Ethics committees fill moral vacuum

Switzerland has seen a huge growth in ethics committees over the past decade, set up to offer guidance to both the government and the private sector.

Rapid advances in science, particularly in the field of medicine, mean politicians and business leaders find it increasingly difficult to assess future risks and benefits.

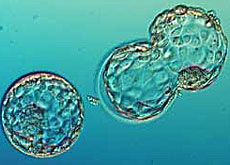

Genetically modified organisms, human cloning, stem-cell research and the production and storage of embryos for therapeutic purposes are just some of the issues that have raised perplexing moral issues.

Though accustomed to debating a wide range of topics, Swiss parliamentarians and members of the government are increasingly out of their depth when they have to face the new challenges thrown up by science.

And in many cases the full impact of the scientific or medical research project under discussion will not be felt for several years or, in some cases, decades.

Parliament also tends to be dominated by lawyers and people from the world of business. Men and women with a scientific background form only a very small minority.

Stimulating debate

To try and find a way through this minefield, the government set up two external ethics committees, bringing together scientific researchers and experts in psychology, philosophy, theology and law.

The Swiss Ethics Committee on Non-human Gene Technology was established in 1998, while the Swiss National Advisory Commission on Biomedical Ethics was set up in 2001.

“The task of the ethics committees is to evaluate the scope of scientific applications and offer a range of explanations, [potentially conflicting] opinions and recommendations,” explains Ariane Willemsen, secretary of the Ethics Committee on Non-human Gene Technology.

“But politicians cannot simply delegate their responsibilities to ethics specialists; in the end, it is their duty to take the decisions.”

For this reason, according to Willemsen, the arguments put forward by a committee are often of greater value than the recommendations it makes for or against the authorisation of a particular research project.

As part of their mandate, the two committees are also required to help inform the public and promote debate on ethical issues.

It is not only politicians who have an interest in ethical standards. For some years, there has been a growing social need for new reference points and boundaries.

As a result, more than a hundred ethics committees have been established in Switzerland in less than a decade. The cantons, too, have set up their own groups of ethics specialists, to pronounce mainly on clinical experimentation and the use of animals in scientific research.

“The need for reflection on ethical issues began to arise in the 1980s, chiefly in relation to in vitro fertilization,” explains Carlo Foppa, philosopher and ethics expert at the University Hospital in Lausanne.

“Then, over the last 20 years, with all the new challenges raised by medicine, and particularly genetic research, there has been an ever-growing need to find ethical answers to questions about the legitimacy and appropriateness of technological developments,” adds Foppa, who is one of the 21 members of the National Advisory Commission on Biomedical Ethics.

Gaps in legislation

Ethics committees have also been established by hospitals, psychiatric clinics, medical associations, and even large private companies.

Advances in science and technology are often not covered by existing legislation. Adequate laws tend not to be enacted until scientific applications have been a reality for some years.

“The question of stem cells has been considered in our laboratories, before it reached parliament,” explains Bruno Hofer, spokesman for Novartis.

“Management has sent round internal guidelines for research and has set up an ethics committee to oversee the application of these guidelines.”

Parliament has only just approved a draft law approving stem-cell research under strict conditions.

Companies, professional bodies and humanitarian organisations which cannot afford or do not need a full-scale ethics committee, have nevertheless adopted their own codes of ethical behaviour.

Sometimes, a code of this kind is also used as a way of sanitising a company’s image.

Finding a neutral forum

But the role of ethics committees is not limited to evaluating the impact of new scientific applications.

They are increasingly asked to give opinions on major issues relating to the moral values of society, for example as part of the debate on abortion or euthanasia.

Until very recently, moral authority in such matters was generally vested in the Church. Nowadays, there is an increasing tendency to turn to ethics committees, which are composed only to a small extent of representatives of organised religion.

According to Carlo Foppa, it is not the aim of ethics committees to take over the role of the Church.

“However, ethics can provide a more ‘neutral’ setting than religion for establishing norms in some sectors. This is partly because, in a secular, multicultural society such as ours, it is increasingly difficult to say which religion is qualified to lay down standards.”

swissinfo, Armando Mombelli

The Swiss Ethics Committee on Non-human Gene Technology was set up in 1998.

The Swiss National Advisory Commission on Biomedical Ethics was established in 2001.

Mote than 100 ethics committees have been established in Switzerland in less than a decade.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.