Dictator’s son fails to show at Geneva court

A court hearing of the son of former Nigerian dictator Sani Abacha opened in Geneva on Monday - without Abba Abacha.

Abacha’s Swiss lawyer said he could not get a visa to enter Switzerland in time. He is appealing against a 2009 guilty verdict on charges of belonging to a criminal organisation and the court seizure of $350 million (SFr 385 million) linked to his father.

According to Abacha’s lawyer, Pierre de Preux, his client applied for a Swiss visa in the Nigerian capital of Abuja on Wednesday, but was told by the Swiss embassy that issuing a visa would take at least ten days.

Abacha, 41, who is accused of plundering his country’s accounts while his father was in power in the 1990s, is ready to come and explain himself, de Preux said.

“This is not a simple traffic offence case,” he told journalists, adding that he would ask the court to set a new date for the hearing.

Lawyer David Bitton, who is representing Nigeria, described the defence tactics as crass: “They are trying to buy themselves an acquittal request.”

A trial can still take place in Abacha’s absence, however.

Olivier Longchamp of the Berne Declaration, a Swiss non-governmental organisation, said he was concerned about the development.

“The trial risks being a failure because of the fact that he didn’t get a visa and that some of the 40 witnesses might not appear,” he told swissinfo.ch.

Regardless of whether Abacha arrives in Switzerland, Longchamp believes the case is still a step forward.

“There’s a real willingness to fight impunity and to punish people even if they are political personalities.”

Family business

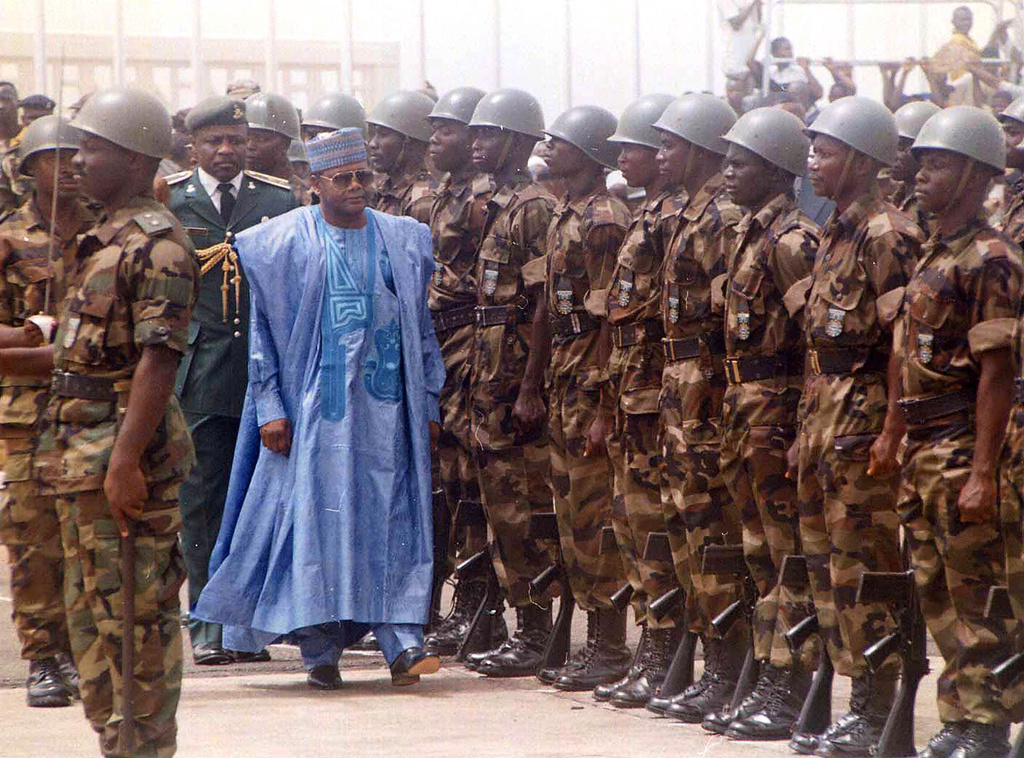

Sani Abacha rose to power in Nigeria in 1993. Between then and his death in 1998, it is believed that the Abacha clan siphoned off $3 billion from public coffers.

Methods varied from the straightforward pillaging of the Nigeria Central Bank – in some cases palettes of banknotes were delivered to the general’s home – to more sophisticated practices like embezzling public funds, fraudulent vaccination programmes or pocketing money from foreign firms working in the country.

Some $700 million of the money from these activities ended up in Swiss bank accounts or transiting via Switzerland.

According to the investigating judge, after the death of their elder brother Ibrahim in 1996, Abba Abacha and his brother Mohammed held important roles in the control of the stolen assets. Sani Abacha had ten children.

Having studied geology in Nigeria, Abba worked for the Ferrostall group in Germany from 1994-1997 before returning home.

He is accused of using false identities and passports to open over 30 bank accounts from 1996 onwards in Switzerland, Luxembourg, Liechtenstein and the Bahamas to stash his father and relatives’ money.

In the inquiry he claimed he had acted at the request of his brother, who was behind the affairs, without thinking there had been anything wrong or without knowing that it was illegal to use false names for banking transactions.

Sentenced

Mohammed was imprisoned from 1999 to 2002 in Kirikiri prison in Nigeria, charged with murder. He is now reportedly living in northern Nigeria.

Abba was arrested in December 2004 in Düsseldorf and extradited to Switzerland in April 2005. He was finally convicted in November 2009 of involvement in a criminal organisation and received a 360-day suspended sentence for the organised plundering of state coffers.

In addition, authorities confiscated $350 million from his accounts, which was collected with help from Luxembourg and the Bahamas.

He was released on bail and returned to Nigeria after serving 561 days at Champ Dollon remand prison in Geneva. Abacha has appealed the ruling and was scheduled to appear before the Geneva court on Monday, as required by Swiss law.

Successful restitution?

In 1999, Nigerian authorities asked Swiss justice officials for help in repatriating some of the funds that had ended up in Swiss accounts.

Switzerland then blocked the $700 million before giving it back to Nigeria in instalments, according to an accord both countries had signed.

The World Bank hailed the return of the funds from Swiss banks as an important precedent.

Under an agreement between the Swiss and Nigerian governments in 2005 the funds were to go to health and education projects, as well as infrastructure development.

Although Swiss officials regularly cite the restitution of Abacha money as a success story, Longchamp is not convinced.

“It’s a very complicated story,” he said. “The process was highly criticised as we don’t know what happened to a large part of the development funds – there was no monitoring.”

Simon Bradley, swissinfo.ch

Marcos, Philippines (1986 – 2003): $684 million returned to country

Abacha, Nigeria (1999-2005): $700 million returned to country

Montesinos, Peru (2002-2006): $92 million returned to country

Angolagate, Angola (2000-2005): $21 million returned to country

Kazakhstan (1999-2007): $84 million ($60 million still frozen)

Salinas, Mexico (1996-2008): $74 million returned to country

Mobutu, Congo (1997-2009): $6.7 million returned to Mobutu’s heirs.

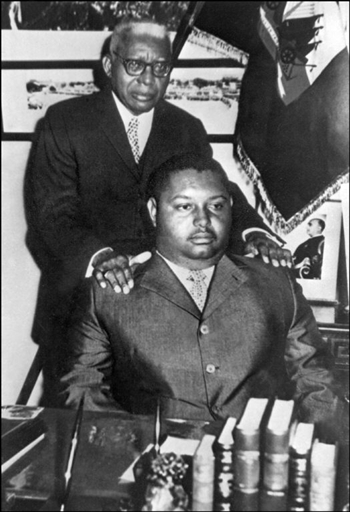

Duvalier, Haiti (1986-2010): $5.7 million still frozen

The need for a change in Swiss law became evident in connection with Swiss accounts held by the former president of Zaire, Mobutu Sese Seko, and the Duvalier family of Haiti.

The law will allow the Federal Administrative Court to confiscate frozen assets that have been illicitly acquired if the home country fails to institute proceedings. These assets would then be used to finance programmes to benefit the population there.

Under the new law the onus will lie with the depositor to prove the legal origin of the funds, rather than with the plaintiff to prove that they were stolen

If the new law is accepted by parliament and in a public referendum this year, it could enter into effect at the beginning of 2011 at the earliest.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.