Planet hunters chalk up successes

The search for extraterrestrial life has taken another step forward – even if we are unlikely to find “life as we know it” any time soon, if at all.

A team led by Swiss astronomers has recently discovered more than 50 exoplanets – planets orbiting stars outside the solar system. Their findings were presented at a conference in the United States on Monday.

Of these, 16 are “super-Earths” – planets with a mass higher than that of Earth, but considerably less than that of the gas giants of the solar system.

Only one is – just – within the “habitable” zone of its star, in other words not too close to be too hot, not too far to be too cold. This planet, HD 85512 b, is probably rocky and thus has an atmosphere and very possibly water.

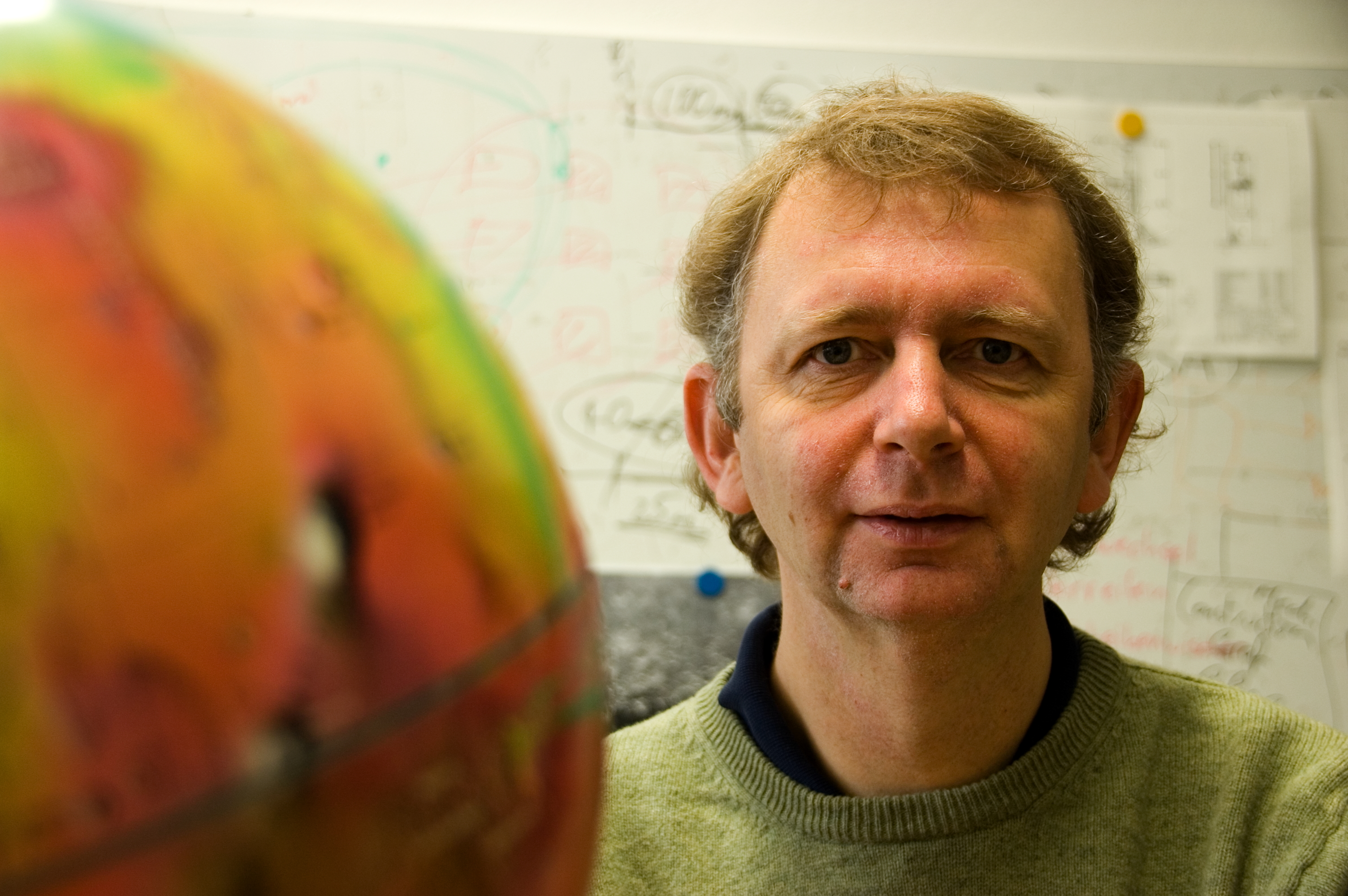

But as Francesco Pepe of Geneva University, one of the members of the team, stressed to swissinfo.ch, “habitable” doesn’t mean “inhabited”.

The most important thing to emerge from the new research is that about 40 per cent of sun-like stars have planets of a mass less than that of Saturn, he said.

Given the billions of galaxies, each with billions of stars, there must be an enormous variety of worlds. And given the huge range of life on Earth alone, it is reasonable to suspect that some of these planets also support life – though not necessarily in the form as we know it.

It is presumed that water is necessary for life, but even that may not be the case: other biochemical concepts that we know nothing of are possible.

Precision observations

The discoveries officially announced on Monday were of course not made overnight. They are the fruit of about three years of observations using the Harps planet searcher on the 3.6-metre telescope at the European Southern Observatory in the Chilean Andes.

Harps (high accuracy radial velocity planet searcher) was built with Swiss participation. It has been used to discover a total of 155 exoplanets, including two thirds of those with a mass smaller than that of Neptune.

It works by detecting the tiny wobbles of stars, caused by the gravity of planets orbiting them.

HD 85512 b is 36 light years away from our solar system; finding planets at such a huge distance requires extremely precise measurements over an extended period of time.

A lot of data have to be collected and analysed before astronomers can be reasonably certain that a planet really is there.

Competition

There is always huge public interest in extraterrestrial life, and Pepe admits that there is competition between different groups of researchers to be the first to find another “real Earth”. But he says it is important not to rush things.

“It’s only when we consider our analysis to be sufficiently advanced that we will publish it,” he said. “We could have announced our findings a year ago, and in fact it was a risk not to publish earlier, because others could have used our data.”

Astronomers make their data available to other researchers to give them the opportunity to repeat the analysis – and perhaps come up with different conclusions.

The fact is that Harps is so accurate that no other instrument can compare with it, making it hard to get independent measurements for astronomers to work on.

Even if continued financial backing for a project depends on results, Pepe says that what counts is doing a reliable job.

Meanwhile two team members are still at the observatory, continuing the programme.

Does it matter?

The idea that there may be life somewhere out there on distant planets has caught the public imagination, but astronomers see things a little differently.

“You could say finding life doesn’t matter,” Pepe admitted. “For scientists a heavy gas planet is as interesting as a rocky one, or as a planet with a very eccentric orbit, or as two planets together and the way they interact.”

He added: “I want to understand everything: how a planet was formed, how it evolved, about its star, its history, its composition, its atmosphere and so on.”

Faced with the unimaginably huge number of stars in the universe, Pepe feels humble but not daunted.

“Every new discovery pushes us to understand a bit more,” he said.

Created in 1962, ESO is an intergovernmental astronomy research organisation supported by 15 countries.

The observatory is situated in the Chilean Andes: when it was set up, all other major telescopes were in the northern hemisphere.

It offers state-of-the-art research facilities and access to the southern sky.

It has built and operated some of the most advanced telescopes in the world.

They include the New Technology Telescope (NTT), the Very Large Telescope (VLT) and the European Extremely Large Telescope (E-ELT).

Harps is attached to the ESO 3.6 m telescope at the observatory.

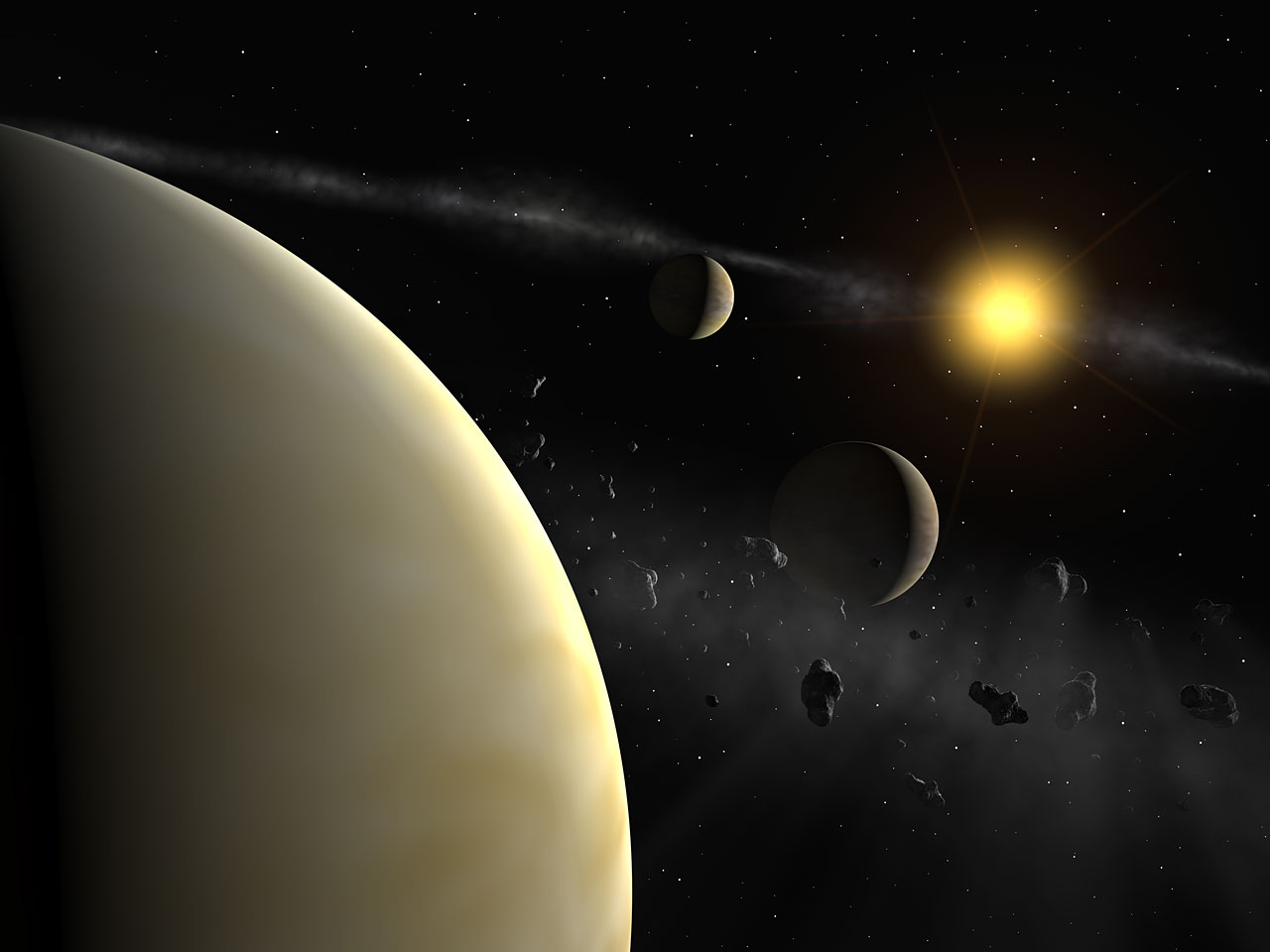

Exoplanets are planets outside our solar system.

The first exoplanet was discovered by Swiss astronomers Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz from the Geneva Observatory in 1995.

Since then some 450 exoplanets have been identified, although none can be seen by telescope. They can only be detected indirectly.

The overwhelming majority of exoplanets found so far are so-called “hot Jupiters”: large gas planets orbiting close to their star.

However, in 2007 Mayor and fellow astronomer Stéphane Udry discovered the first Earth-sized exoplanet, lying 20.5 light years or 120 trillion miles away, with a mass five times that of our planet, which is regarded as a possible candidate for sustaining life.

Udry’s team announced the discovery of another potentially life-supporting planet 36 light years away in 2011.

As of September 13, 2011, a total of 677 exoplanets had been found.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.