Direct democracy is not just Swiss

Switzerland is not the only country to enjoy direct democracy - Slovenia, marking an important jubilee this year, is also a land of initiatives and referendums.

But, as Slovenian legal expert and politician Ciril Ribicic tells swissinfo.ch, there are important differences: the country has a constitutional court, which the court judge considers essential.

The Swiss federal court is not allowed to rule on any constitutional matters at national level. Another difference is that Slovenes also manage to marry European Union membership with popular voting rights. Many Swiss believe their sovereignty would be limited by being in the EU.

In 1990 the Slovenian population voted overwhelmingly for independence from the former Yugoslavia, with a declaration of sovereignty the following year, making this year the 20th anniversary of its formal independence.

The country is, however, currently hit by both an economic and a political crisis. The population has in particular raised questions about abuse of direct democracy for political means.

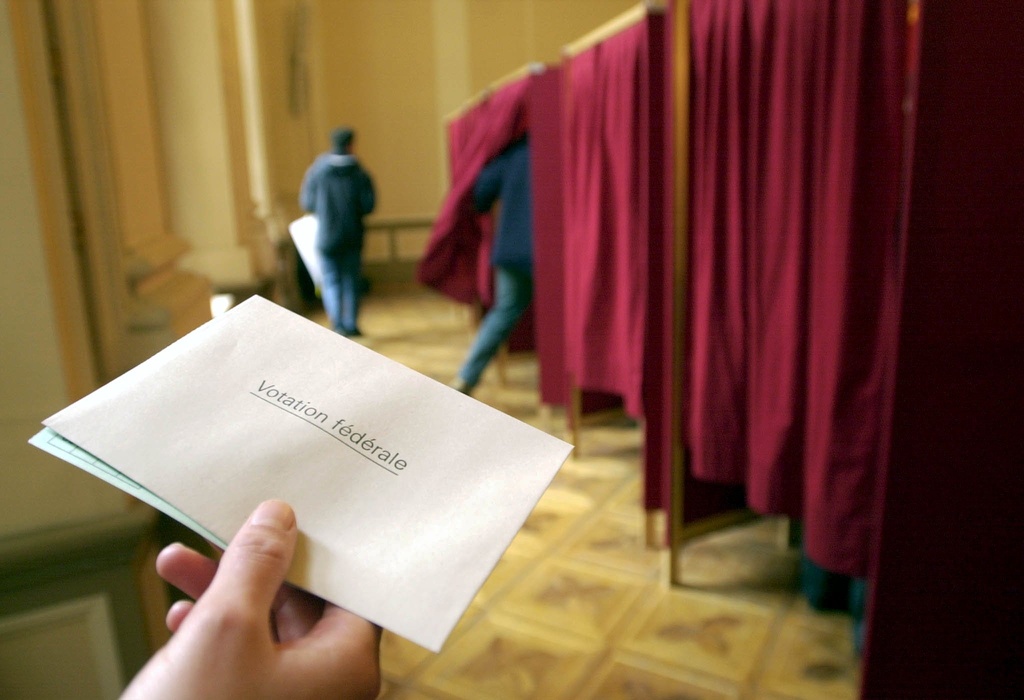

In Switzerland there has also been recent controversy about whether two people’s initiatives – on a ban on building minarets and on deporting foreign criminals – conform to international or human rights law.

swissinfo.ch: The Swiss believe that there is no need for a higher-level legal authority to check people’s initiatives and referendums for constitutional conformity. You don’t agree?

Ciril Ribicic: We considered Switzerland a model of reference 25 years ago. We already had institutional elements similar to those in Switzerland, such as the system of government in which parliament is the highest institution.

On the other hand, a constitutional court had existed in Slovenia since 1963, which we kept in 1990, when the new Slovenia began. I am still convinced that a democracy needs such a court.

swissinfo.ch: Swiss parliamentarians deal with the constitutionality of proposals. Why would we need a constitutional court as well?

C.R.: I am convinced that those who do the appraising should be outside the parliamentary process… Parliamentarians, who make laws and law proposals, should not afterwards be the ones to check them for constitutionality.

Whether this should be done by a constitutional court, as in Slovenia, or a supreme court as in Norway or the United States is another question.

swissinfo.ch: In Slovenia the compatibility of direct democracy and EU membership has never been a big issue. The Swiss feel otherwise. Why is there this difference?

C.R.: I was a constitutional court judge when Slovenia joined the EU. There were great fears that the constitutional court would be without a job, because it wasn’t allowed to intervene in European law, which superseded Slovenian law.

But our fears were baseless. Basically nothing has changed and the constitutional court has kept its role checking national laws and even those based on EU guidelines.

Nobody can dispute this role. Slovenians would never allow European law to take precedence over the national constitution. European law can supersede Slovenian law, but not the constitution.

swissinfo.ch: These are very formal and legal considerations. Pragmatically, how would you advise Switzerland to behave towards the EU?

C.R.: I think the current Swiss policy is wise and well thought out, especially at the moment when there are such huge problems within the EU. Switzerland takes what she needs from the EU without binding herself too closely.

On the other hand, I think it wouldn’t be very useful for Switzerland to leave the Schengen agreement [on border controls]. Of course a common market brings problems such as migration, but it has big advantages for the economy.

Switzerland can also, politically, keep out of Greece and Portugal’s budget problems.

I would, from a Slovenian perspective, welcome Switzerland joining the EU. But if I’m honest, if Slovenia was in Switzerland’s shoes, I also wouldn’t be rushing towards membership.

Slovenia: population around 2 million – 40,000 voters or the majority in the smaller parliamentary chamber can demand a referendum. Critics point to the fact that in the larger chamber only 30 out of 90 parliamentarians can demand a referendum. This was instituted to protect minorities, but many Slovenians believe that politicians use it for their own means, slowing down government work. For a bid to change the constitution at least 30,000 signatures are needed and at least 5,000 signatures are needed to propose a new law.

Switzerland: population almost 7.9 million – 50,000 signatures needed in 100 days for a referendum (to change laws); 100,000 signatures over 18 months for a people’s initiative to change the constitution. It is considered relatively easy in Switzerland to gather signatures.

There has been controversy over two recent initiatives: to ban minarets in 2009 and to deport criminal foreigners in 2010 – widely seen as a violation of both the Swiss constitution and international human rights law. The government has drawn up proposals to give parliament greater powers to reject initiatives that are against constitutional and international law, which are under discussion.

In the 1980s both Ribicic and Milan Kucan, the later Slovenian president, were active members of the reformist League of Communists of Slovenia.

In 1990 he was chairman of the Slovenian delegation which withdrew from the congress of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia. This step started the process of the dissolution of the former Yugoslavia.

In the same year he was elected the first president of the Party of Democratic Renewal (the former league of communists).

As one of the two main leaders of the Slovenian Left, he led the opposition until 1992 and then became one of the architects of the grand coalition of four main political parties, including his own.

In 1993 he started to withdraw from politics, devoting himself to his academic career instead.

In 2000 he was nominated to the constitutional court.

(Adapted from German by Isobel Leybold-Johnson)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.