NASA prepares to launch most powerful space telescope in history

After three decades of preparations and numerous delays, NASA’s new James Webb Space Telescope looks set to soar into the heavens on Christmas Day. Swiss scientists involved in the project are watching nervously to make sure everything goes according to plan.

The lift-off of the Webb – the successor to the Hubble Space Telescope – is scheduled for December 25, according to NASA.

“The closer the launch date, the more nervous I get,” says Adrian Glauser, a scientist at the federal technology institute ETH Zurich, who has been working on the project for the past 18 years.

“It will certainly be a relief if everything happens according to plan.”

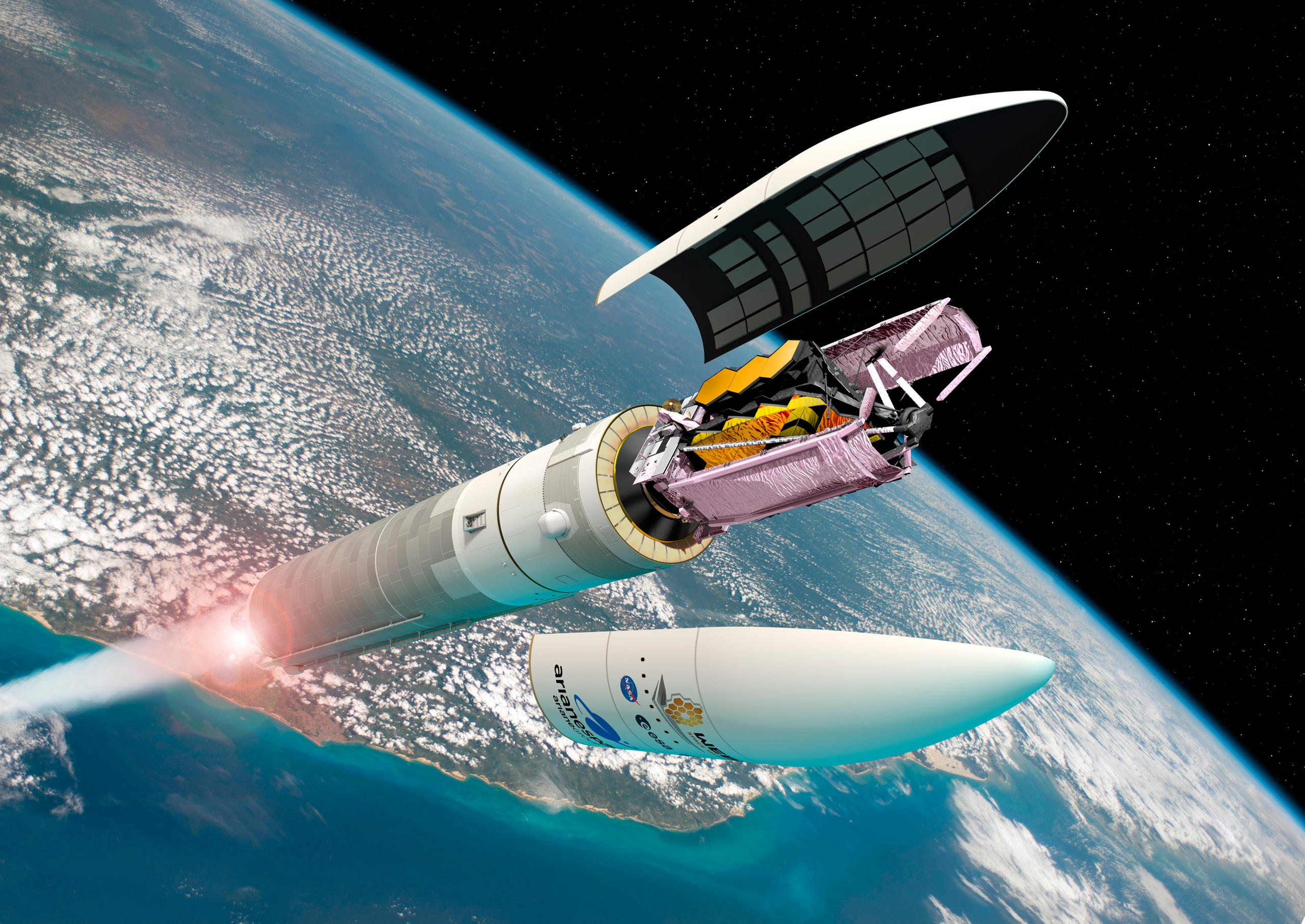

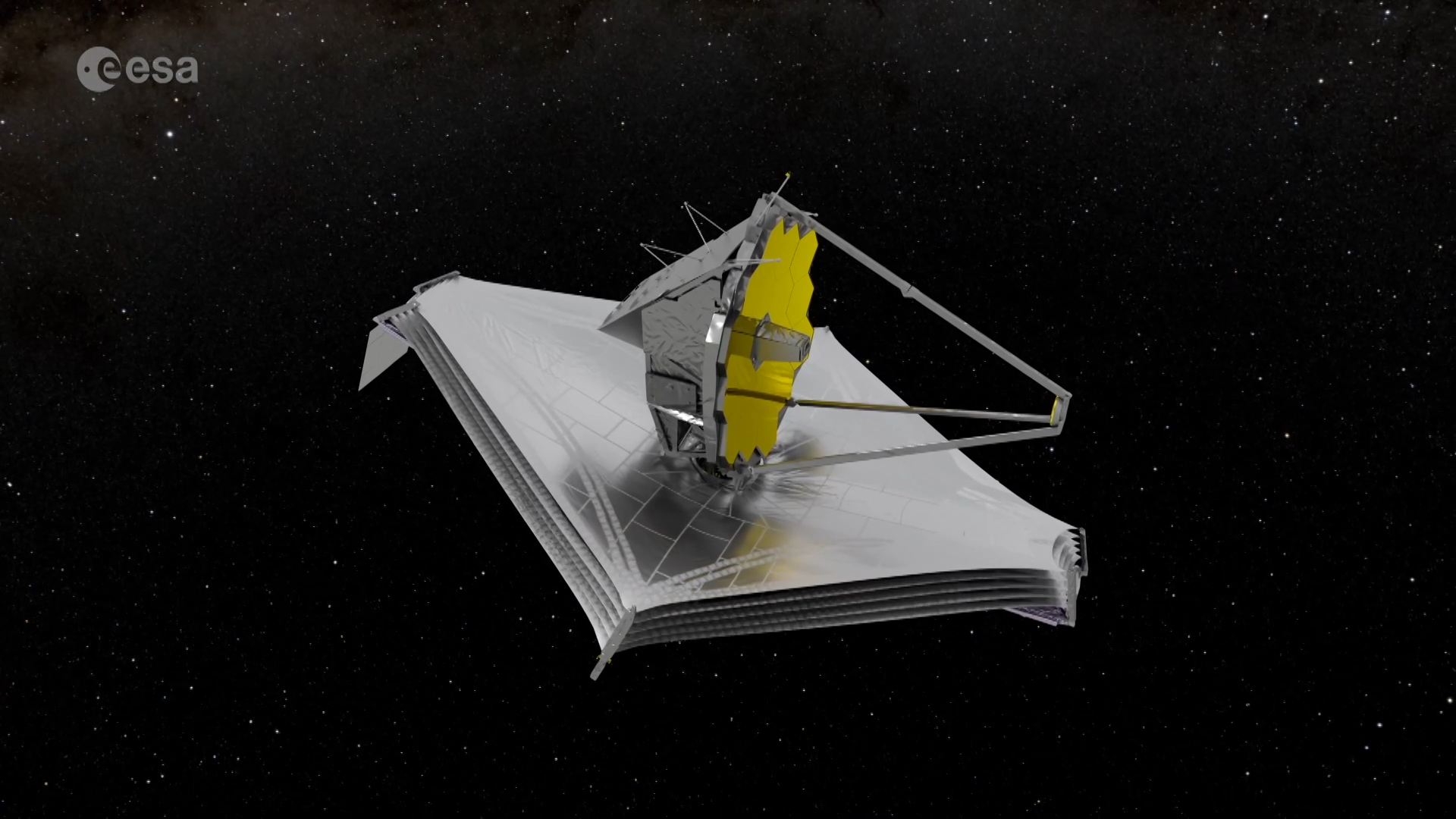

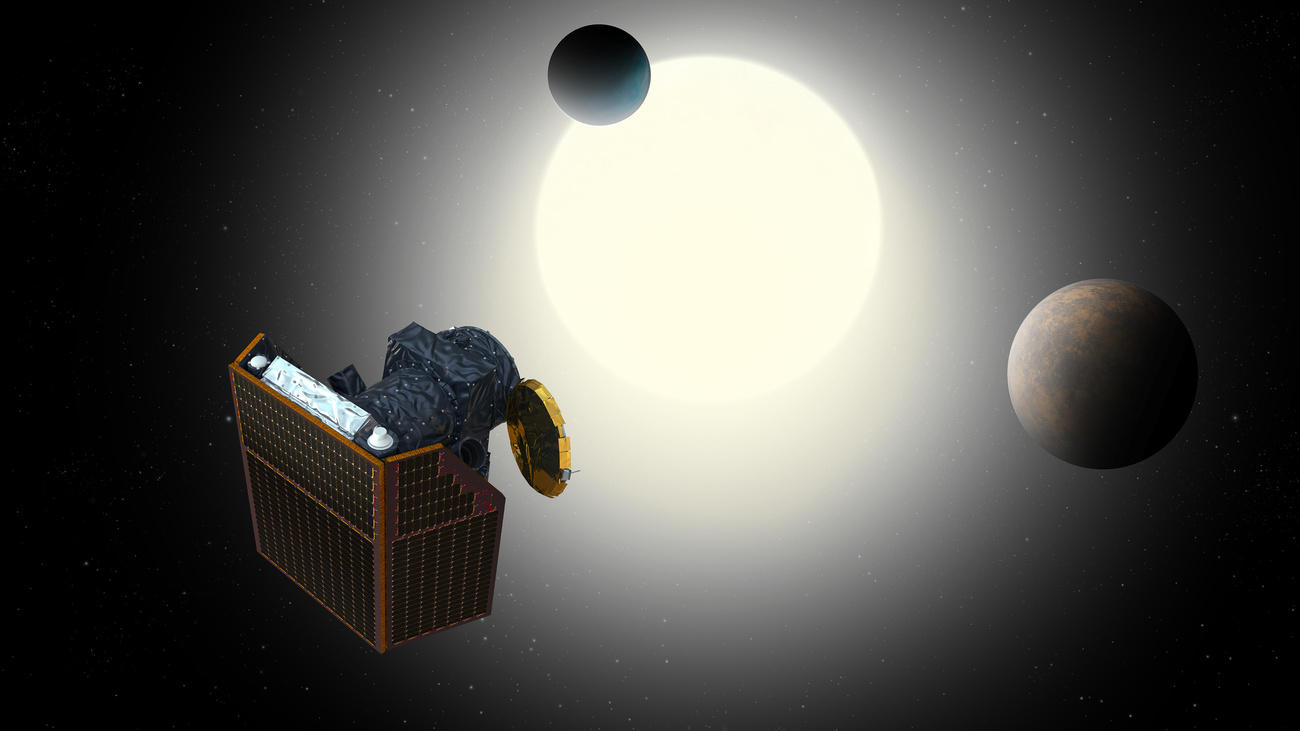

The $9-billion (CHF8.2 billion) telescope is due to blast off aboard an Ariane rocket at the European Space Agency’s spaceport in French Guiana. It will then travel on a month-long 1.6 million kilometre (million-mile) journey to its final orbit beyond the Earth’s moon. There it will begin a high-risk six-month process of unfurling its sunshield and deploying its primary mirror before it starts gazing at the heavens.

Long to-do list

The ambitious space observatory, named after NASA’s former boss, is expected to revolutionise space science as it peers into the cosmos on its mission estimated to last 5-10 years.

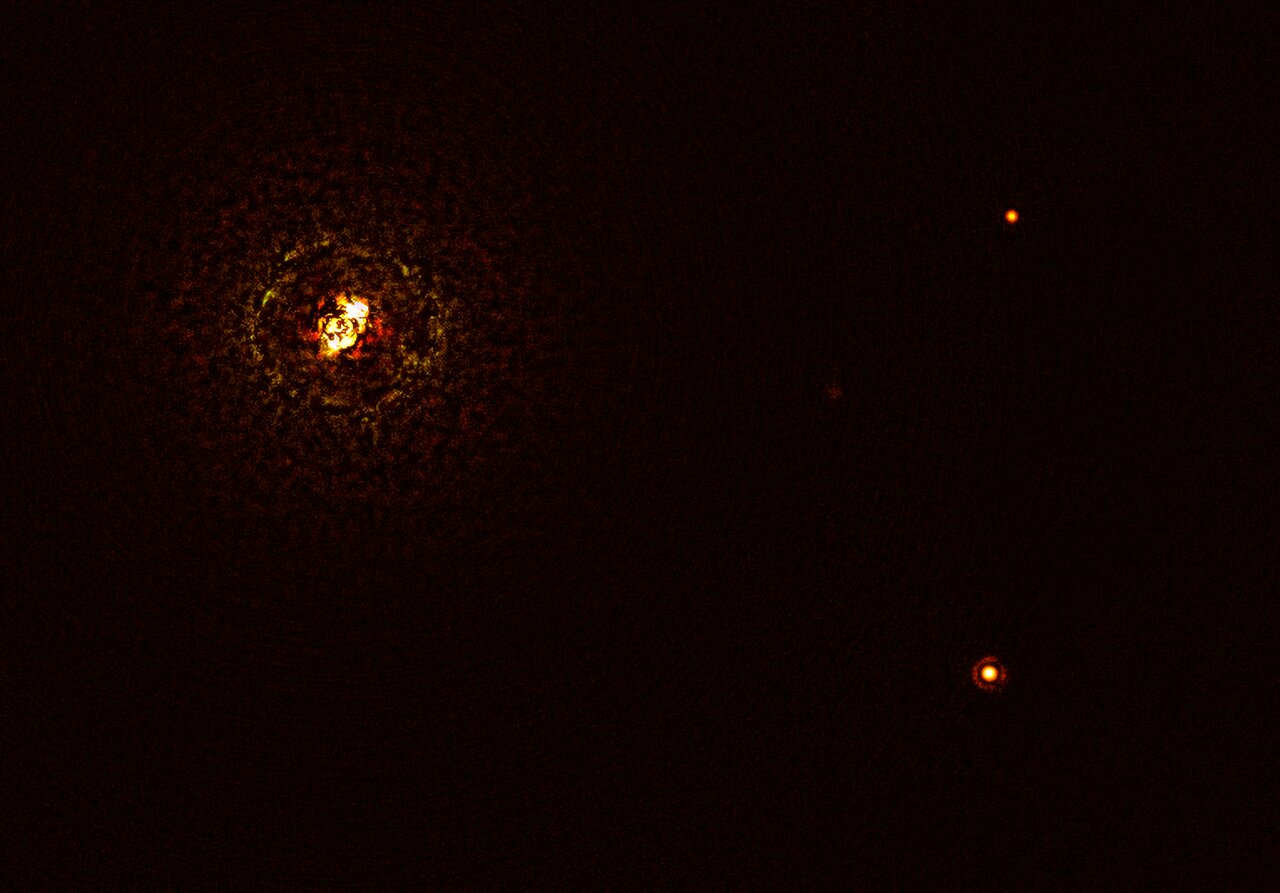

It has an impressive to-do list: collecting data on the universe’s earliest stages just after the Big Bang about 13.8 billion years ago, peering through clouds of dust to watch stars being formed and studying exoplanets – planets beyond our solar system – and objects closer to home like Mars, Pluto, asteroids and comets. Over time it will also study dark energy and dark matter.

There are several essential differences with the Hubble, launched in 1990. With a much bigger primary mirror, the Webb is 100 times more sensitive and can look greater distances and farther back into time.

The low temperature of the Webb will allow it to mainly capture faint infrared light from the first stars and galaxies, while Hubble has examined closer objects since its 1990 launch, primarily in the spectrum visible to human eyes, and in the ultraviolet.

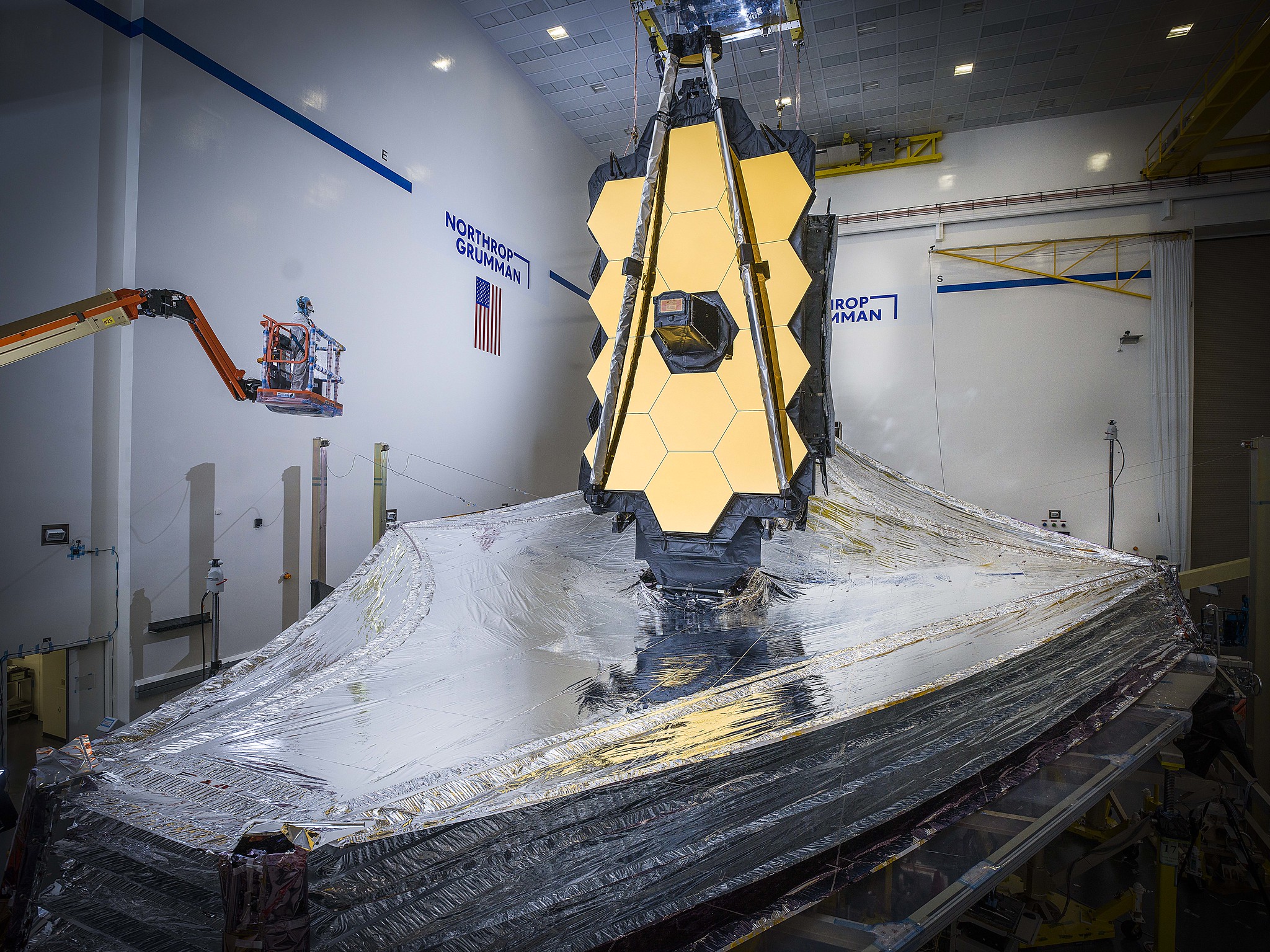

The Webb’s primary mirror comprises 18 hexagonal-shaped smaller mirrors arranged in a honeycomb shape 6.5 metres across, compared to Hubble’s spherical 2.4 metre diameter mirror.

“The bigger the mirror, the sharper you see. So, if you compare with previous space-based telescopes, this is obviously the biggest one. You have a very good view into the cosmos,” says Glauser.

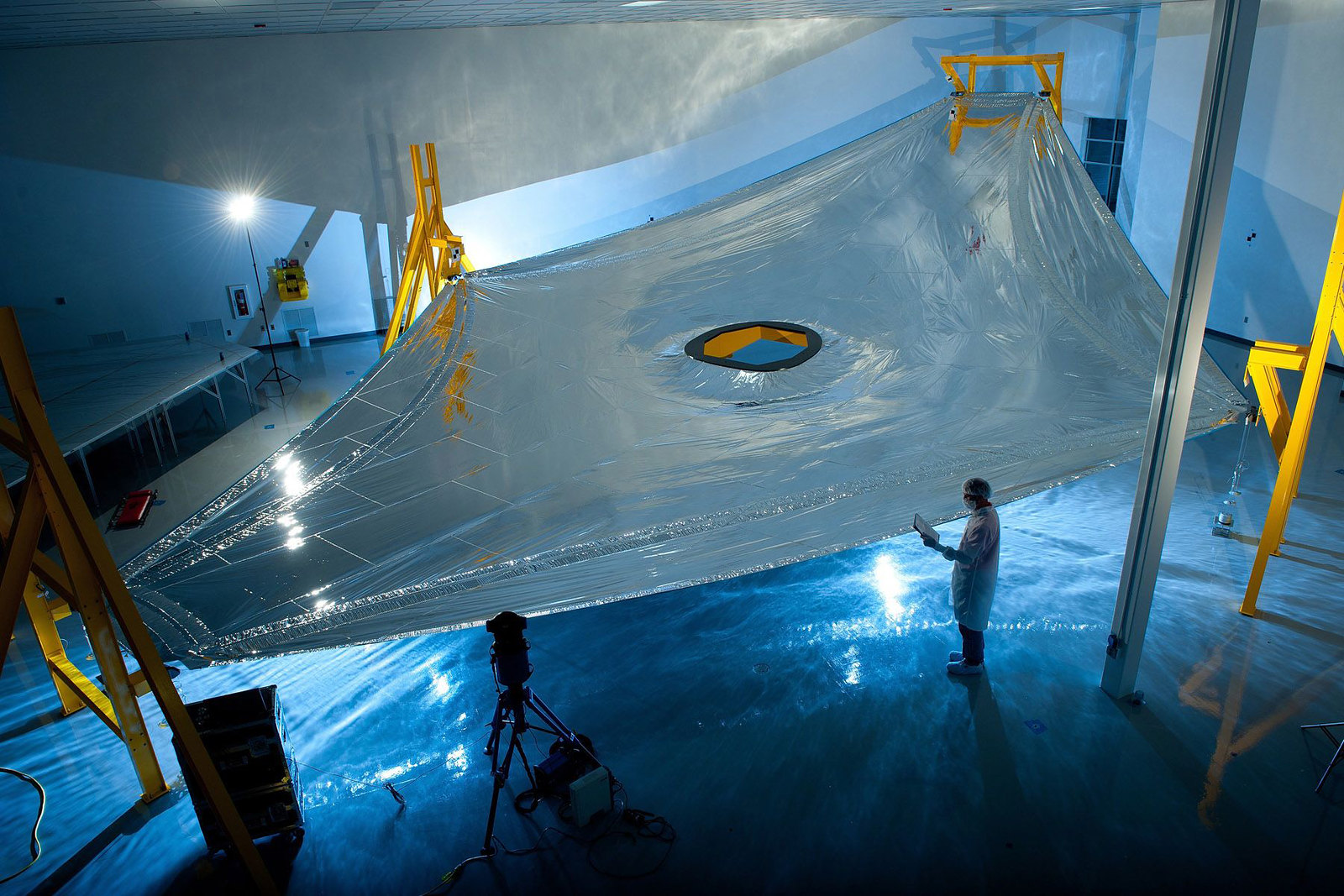

The Webb will be cooled and protected by a tennis court-sized sun shield made of five ultra-thin layers of a specially made composite material called Kapton.

Infra-red instrument

The telescope carries four science instruments. Swiss researchers, led by Glauser, contributed to the mission via their collaboration on one of these: the international Mid-Infrared Instrument consortium. They helped design and test certain components that were integrated into the instrument.

The job of the Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) is to look at the poorly explored infrared wavelengths from five to 28 microns instead of the 0.6 to five microns to which on-board “Near-Infrared” devices are sensitive. This will allow it to see the oldest, coldest and dustiest objects in the universe.

Building such an ultra-sophisticated sensitive instrument for cryogenic – very low temperature – conditions in space was “super challenging”, says Glauser.

“It is extremely demanding in terms of the engineering, the selection of materials and processes, and the testing, which meant many months of cryogenic cycling and operational mistreatment of the devices to ensure that they really are more robust than they have to be,” he explains.

“We had to develop quite a lot of specific things for what at the end looks rather simple.”

The detectors inside the telescope’s instruments that convert infrared light signals into electrical signals for processing into images need to be cold to work correctly. Typically, the longer the wavelength of infrared light, the colder the detector. MIRI’s detectors need to be at a temperature of less than 7 kelvin (-266 Degrees Celsius) to operate properly. The sunshield ensures they are cooled below 40 kelvin, but a helium-based “cryocoolerExternal link” – a sophisticated fridge – is needed to actively cool MIRI even lower.

First mooted in the mid-1990s, the James Webb Space Telescope was originally supposed to launch in 2004. But the telescope was held back by the fact that the technologies necessary for its deployment weren’t actually invented until 2007.

After many delays and cost overruns, the telescope’s original price tag has risen from $500 million in 1996 to $8.8 billion, with operational expenses projected to increase its total price to almost $10 billion.

“It was a very thorough test campaign. I haven’t seen anything similar before, where not only the spacecraft, but any integration step was tested on a mock-up. We did everything humanly possible to make sure this mission works. I think that also explains a little bit the high price tag,” said Adrian Glauser, an astrophysicist at ETH Zurich.

The Webb has been developed by NASA together with the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Canadian Space Agency (CSA). Swiss scientists have been closely involved in the project and some Swiss technology is on board.

As part of their “hardware” contribution to the NASA mission, Swiss scientists, together with RUAG Space, the Swiss technology group, developed a mechanism that protects and seals MIRI against external contamination during the cooldown phase after the launch. In addition, they helped build with the company Syderal cryo-cables used to connect telescope instruments and devices.

After the launch, Glauser will continue to monitor the Webb and MIRI for six months. As a long-term collaborator on the project, he will also have priority access to some of the first scientific results that get beamed back to Earth.

With the launch of this new telescope, space science is entering a new era, says Glauser. Scientists will be able to see much further in space and in time than the Hubble, right to the edge of the observable universe, he says.

“We will be able to really see the first galaxies that existed in the history of the universe. This really is quite something,” says the Swiss astrophysicist.

More

In space exploration, Switzerland punches above its weight

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!