75 years of human rights: what’s to celebrate?

75 years ago, the world united around a groundbreaking document. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights reflected a shared belief in “never again”, a belief that humanity needed to set rules and principles for itself, in order to ensure the horrors of the second world war were never repeated. SWI swissinfo.ch spoke with all seven living human rights chiefs to understand how relevant the text is today.

Is there anything to celebrate on this 75th anniversary? It’s worth reminding ourselves what the declarationExternal link promises: the right to free speech, to education, to not be tortured, to asylum if we are being persecuted, and much more.

According to the UN Human Rights Office, there are currently 55 conflicts raging around the world. In Ukraine, Sudan and Gaza, there is compelling evidence that war crimes are being committed.

Almost every nation in the world – 192 countries– has signed the declaration. That means our governments are supposed to guarantee us those rights and protections. But do they? Short answer: no. Long answer: not all of them, not all of the time.

Nice to have or obligatory?

The United Nations has the job of upholding the Universal Declaration. That’s tantamount to aspiring to achieve the impossible. Yet it undertakes that mission by reminding, even condemning, governments who are abusing the rights of their citizens.

The buck stops with the UN Human Rights Commissioner, a post the UN didn’t even have until the 1990s, when the cold war thawed, and there was, however briefly, a genuine optimism that multilateralism could work.

Over the course of this anniversary year, it has been my privilege to interview the men and women who have led the UN’s human rights work over the decades. You can hear all of those exclusive in-depth interviews on our Inside Geneva podcast.

Now 91, José Ayala Lasso from Ecuador was the very first UN human rights commissioner. He told me that when UN member states were negotiating the terms of the job, some governments thought the principles contained in the declaration were nice goals to have, while others thought they should be obligatory, and argued for some form of mechanism to uphold or even enforce them.

“I tried to support the second position,” he told Inside Geneva.

More

José Ayala Lasso: ‘We should not lose our faith’

Big challenges

But as we know, even with international law and conventions to support it, the UN has great difficulty enforcing anything. When Ayala Lasso took office in the spring of 1994, the war in the former Yugoslavia was raging, and the genocide in Rwanda had just begun.

Despite having a tiny office and an even tinier budget, Ayala Lasso was determined to go to Rwanda, in a bid to stop the violence. “I had to go,” he told me. But by the time he got to Rwanda it was already May, and the Tutsi leader Paul Kagame complained bitterly that the genocide inflicted on his people was “near to completion”.

The failure of the UN in Rwanda, though not the fault of the newly created human rights commissioner, impacted Ayala Lasso’s successor, Mary Robinson. As president of Ireland she had visited Rwanda several times and been warmly received. When she went representing the UN, she remembers that “when I arrived wearing my UN hat they completely disregarded, and in effect kind of humiliated me.”

Her experience demonstrates the still enormous gap between the hopes invested in the United Nations and what its officials can actually achieve. That gap was even more starkly illustrated post 9/11, when the United States, the world’s biggest superpower, began to question the most fundamental principles of human rights.

More

Mary Robinson: ‘everyone has core human rights’

Double standards

By this time, Canadian Louise Arbour was UN Human Rights Commissioner. A lawyer who served on the tribunal for former Yugoslavia, she had already made headlines by indicting Slobodan Milosevic for war crimes. That indictment was, she told me “a vindication for me of the significance of law. Of the rule of law, as an organising principle in modern society.”

But the human rights commissioner is neither judge nor prosecutor, so when the United States, in the wake of 9/11, questioned whether the law prohibiting torture should apply in the war on terror, Arbour had only the UN’s power of persuasion or condemnation.

Although today she questions how much good “screaming in the wilderness” does, she also worries that perceived double standards from western superpowers cause frustration among other countries, who feel lectured to. “As the West was promoting its so-called values” Arbour explains, “others started to notice that, happily for the West, its values always coincided with its interests.”

Any results?

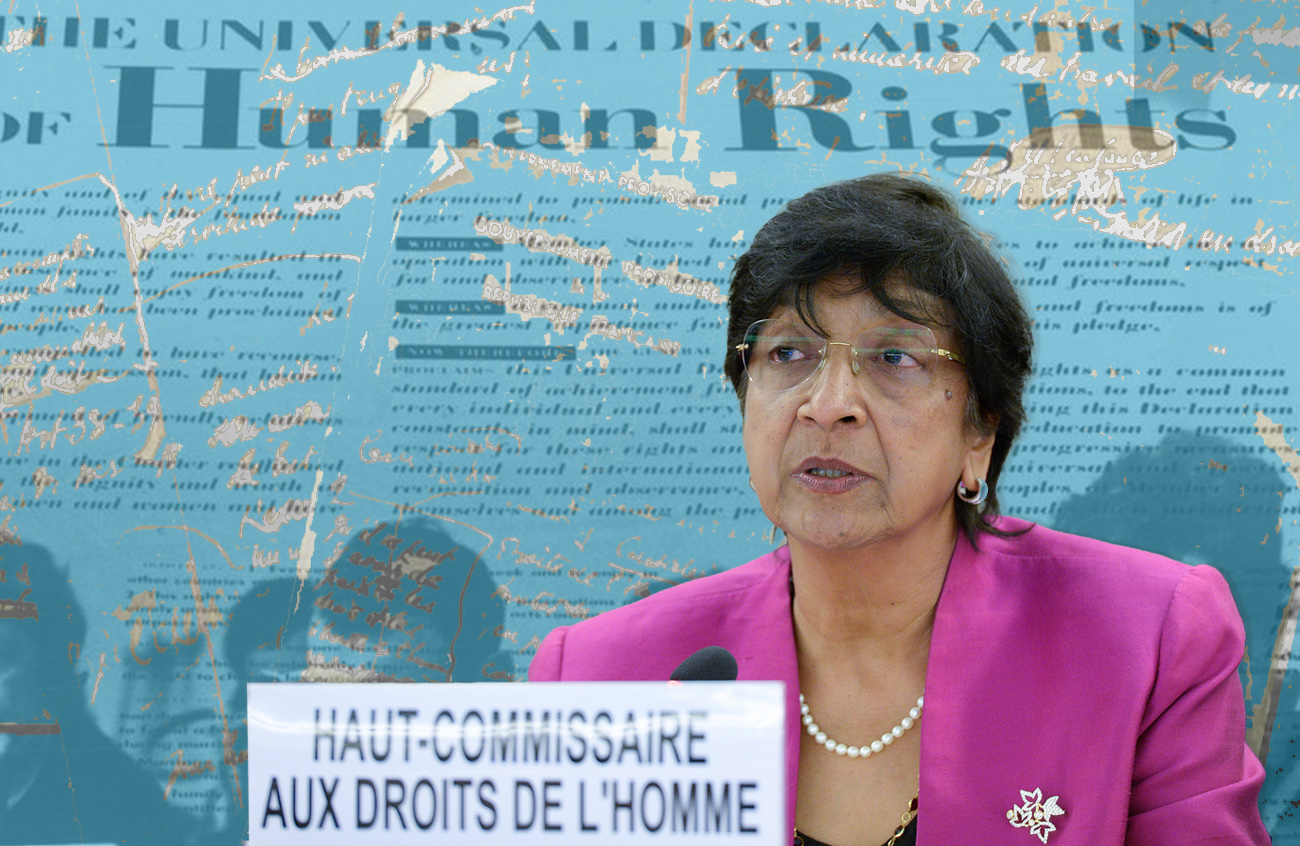

It’s fair to ask, hearing the frustration expressed by so many former commissioners, whether the UN’s human rights architecture can achieve anything at all. But that would be a pessimistic view. Look at the work of UN Human Rights Commissioner Navi Pillay, and then her successor Zeid Ra’ad al Hussein, on Syria. They produced multiple in-depth reports, examining every grim facet of the conflict, with evidence which could, at some point, be used in prosecutions for war crimes.

More

Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein: the UN ‘is not there to become friendly with member states’

More

Navi Pillay: an intrepid fighter for rights and equality

Or look at Michelle Bachelet, who left office last year. She came under huge pressure over a much-delayed report into China’s treatment of its Uyghur community. She confesses to Inside Geneva that she came under “daily pressure” from those who wanted to publish it, and from those who didn’t.

“I had to do my job,” she remembers, which meant not bowing to that pressure. When the report finally came out, it was hard-hitting, suggesting China could be committing crimes against humanity.

More

Michelle Bachelet: The Universal Declaration is ‘good enough’

Unfortunately for Bachelet, the controversy over the delay overshadowed other valuable work she did, in particular putting systemic racism, in particular from law enforcement bodies, on the human rights agenda.

To hear more about the highs and lows, the tears and the laughter of these human rights champions, you’ll have to listen to Inside Geneva. But I will leave you with a reminder that Volker Türk, the current UN Human Rights Commissioner, is determined to put the spotlight on the universal declaration, a document he calls “transformative”.

All his predecessors agree with him. “We should not lose our faith in the capacity of human beings to act correctly,” says Ayala Lasso today. “Human rights are the answer,” asserts Mary Robinson.

More

Louise Arbour: The declaration of human rights ‘is more than worth defending’

Arbour believes anyone arriving from another planet and reading the universal declaration would “think they had arrived in heaven.” Navi Pillay points out that not one of the 192 countries who have signed it have walked away from it.

Zeid Ra’ad al Hussein explains that “what we’re doing is trying to make a better human being. Who could argue with that?” Bachelet is a little more pragmatic, “the Universal Declaration is still valid. Because it gives a minimal standard, of how we can live together.”

And Türk, looking at those 55 conflicts around the world, says we must “learn from these crises” and put human rights right at the heart of everything we do. The United Nations, as ever, aspirational. Hopefully, this year, inspirational too.

More

Volker Türk: ‘If there is one single message, it’s the centrality of human rights’

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.