Counting the votes, accepting the results

After weeks of tense tallying, the US Electoral College has finally confirmed the next American president. In Switzerland and elsewhere, counting takes much less time – but are the results as reliable? This and more in the latest SWI democracy briefing.

Slow and steady?

Never before did so many Americans participate in an election as in 2020 – more than 155 million cast their ballot in November to elect hundreds of new officeholders and to decide on thousands of referendums. When it came to ultimately confirming the next US president, however, it was a college of 538 electors who gathered on December 14 across the 50 states which made the decision – one that will be published officially in Congress on January 6.

The weeks since November 3 have been tense: the election’s big loser, incumbent Donald Trump, launched a comprehensive campaign to question the results. The last few weeks also offered a transparent perspective on a complex counting process which allows for many ways of questioning the outcome by legal means. But in the end, the Supreme Court clearly rejected all attempts to overturn the democratic will of voters.

What can we learn from all this? The certification and protection of proper election and referendum results is done very differently across the world, and in many jurisdictions – including Switzerland – robust results are already available a few hours after polls close.

• How election counting tames a wild democracy – and how other democracies are able to deliver results much quicker than the US, including Switzerland and Taiwan (SWI swissinfo.ch)

• Switzerland also experienced a special voting day recently, when for only the second time in history the popular vote in favour of an initiative was overturned by a majority of cantons (SWI swissinfo.ch)

• In the world’s biggest democracy there is no election “dayExternal link” – in India there are election weeks and a process that’s even more cumbersome than in America to identify a winner (Zocalo Public Square)

Democracy infected?

Meanwhile, Covid-19 is still upending not just societies worldwide, but also democracy.

The pandemic has swept through a world that was in many ways already ailing: in the past few years, more countries have experienced democratic erosion, backsliding, populist disruption and deepening autocratisation than at any time since the so-called “third wave” of democratisation in the 1970s.

But despite these challenges – or perhaps because of them – democratic aspirations have remained strong. Even in the pandemic, we have seen signs of democracy’s resilience and capacity for renewal. Innovation through accelerated digitalisation, for example, has occurred across many regions of the world – though not everywhere.

• In Switzerland, for example, digital signature gathering has not taken off in spite of Covid-19, while progress has been made in other parts of the world (SWI swissinfo.ch)

• At the same time new initiatives and referendums have been launched to deal with the legislation and challenges connected to the coronavirus (SWI swissinfo.ch)

• In a special focus on the consequences of Covid-19External link, the International IDEA group shares new data on how the pandemic has affected democracy (IDEA)

Let’s talk

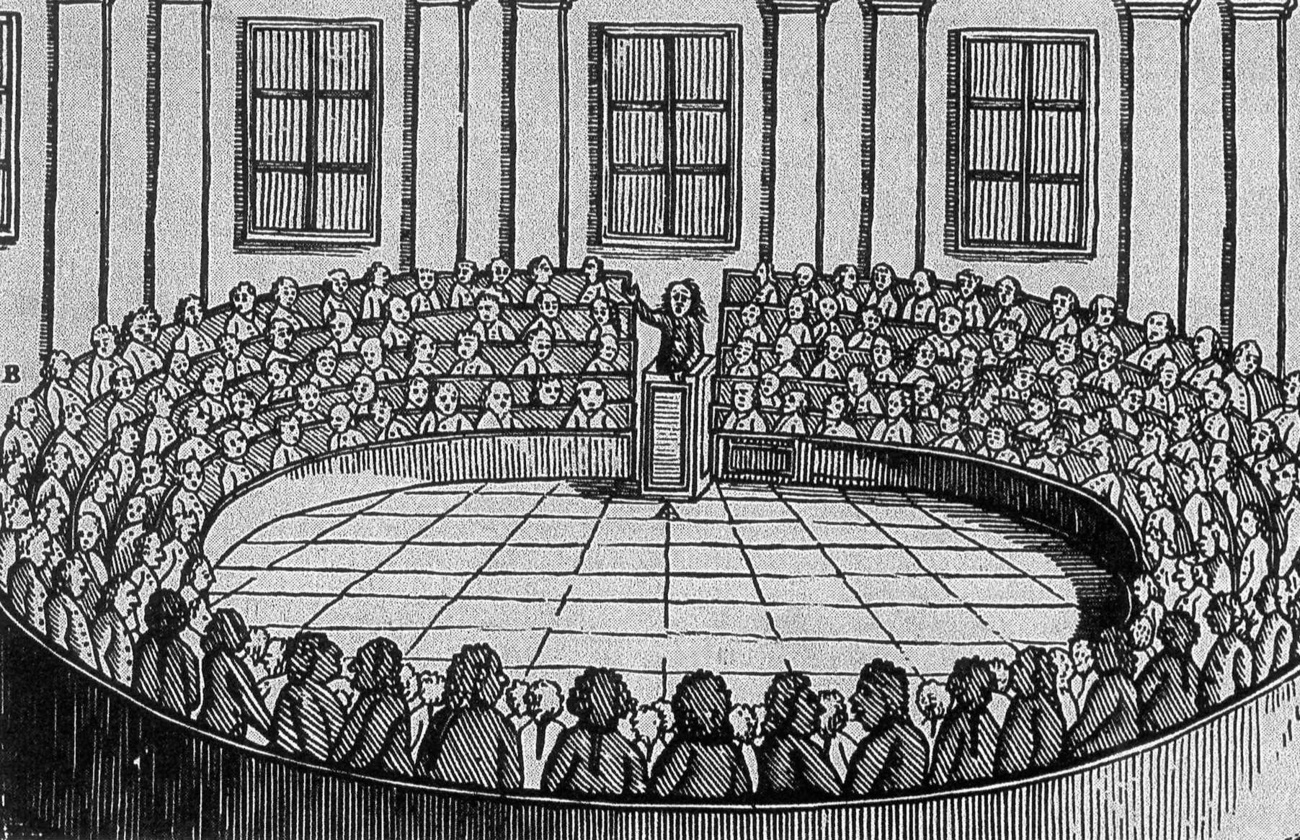

One area of democratic research – and increasingly practice – that has been booming the past few years is “deliberative democracy”: a form of decision-making based on bringing citizens together around a table to discuss a certain issue, before presenting their consensus-based ideas as possible ways to make policy.

It’s a fairly marginal form of democracy in a world still run by elected parliaments and powerful executives. But as popular protest and dissatisfaction spreads in many western democracies, deliberation is seen as a positive way of including more voices – and more representative voices – in decision-making.

Iceland set the tone a few years ago with a new constitution largely drawn up by citizen committees; Ireland has also used such constitutional assemblies to help decide on heated issues like abortion law. France has been another high-profile example of a country turning to deliberation, with its Citizens’ Convention for Climate.

• SWI swissinfo.ch recently interviewed Hélène Landemore, the Yale professor who is both a scholar and an advocate of deliberative methods; she recently released a book on the issue, Open Democracy (SWI swissinfo.ch)

• Switzerland has a long history with the ideaExternal link of open government, as researchers from Lausanne recently explore in their book “Random Selection and Politics: a Swiss History” (EPFL, in French)

• Widely hailed as a pioneer of deliberative studiesExternal link, former University of Bern professor Jürg Steiner passed away in November at the age of 86; the Neue Zürcher Zeitung writes that he “spent his life exploring the possibility of how to share power without violence (NZZ, in German)

Is there anything else you’d like to hear about from the world of direct democracy? Get in touch with our correspondents Bruno Kaufmann or Domhnall O’Sullivan

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.