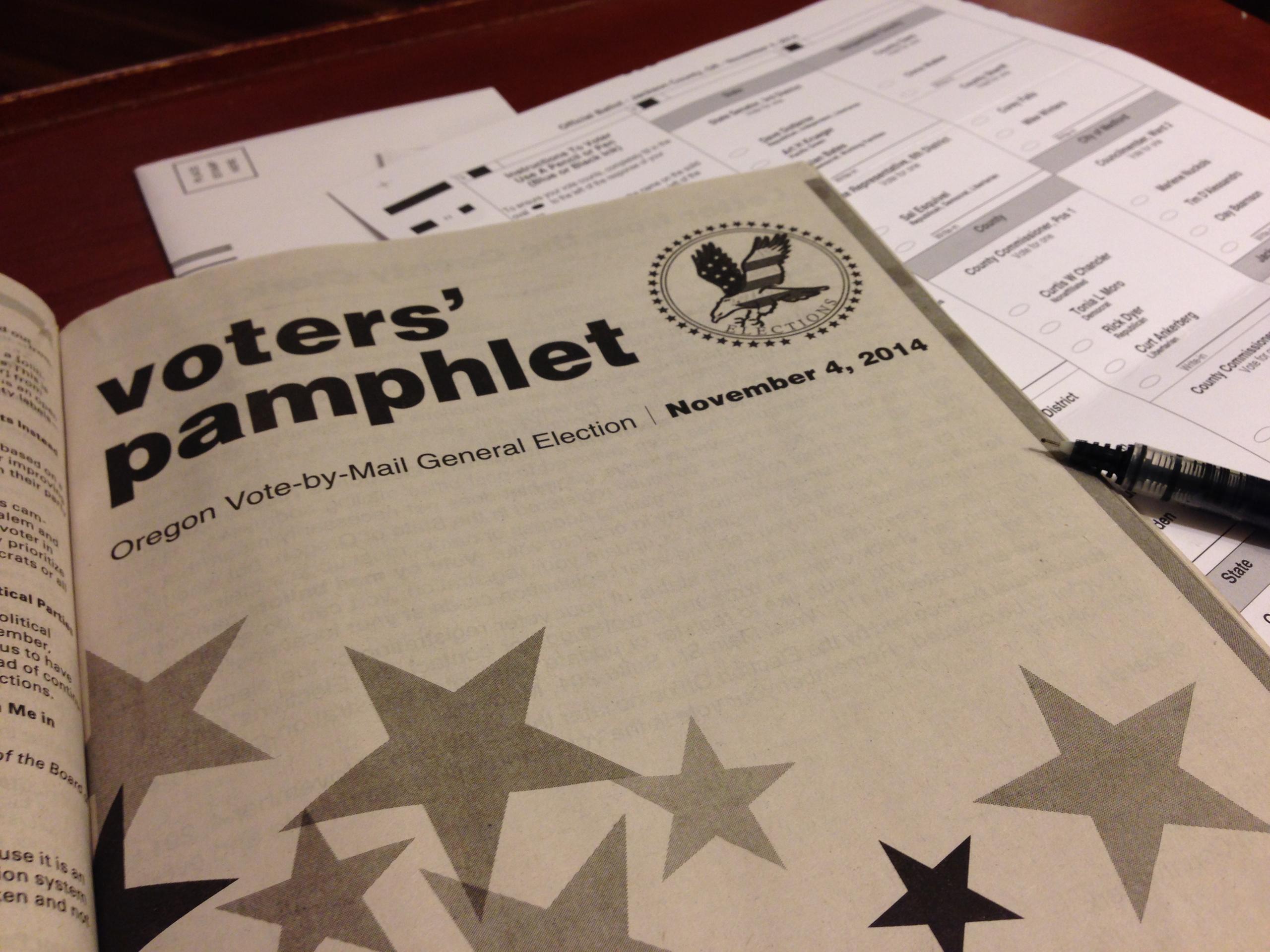

In some jurisdictions, such as Oregon, the Citizens’ Statement is included in the official voters’ guide, a booklet published by the government that gives citizens information about candidates and measures to be voted on in an election.

Studies in Oregon have revealed that more and more people “have greater confidence in the information produced by these groups of citizens than in [information] from the authorities”, says Alice el-WakilExternal link, a doctoral student of political theory at the University of Zurich and the Aarau Centre for DemocracyExternal link Studies.

El-Wakil has followed the evolution of the CIR in Oregon and urges Switzerland to draw inspiration from it to improve the quality of its own system.

Not perfect

Although she believes Swiss direct democracy offers good participatory instruments, el-Wakil sees room for improvement.

“In Switzerland, inclusion – one of the fundamental principles of democracy – is only partial. The abstention rate in votes is high,” she says.

Another sore point is information. “It’s often difficult for citizens to form an opinion on complex issues on which they have to vote,” she adds. “Then there’s the problem of disinformation, of fake news circulating – also during referendum campaigns.”

Given these points, el-Wakil thinks it would be interesting for Switzerland to explore democratic innovations like the CIR.

“Thanks to the drawing of lots, the principle of equality mostly prevails and people get involved who normally don’t,” she says.

At the same time, these spaces for discussion enable new information to reach a wider public as well as the authorities.

El-Wakil underlines that this project “has the double advantage of testing a decision-making forum and of improving the democratic procedures which already exist in Switzerland”.

Geneva pioneer

The Swiss experiment with the CIR is set to begin next year, in two municipalities for two votes.

It’s still early stages, but Stojanovic says he has seen encouraging signs from canton Geneva, where he is currently looking for the first pioneering municipality. The four-year chair of the project, funded by the SNSF, is at the University of Geneva.

As in Oregon, the 20 or so citizens who will make up the working group will be drawn by lot from the electoral list. Always following the Oregon model, the group will also include experts and a media spokesperson. The work will last five days and at the end, the group will release its own statement explaining its position.

Unlike in Oregon, the recommendation formulated by the “Geneva CIR” will not be included in the official guide sent to all voters.

“In order to be able to do that, it would be necessary to change the law on exercising political rights, which is very precise on documentation,” Stojanovic explains. The CIR booklet will therefore be distributed separately.

Populist proposals

“After the vote, we will carry out a representative survey in the municipality to measure the impact,” he says. “The interest in this process is not simply in having the discussion group drawn by lots, but also in seeing the effect. It’s important that the fruit of the debate doesn’t come to nothing.”

There’s hope for the model based on the experience in Oregon, where the CIR recommendations enjoy increasing consideration among voters. This is perhaps due not only to the fact that the position of the CIR group is the result of well-informed reflection, but also because the group of citizens selected by lot is considerably more representative than the general public when it comes to institutions, parties and organisations representing business interests.

Stojanovic hopes this model will arouse interest across his country and give a boost to Swiss direct democracy.

“If one day this model were to be introduced in Switzerland at all levels, it would enable around a thousand citizens a year to be selected, to focus on a public issue for a week, to learn how institutions work, and to understand the complexity of the material,” he says.

“What’s more, it would make the job of voting easier for all citizens and it would motivate them to do so.”

Studies conducted on this model have shown that among the groups of citizens that take part in the CIR, over the course of the information and deliberation process populist proposals lose considerable ground. At the end of the five days, they are rejected by the majority, Stojanovic says.

He wants to be able to demonstrate in Switzerland that this system reinforces popular sovereignty while at the same time closing the door to populism.

Tonight, Stojanovic and el-Wakil will start the work of convincing people of the project, when they present it at a public conference at the University of Lucerne.

Translated from Italian by Thomas Stephens

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.