Ticino says ‘basta!’ to cross-border workers

No other canton voted as overwhelmingly as Ticino to curb the number of EU immigrants coming into Switzerland. “Stolen” jobs, lower wages and clogged roads are some of the reasons – not to mention the feeling of being ignored by Bern.

Italian-speaking Ticino, which extends into the Italian Lombardy region like a wedge, approved the rightwing Swiss People’s Party’s initiative against EU immigration on Sunday with the highest percentage of yes votes of any canton.

Precisely 68.3% of voters gave the nod to re-introducing quotas for foreign workers. “Free movement of people with the EU? Basta!” sums up the general attitude within the canton. It’s a view that has been successfully promoted by the regional protest movement Lega dei Ticinesi over the past 20 years.

Contrary to German-speaking Switzerland, where the issue of immigrant workers – for example from Germany – and problems like high rents and overcrowded trains played important roles in the outcome, the debate in Ticino focused entirely on cross-border and self-employed workers from Italy.

The text of the initiative clearly states that the flow of cross-border workers will need to be stemmed.

More

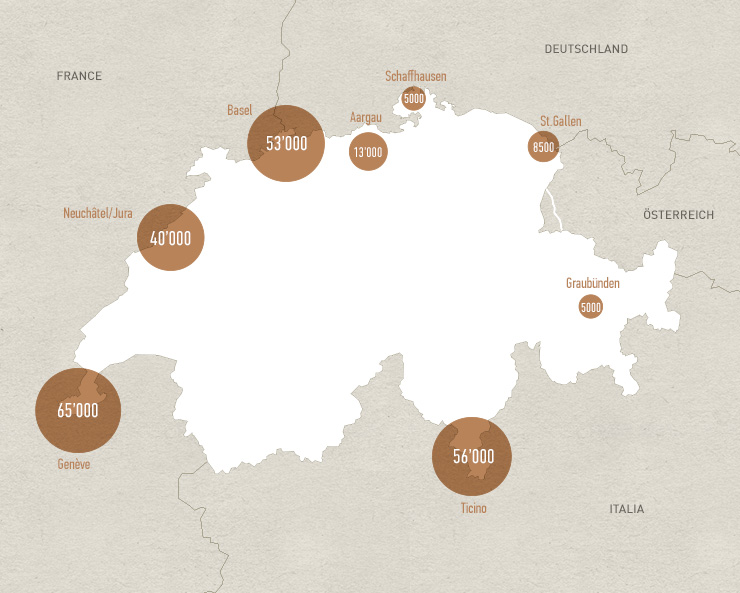

Mapping Switzerland’s cross-border commuters

Cross-border worker explosion

The number of workers who daily cross the border into Ticino has rocketed from 29,000 in 1999 to 60,000 at the end of 2013 – in a canton that’s home to just 340,000 people. More than a quarter of all jobs are held by people who live on the other side of the border with Italy.

Although cross-border commuters used to be mostly factory workers, for a long time salespeople and IT specialists have made up a significant part of the cross-border workforce. A high degree of flexibility and good qualifications, coupled with low wage expectations, make Italians attractive for employers in these sectors.

In recent years, workers sent by foreign companies have also crossed the border in greater numbers, especially craftsmen who could work in Switzerland for a maximum of 90 days a year without a permit. As plumbers or pavers, they presented the locals with price competition, which the Ticinese found hard to swallow.

Fear of job loss

For Paolo Beltraminelli, head of the Ticino cantonal government and an opponent of the initiative, the attitude in Ticino “has nothing to do with pros or cons towards foreigners”.

The member of the centre-right Christian Democratic Party points simply to social problems, saying the economic situation in Ticino is making people afraid, with many worried about their job.

There are indeed many examples of local workforces being replaced by (cheaper) cross-border workers – at least in sectors in which wages are not governed by a collective bargaining agreement.

Unlike Geneva or Basel, which as large cities attract many commuters from the surrounding countryside, Ticino is itself on the outskirts of the Milan area and Lombardy, with its six million inhabitants.

This makes Ticino a special case when it comes to cross-border workers.

Ticino, Switzerland’s only Italian-speaking canton, was always considered particularly open in foreigner surveys. In national votes, the Ticinese generally voted with the French-speaking part of the country.

For example, the 1970 vote “against swamping by foreigners”, also known as the Schwarzenbach Initiative, was rejected by 63.7% of Ticinese – more than any other canton. Nationwide, the figure was 54% against.

This tradition started to change at the beginning of the 1990s. When the Swiss voted against joining the European Economic Area in 1992, the no vote in canton Ticino was 61.5% and thus in line with German-speaking Switzerland (the French-speaking part of the country was clearly in favour of joining).

Since then, Ticino has voted no in every referendum dealing with Europe. The free movement of people and bilateral accords haven’t gone down well, with the canton practically always following the view of the regional protest movement Lega dei Ticinesi.

When in September 2005 the Swiss voted to extend the free movement of people to the ten new EU countries, 64% of voters in Ticino said no, bucking the nationwide yes of 56%.

In February 2009, when the Swiss voted on whether to extend the free movement of people to Bulgaria and Romania, 65.8% of Ticinese voters said no, the largest of the four cantonal rejections.

The vote on February 9, 2014, therefore follows the trend of the past 20 years.

Wage dumping

As a result, wage dumping and the displacement of local workforces by cross-border workers have become a long-running issue, especially as commuters jam the roads on a daily basis.

Given the economic crisis in their own country, many Italians are prepared to work for minimal salaries in Switzerland and cover considerable distances to do so.

The main thing is to get a job. The massive wage difference plays a big role here: a shop assistant can earn in Lombardy about CHF1,300 ($1,450) a month, whereas in Ticino this almost trebles to CHF3,800.

Political scientist Oscar Mazzoleni is convinced that the reflex against border workers – linked to the serious financial and economic crisis Italy has been experiencing since 2008 – is heightened in Ticino.

“People are afraid of being infected by the crisis,” he said.

Uncertainty

In addition, the Ticinese have the feeling that their problems are being ignored in Bern.

A recent refrain was that the Swiss capital wasn’t taking their concerns and fears seriously, with the result that many voters decided to send a powerful signal at the ballot box.

But the business community in Ticino is far from happy about this signal. It fears that quotas and prioritising Swiss workers when handing out jobs will mean a mountain of bureaucracy for companies – ultimately to Ticino’s detriment.

Skilled workers are hard to find in Ticino. Hotels and restaurants depend wholly on foreign staff. For Luca Albertoni, head of the cantonal chamber of commerce, “uncertainty is the only certainty”.

He simply hopes that when it comes to working out the quotas, not all groups of foreigners – resident foreigners, cross-border workers and asylum seekers – will be lumped together.

‘Alarming’

The Ticinese aren’t the only ones worried: cross-border workers from Italy aren’t happy about always being seen just as a problem. Without them, a significant part of the economy in Ticino would grind to a halt.

“It’s an alarming outcome,” admits Massimo Nobili, president of the Italian border region of Verbano-Cusio-Ossola. “The vote is a step backwards for Europe, which actually is pro-integration.”

Equally unhappy is the president of Lombardy and leader of the Lega Nord, Roberto Maroni. He says there’s a need for action to lessen the tax pressure on Italian companies and therefore prevent a relocation of companies across the border.

While Ticinese business leaders and Italian politicians moan about the vote outcome, Lorenzo Quadri of the Lega dei Ticinesi talks of a “triumph”.

He says his party expects the will of the people to be implemented promptly. “As a first step, quotas have to be introduced for cross-border and self-employed workers.”

(Translated from German by Veronica DeVore and Thomas Stephens)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.