Defining Protestant identity

The year 2017 will mark the 500th anniversary of the publication of Martin Luther’s theses that sparked the Reformation. For Swiss Protestants, it is an occasion to reflect on their own identity. The following is an overview of the situation with Joël Burri, editor-in-chief of the Protestant press agency, protestinfo.ch.

The commemorationExternal link of the Reformation will last for the entire year. In Switzerland, the kick-off was in early November in Geneva.

“It is not a retrospective or a cult of personality. The Reformation moved hearts and minds in Switzerland, Europe and the world. This is what we are celebrating,” said Gottfried Locher, president of the Council of the Federation of Swiss Protestant ChurchesExternal link.

Even if the movement came out of Germany, neighbouring Switzerland also was very involved. “It was clearly the epicentre of the spiritual and social earthquake of the Reformation,” recalled Interior Minister Alain Berset at the event in Geneva.

But if Protestantism has a long and glorious history in Switzerland, it has now become a minority faith. We spoke with Burri to find out more about what Protestantism means today in Switzerland.

swissinfo.ch: What does it mean to be a Protestant today?

Joël Burri: The basic idea of the Reformation is that salvation is offered by God, and does not depend on the Church. One consequence of this questioning of ecclesial authority is that the relationship with God becomes more individual. From there, it goes in all directions, it is an abundance.

Those considered Protestants come from old cantonal churches but also from a charismatic and spontaneously born movement. It is a vast field that runs from creationists to the most liberal thinkers. The question of Protestant identity, therefore, is a real question.

swissinfo.ch: Aren’t the traditional reformed churches lagging behind the evangelical movements from the United States?

J.B.: There have always been movements proposing a way other than that of the traditional reformed churches. But the evangelical movement from the US does have an incredible influence on all these non-traditional churches.

That said, it is true that the evangelicals have the wind in their sails. The reformers very much envy their ecclesiastical practice, with a true group spirit and an ability to attract youth.

Be careful, however, not to overestimate the phenomenon. Evangelicals are very mobile and can find 800 people to create a church. But suffice it to say that if something goes wrong they turn to a new church. They also often end up joining the traditional reformers, for example in case of a divorce, which is viewed very poorly by the hardcore moral extremists of the evangelicals.

swissinfo.ch: What is the relationship between these two main branches of Protestantism?

J. B.: That varies a lot. It is very local. Some reformed pastors have affinities with evangelicals and others do not.

There are some very divisive themes, like homosexuality. Traditional reformers will appeal to the contextualisation of texts, while evangelicals tend to have a very literal reading of the Bible and consider it a horrible sin. Evangelicals are also much more likely to refer to Hell. On some issues, collaboration will therefore be impossible.

swissinfo.ch: Formerly the majority, protestants have become a minority in Switzerland, even in traditionally reformed areas like Vaud or Neuchâtel. Does the fact of being a minority change the situation?

J.B.: In jest, one could say this is the culmination of Protestantism. By way of saying that one is solely responsible for one’s faith and preaching individualism, this freedom is used up and one arrives at secularization.

swissinfo.ch: Doesn’t the lack of money pose a risk of finishing off the reformed churches? We have already seen temple closures or layoffs of pastors for budgetary reasons.

J.B.: A study showed that in the cantons where the churches were financed through taxes, they provided more benefits than costs to the state. Basically, it’s cheaper to have a pastor than an army of psychologists. Personally, I am not sure that this argument will hold for very long, because there is a desire to have a more secular society.

The future is thus more on the side of the situations in Geneva and Neuchâtel, where the members of the church pay their ecclesiastical taxes on a voluntary basis. But it is noteworthy that Neuchâtel has an extremely dynamic church, despite the drastic budget cuts over the past decade. The faithful who stayed are very active.

swissinfo.ch: The conflicts between Catholics and Protestants has subsided since the 1960s and the rise of ecumenism. But are there new “enemies”, for example, Islam?

J.B.: I notice it is not the people with the richest spiritual life, who put forward this logic of confronting ‘enemies’. The Swiss People’s Party, which has been staunchly defending the Christian values, is criticised hardest by the Federation of Swiss Protestant Churches and the Conference of Bishops. Indeed, the great churches are engaged in a logic of dialogue and not of confrontation.

swissinfo.ch: Churches favour dialogue because they have evolved or because they are now too weak to fight?

J.B.: Both. … The church has lost its role, which was to form society. It therefore lives among things that are more spiritual. There is a refocusing on values.

Perhaps the Catholic Church still believes itself strong enough to fight on certain issues. And an evangelical church can still afford to go to war against abortion or homosexuality. But the reformed churches are not going to do this, because they have greatly influenced society and have been strongly influenced by it. We are in a process of openness, which has been improving since the 1960s.

The ‘enemy’ is perhaps the abandonment and denial of all spiritual life, but in any case it is not the Catholics or the Muslims. But perhaps a small internal war on Protestantism cannot be ruled out, for example, when we see all the controversies about the setting up of a training for pastors in French-speaking SwitzerlandExternal link.

swissinfo.ch: What does the anniversary of the Reformation mean for Swiss Protestants? The opportunity to rejoice, to draw some new breath?

J.B.: This is clearly not a time for rejoicing, because a large part of the people regret the schism of the 16th century. Luther was a Catholic monk who just wanted to reform his church, not create a new one.

But it is an opportunity to reflect on its history and perhaps to finally discover an identity. This anniversary could therefore become a new life for the Lutheran and Reformed churches.

Protestantism in Switzerland

The origin of the Reformation is generally considered to date back to the publication in Germany of the Martin Luther’s 95 Theses on October 31, 1517. Most of these opposed the practice of selling indulgences (reducing the time spent in purgatory because of sin) to finance the construction of St Peter’s Basilica.

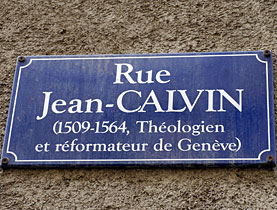

Protestantism arrived in Switzerland very early on (around 1520). The two most prominent reformers were Ulrich Zwingli (Zurich) and Jean Calvin (Geneva).

The Reformation spread mainly in urban areas (Basel, Bern, Geneva, Zurich) and was also sometimes imposed militarily, for example with the annexation by the Bernese of the Duchy of Savoy lands.

The share of Protestants, who used to be the majority in Switzerland, has fallen sharply in recent decades, notably in favour of those who declare themselves non-religious. The share of Catholics has stayed more or less stable, in particular due to the massive influx of immigrants from Italy, Spain and Portugal.

According to 2015 figures from the Federal Statistical Office, Catholics are the majority in Switzerland, with 38% of the population. The mainstream Protestant church represents 26%, Islam nearly 5%. More than 23% have no religious affiliation, compared with only 1% in 1970.

Translated from French by John Heilprin

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.