Wildhaber steps down from human rights court

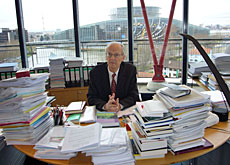

Swiss judge Luzius Wildhaber has a mountain of paperwork to do before he retires as president of the European Court of Human Rights.

Wildhaber, who is leaving after 16 years of service, tells swissinfo about his successes and challenges at the court, as well as how the organisation has changed over the years.

Based in the French city of Strasbourg, the court aims to protect the political and civil rights of Europe’s citizens. Wildhaber will leave on January 19, a day after his 70th birthday.

swissinfo: Do you consider all human rights to be of the same importance?

Luzius Wildhaber: There is a saying that human rights are indivisible. That not only sounds good, but is also basically correct. A whole set of conditions is needed for a state to be free and democratic.

We have some cases of people who have disappeared or who were tortured indiscriminately. In others we discuss whether hearing a case for five years in two courts is too long or not.

There is certainly a big difference if it’s a case of life or death, or if the case is about procedural correctness.

It would be very insensitive to understand the indivisibility of human rights as meaning all human rights have the same weight.

swissinfo: What was the most spectacular case during your 16 years in Strasbourg?

L.W.: I cannot and do not want to say. There are 46 member countries – for one country a particular issue is explosive, but for others it is something else. For Turkey it is the case concerning the Kurdistan Workers’ Party leader Öcalan or the banning of headscarves at Istanbul University’s medicine faculty.

swissinfo: What about cases from Switzerland?

L.W.: I have had hundreds, if not thousands, of cases from Switzerland. They concern procedural correctness and court independence, but often also take in freedom of speech and the press.

swissinfo: The court of human rights is completely overloaded with 90,000 cases pending. Why is the situation so bad?

L.W.: In all, 21 central and eastern European states have joined since the fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989. Some of them have large populations and some have no tradition of independent courts. As confidence in local courts is rather low, people tend to come to us.

We are a European court for a potential 800 million complainants. Two thirds of cases come from central and eastern Europe and seven to eight per cent come from Turkey. The number of cases from western Europe is under 30 per cent but it has been on the increase.

For years our budget has been much too low to deal with all these cases in an efficient way. Routine cases should be handled by the countries themselves.

swissinfo: Member states have to abide by the decisions made by the court. Is this the case?

L.W.: For the most part this works well, but there are cases which present problems. We make declaratory judgements. We say that in case XY a certain guarantee of the convention has been violated. Countries then have to report to the ministerial committee of the European Council on how they dealt with the judgement.

swissinfo: Some decisions can have political consequences. Are you a political court?

L.W.: Some of our judgements embarrass governments. No country likes to hear that it has tortured or is responsible for torture or the disappearance of a person.

We might then be told we are a political court. But I do not think we are. We certainly do not allow ourselves to be influenced by any governments.

swissinfo: Do you have influence on established constitutional states?

L.W.: Some cases have led to changes in European legislation. But in general you cannot simply achieve human rights by somewhere along the line ratifying a convention.

The concept of human rights is similar to that of democracy in that you have to work at it and continually ask questions. Now there is a lot of discussion about terrorist threats, which shows that the situation can change. Legislation on human rights has to be continually adapted.

swissinfo: Can the fight against terrorism take place in harmony with human rights?

L.W.: This issue will certainly significantly burden and influence the agenda of the human rights court for the next five or ten years. A government has to protect its citizens. People expect it as a matter of course.

But there is also the issue of how to protect the population – whether a free and open state would betray itself by doing so or whether a country that wants to be a free and open has to accept certain risks because otherwise it would have to sell its own soul.

swissinfo-interview, Gaby Ochsenbein in Strasbourg

The court, which was set up in 1959, applies the European Human Rights Convention. It has 46 member states. Every member state provides a judge.

Switzerland ratified the European Human Rights Convention in 1974.

All domestic legal means have to be exhausted before a case reaches the court. The Federal Tribunal in Lausanne is Switzerland’s highest court.

In 2005, 11,000 judgements were made at the European court. This year 50,000 new complaints were filed, two thirds from central and eastern Europe. 90,000 cases are still pending.

English and French are the court’s official languages but complaints can be filed in 41 languages.

Wildhaber was born in Basel on January 18, 1937.

He studied law in Basel, Paris, Heidelberg, London and Yale and was later dean of the law faculty and rector of Basel University.

The Swiss was instrumental in the revising the Swiss federal constitution.

He was appointed judge at the European Court of Human Rights in 1991 and became its president in 1998.

Wildhaber, who will retire on January 19, will be succeeded by Jean-Paul Costa of France.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.