Which way now for UN human rights body?

Five months after its creation, the United Nations' human rights watchdog is deadlocked by political splits that are stonewalling efforts to tackle abuses.

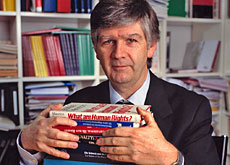

Switzerland’s Walter Kälin, who drew up the blueprint for the Human Rights Council, tells swissinfo where it is going wrong and what needs to be done.

Hailed as a new dawn for the rights of the oppressed when it started work in June this year, the successor to the widely discredited Human Rights Commission has so far failed to live up to its billing.

Divisions between developed and developing countries on the 47-strong body have been skilfully exploited by Muslim and Arab countries, leading to strong condemnation of Israel on several occasions but weak action on other pressing issues such as the crisis in Sudan’s Darfur region.

On Thursday the council finally voted to hold a special session on Darfur, a day after UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan criticised the body for failing to do so.

Kälin, a professor of constitutional and international public law at Bern University, is Annan’s representative on the human rights of internally displaced people.

swissinfo: It appears the council is no better or even worse than the old commission. Is this a fair assessment?

Walter Kälin: No. I have seen improvements in the way the council deals with reports presented by special rapporteurs. In most cases there has been serious discussion and many states took a very constructive approach – and that’s a real improvement on what I experienced in the commission.

Second, the special sessions have shown that it is possible to react quickly to situations. I wouldn’t blame Muslim states for raising issues related to Israel because human rights problems there have been real.

The problem is the council is working along the same regional lines as the commission. One of the hopes was that cross-regional coalitions of states with common interests would dominate rather than regional blocs.

swissinfo: Does the council risk becoming irrelevant as long as the US remains outside and it is dominated by Muslim countries?

W.K.: It is not dominated by Muslim countries in terms of numbers. They make up about one third. If you combine the western European group with eastern Europe and the Latin Americans with similar interests, then this group is equally strong.

It’s really down to defining positions and advancing them forcefully. If you look at some of the states from the South, they are great at doing this. They are very clever at defining positions well in advance, in creating unity among themselves and in finding allies from other regions. The western group is not doing that.

swissinfo: It has been suggested that because western diplomats tend to rotate every three years they are no match for their more experienced Arab and Muslim counterparts. Is this also a factor?

W.K.: I think this is a relevant aspect. The Human Rights Council is very demanding on diplomats. It meets almost continuously because in between sessions there are informal and formal working groups and special sessions, and this means you need to have savvy diplomats who know the system and the subject matter.

swissinfo: Right now the council is clearly not functioning properly. Do you believe it can do so in the future?

W.K.: The start has been rather bad, that’s very clear. But what we are experiencing now is a reflection of the present state of the world in general, with international relations in disarray. This is having an impact on all international bodies.

Having said that, the council will only be able to assert its authority and fulfil expectations if it manages to define its own working procedures rather quickly. I do expect that once these are in place things will, to a certain extent, calm down.

What I fear is that the present political atmosphere in the council will have a negative impact on decisions regarding the mandates of special rapporteurs and what the universal periodic review will look like. If the new framework for these important mechanisms turns out to be a weak one, then we have a very serious problem.

swissinfo-interview: Adam Beaumont

The Human Rights Council, which is based in Geneva, will eventually carry out periodic reviews of the human rights situation in member countries.

Much of its first year is expected to be spent on defining its working procedures, including mandates for UN special rapporteurs.

The council meets at least three times a year for a minimum of ten weeks and can convene emergency sessions to respond to crises. So far there have been three special sessions – all on Israel.

The council’s third session, which opened on November 29, is due to wrap up on December 8. Switzerland was elected to the council with a three-year mandate on May 9.

Africa (13 seats): Algeria, Cameroon, Djibouti, Gabon, Ghana, Mali, Mauritius, Morocco, Nigeria, Senegal, South Africa, Tunisia and Zambia.

Asia (13 seats): Bangladesh, Bahrain, China, India, Indonesia, Japan, Jordan, Malaysia, Pakistan, Philippines, South Korea, Saudi Arabia and Sri Lanka.

Eastern Europe (6 seats): Azerbaijan, Czech Republic, Poland, Romania, Russia and Ukraine.

Latin America and the Caribbean (8 seats): Argentina, Brazil, Cuba, Ecuador, Guatemala, Mexico, Peru and Uruguay.

Western Europe and other states (7 seats): Canada, Finland, France, Germany, Netherlands, Switzerland and Britain.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.