Talks aim to secure climate finance progress

Switzerland’s top climate envoy hopes this week’s informal financing meeting in Geneva will rebuild trust to revive the stalled global climate change talks.

Ministers from 45 countries are gathering in the western Swiss city to discuss long-term financing of mitigation and adaptation measures – a crucial issue for the forthcoming global talks in Cancun, Mexico, in December.

The meeting should give important signals on how far negotiations have advanced – or not – since the United Nations climate summit in Copenhagen at the end of last year, which failed to achieve more than a limited, non-binding political accord.

Franz Perrez, the head of the Swiss delegation from the environment ministry, said the two-day informal session to “soften positions”, brainstorm ideas and create better common understanding should help get the climate negotiations back on track.

“It will help rebuild trust into the process and in each other. It will also allow us to think together outside the traditional negotiating positions,” he told swissinfo.ch during a press conference in Geneva on Wednesday.

“We need creativity to achieve a broad climate change agreement,” he added.

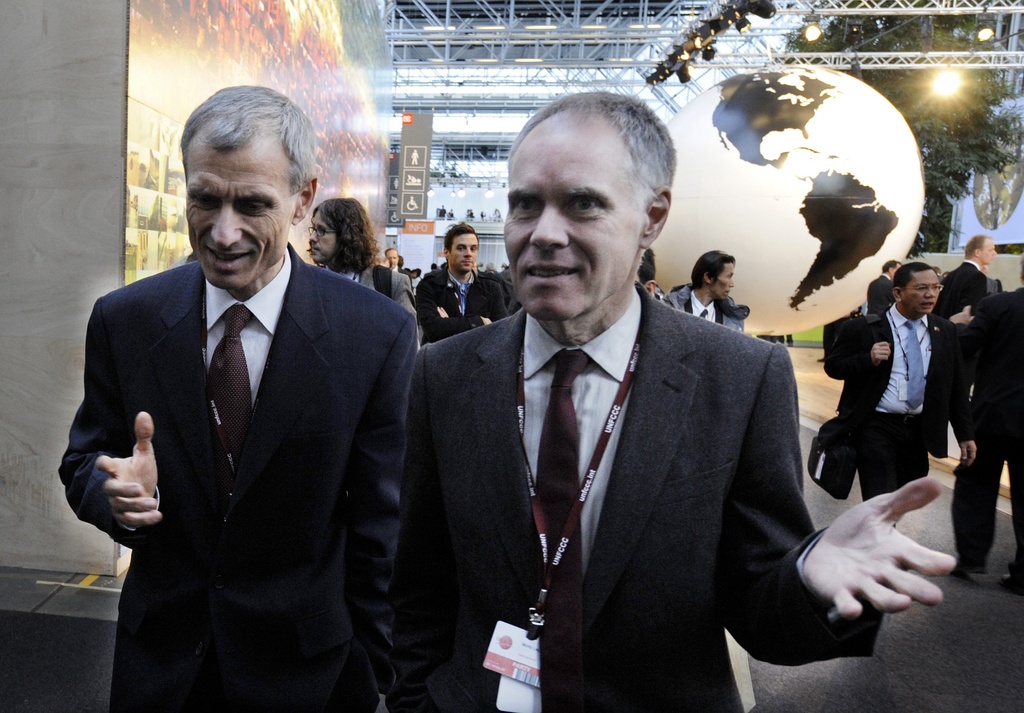

The attendance of some 20 ministers and other high-level representatives, such as US Special Envoy for Climate Change Todd Stern, was also encouraging, said Perrez.

Thorny issue

Financing climate change is a complex, thorny issue, which is seen as one of the main hurdles for any future climate change regime.

Key long-term financing questions to be discussed in Geneva include a new fund for the environment, ways to bring the private sector into financing, coordinating funding and finding new sources of finance.

“We need more reflection on a new fund’s relation to existing funds [like the Global Environment Fund], whether it is for mitigation or adaptation or both, and who should contribute and how much,” noted Perrez.

Under the Copenhagen Accord finalized last December, developed countries promised $30 billion in fast-track financing for the period 2010-2012, but the larger goal was commitment to “jointly mobilising” $100 billion in long-term aid annually by 2020.

Dressed up

Perrez said government pledges of fast-track cash for action to slow floods, droughts, heat waves and rising seas appear to have been met.

But analysts questioned whether this might be old funding dressed up as new pledges.

“It’s hard to know what’s really new and additional,” Clifford Polycarp of the Washington-based World Resources Institute, which tracks pledges by all nations, told the Reuters news agency.

Japan has promised $15 billion from its Cool Earth Partnership, the European Union plans $9.6 billion for 2010-2012 and the US is ready to set aside $3.2 billion for 2010-11.

Switzerland is asking parliament to approve fast-start funds worth $135.9 million – or 0.45 per cent of the $30 billion – based on the country’s 0.3 per cent share of developed nations’ greenhouse gas emissions, plus the fact that it is a wealthy country.

Political miracle

Hans Joachim Schellnhuber, director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, was pessimistic about governments meeting their promises, however.

“I’m afraid the promises of Copenhagen will not be realised,” he told Reuters. “It would be a little political miracle if it happened.”

Perrez agreed better coordination of funding and transparency was needed to monitor and report on promises and plans. Switzerland, Mexico and the Netherlands support the setting up of a voluntary public website to track promises.

In a statement the Swiss-based environmental organisation WWF said the private sector can and should play an important role in funding climate change, but industrialised nations should not be seen as “shirking their responsibilities”.

Perrez said he hoped the results from Geneva would feed into the Cancun talks to achieve a “balanced package of positions”, laying the groundwork for an agreement by 2012 – the end of the Kyoto Protocol – on how to create the new funding mechanism, as well as further measures to reduce greenhouse gases.

Simon Bradley, swissinfo.ch

The first UN climate conference, popularly known as the Earth Summit, was held in Rio de Janeiro in 1992. It produced an international environmental treaty, the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

A follow-up conference in Kyoto, Japan, in 1997 produced the Kyoto Protocol, with binding commitments to reduce greenhouse gases. The 178-nation accord is a 1997 annexe to the 1992 treaty that requires 37 industrial nations to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by an average of 5% below 1990 levels by 2010.

The Bali action plan adopted by UNFCCC in 2007 included five building blocks: a shared vision for a future climate regime, reductions of greenhouse gases, adaptation measures, financing and technology development. Based on this plan a negotiation process was launched.

Nearly 200 countries met in Copenhagen in December 2009 to try to reach a global agreement to follow or extend the Kyoto Protocol, which runs out at the end of 2012. The Copenhagen Accord fell short of a new treaty, setting a non-binding goal of limiting a rise in world temperatures to below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial times.

The Climate Dialogue in Geneva from September 1-2 to discuss the long-term financing of climate action will be chaired by Swiss Environment Minister Moritz Leuenberger and Mexican Foreign Secretary Patricia Espinosa.

The UNFCCC is due to hold a climate preparatory meeting in October in Tianjin, China, followed by the next major global climate talks in the Mexican city of Cancun from November 29 to December 11, 2010.

The UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) says industrialised countries need to reduce their emissions by 25% to 40% of their 1990 levels by 2020. It has called on the rich nations to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions by 80% to 95% by 2050, and developing countries by 50%.

The Swiss government proposes that Switzerland should reduce its emissions by 20% of their 1990 level by 2020.

Switzerland said it was prepared to increase its target to 30%.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.