Ageing dams pose a growing threat for millions of people

Thousands of large dams around the world were built over half a century ago and have since exceeded their theoretical lifespan. Does this make them less safe? The renovation of the Verzasca Dam in Switzerland shows how to cope with ageing and climate change.

Civil engineer Francesco Amberg does not hide his excitement. Throughout his career, Amberg has visited dozens of reservoirs around the world, but has rarely come across such a panorama.

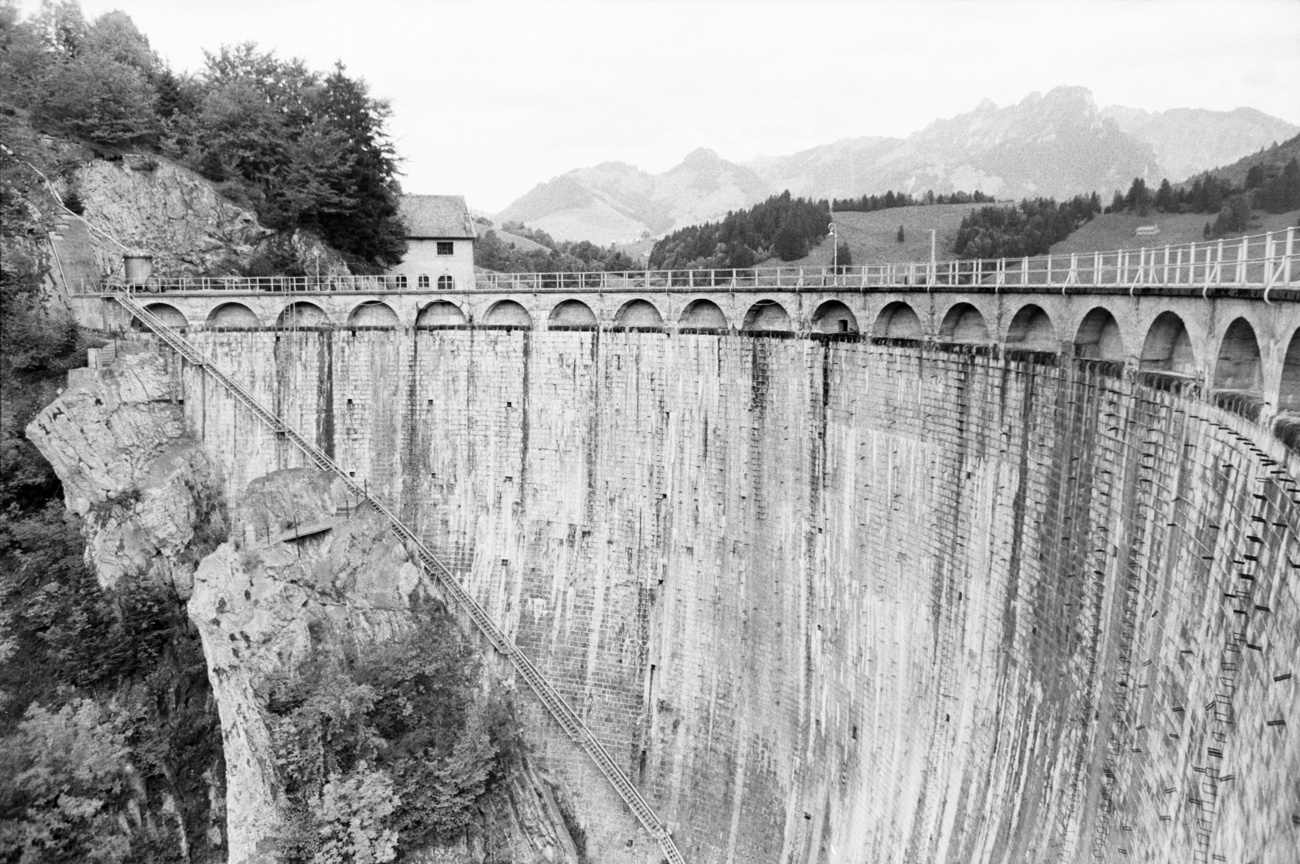

Amberg is standing on the crest of the Verzasca Dam, a few kilometres from Locarno in the canton of Ticino, admiring what remains of the reservoir below him. The reservoir has been drained and the turquoise waters have given way to a grey and barren, almost lunar landscape. “Seeing the lake almost empty has a certain effect,” says Amberg.

At 220 metres, the Verzasca dam is one of the highest in Europe. It supports a 105-megawatt hydroelectric station. James Bond made it world-famous in the 1995 film GoldenEye. It is from the top of the dam where I am standing with Amberg, on this sunny February day, that the British secret agent played by Pierce Brosnan plunged into the deep, tied to a rubber band.

After 56 years in operation, renovation work is needed.

>> Watch the spectacular images of the almost empty lake at the Verzasca dam:

The renovation of the Verzasca Dam covers all the parts that are used to channel water from the reservoir downstream, explains Amberg, one of the engineers involved. More specifically, the two butterfly valves (used to interrupt the flow of water to the turbines) are to be replaced and the corrosion protection inside the pipes is to be renewed. Work is also planned on the expansion chamber, a space carved out of the rock that serves to manage variations in the water released by the dam. Renovation will last about three months and the estimated cost is approximately CHF7 million ($7.56 million).

Expanding concrete

The arch wall, on the other hand, does not require any special work. In contrast to other dams of the same type – built in concrete – no chemical degradation has been observed. Concrete dams are at risk that water reacts with certain minerals contained in the concrete, for example silica. In time, this will make the dam swell.

This process of deterioration is known as the ‘alkali-aggregate reaction’ and also affects all major structures in concrete such as retaining walls and bridges. “I wouldn’t call it a problem a priori because the solidity of the structure is not affected. But it does need to be monitored,” says Amberg. If the concrete expands too much, engineers can make vertical cuts with a diamond wire saw to reduce internal forces in the dam.

But older does not mean more dangerous. In fact, the opposite is often true. Amberg says that he feels safer today than when the Verzasca Dam became operational in 1965. “The most critical moment is at the beginning, the first filling, the first seismic tremor.” International studiesExternal link confirm that many safety incidents occur in the first five years after a dam is commissioned.

In Switzerland, concrete dams are designed to withstand earthquakes that occur once every 10,000 years. Legislation is particularly strict when it comes to safety, says Amberg. For example, all dams must be able to discharge water quickly in order to put the system out of operation.

In addition, Swiss dams are inspected regularly and reassessed on the basis of current seismic maps. “Internationally, this is not always the case,” he says.

Dams in Switzerland are on average 69 years old

Thousands of large dams around the world show signs of wear and tear. Though ageing can compromise the functionality or safety of dams, it is often not given the attention it deserves. Regulations are often laxist and renovation is expensive. The International Commission on Large Dams (ICOLD) counts around 58,700 large dams worldwide. These are either higher than 15 metres or have a reservoir volume of more than three million cubic metres. China has the largest number of large dams, at almost 24,000.

Switzerland is among the countries with the highest density of dams: federal authorities are responsible for 188 large dams, and hydroelectricity accounts for 58% of all electricity generated in Switzerland.

Around 19,000 large dams worldwide – one in three – were built more than 50 years ago, according to ICOLD. These have therefore exceeded what is considered to be the lower limit of a dam’s lifespan and theoretically require renovation. Much of the world’s large dams were built between the 1960s and 1970s. After that, there was a steady decline in new construction, which continues to this day, primarily because of growing concerns about their environmental impact.

The lifespan depends on various factors, including the type of dam (concrete, rock or earth) and the quality of the construction materials. “Reinforced concrete dams are the ones that deteriorate the most as they are subject to a carbonation corrosion process,” Jean-Claude Kolly, civil engineer and head of communications at the Swiss Dams Committee (swissdams), tells SWI swissinfo.

Dams in Japan and the UK have the highest average age in the world, at 111 and 106 years respectively. In Switzerland, the average is 69. “That’s a relatively old age, but in the absence of alkali-aggregate reactions or carbonation it can be doubled without any problems,” says Kolly. That is, as long as the necessary renovation work is carried out.

A good example is the Maigrauge Dam in the canton of Fribourg. Opened in 1872, it is the oldest concrete dam in Europe. It was renovated in 2005 and “today it is fully functional”, says Kolly.

The risks of ageing

However, not all dams in the world are in Maigrauge’s condition. Researchers at the United Nations University (UNU) warn ageing dams are “an emerging risk” that is not yet being given sufficient attention.

A well-designed, well-built and well-maintained dam can easily remain in operation for a century. However, many dams around the world do not meet these criteria. In the past two decades, dozens of plants have suffered serious damage or collapse in the United States, India, Brazil, Afghanistan and other countries, and the number of failures could increase, according to a UNU reportExternal link published in 2021.

Ageing not only compromises the efficiency and functionality of hydropower plants. It could also threaten hundreds of millions of people. In 2050, more than half of the world’s population will live downstream from a large dam built in the 20th century, the report states.

International efforts and increased maintenance are therefore needed to address this emerging risk. Not least because the natural wear and tear on dams is compounded by the consequences of global warming. Big floods and rainfall changes may be beyond the capacity of these structures, and may cause a higher risk of collapse, says Duminda Perera, lead author of the UNU study.

Melting glaciers and thawing permafrost

In Switzerland, there is also the additional risk for the dams of increased flooding. “We are reassessing the capacity of spillways [structures used to provide controlled release of water from a dam] ,” says Amberg. What worries him most is the accumulation of timber after heavy rainfall. He says it is important to maintain the forests around the reservoirs, to prevent logs and branches from entering the lake and blocking the spillways.

As temperatures rise, permafrost thaws and mountain slopes may become more unstable. This increases the danger of a landslide in the lake and thus of a devastating tidal wave, as happened at the Vajont Dam in Italy in 1963.

Sediment brought in by glacial meltwater is another concern. Sediment has an abrasive effect on pipes and turbines and, above all, accumulates in reservoirs, reducing their volume.

At the Verzasca Dam, sediment is not a problem because the reservoir is primarily filled by rain. Later in spring, when the renovation work comes to an end, the reservoir will be gradually filled and the valley will regain its turquoise waters. From the top of the dam, Amberg takes one last look. “Who knows when I’ll ever get a view like this again.”

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.