New test targets anthrax threat

A Swiss research team says it has developed a simpler and more accurate testing system for deadly anthrax than those already in existence.

Scientists say the approach could be used in testing for anthrax spores, which are used in biological warfare.

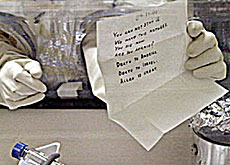

The last serious anthrax attack dates from October 2001, in the United States, in which five people died after contaminated letters were sent to political and media organisations. This flagged up the need for fast and reliable tests.

The Swiss researchers, from the Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, the Swiss Tropical Institute in Basel and Bern University, isolated a molecule unique to anthrax, which is found on its surface.

They used it to create an immunological test that gives accurate results in minutes. This is in contrast to more time-consuming and expensive genetic methods, said the team.

The research has been published in the online edition of the academic journal Angewandte Chemie [Applied Chemistry].

“An immunological test takes five to ten minutes to work and it’s very important that you get a quick response,” Peter Seeberger, an organic chemistry professor at the Federal Institute, who took part in the research, told swissinfo.

“If you are treated within the first 24-48 hours your chances of survival are good, if not your chances of dying are 95 per cent or greater.”

Difficult

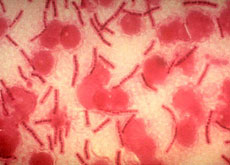

Until now it has been difficult to create a reliable immunological test – which detects a substance through its antibody-creating reaction with the immune system – because the spore cell surface of anthrax is too similar to those of other bacteria.

“Right now there are antibody-based systems being used in post offices in the US,” said Seeberger.

“The problem is that anthrax cell surface proteins and those of other closely related bacteria are identical so what you get from the tests are false positives – so it may be that a harmless bacterium is present but it gives you a positive readout.”

However, Seeberger and his team recently discovered a unique sugar on the surface of anthrax spores.

As isolation from the deadly bacteria was not possible, scientists had to recreate the substance from scratch.

The molecule was then attached to a special carrier protein and injected into mice. The rodents’ immune systems reacted, producing antibodies which were specific to the surface molecule.

Basis

Seeberger hopes that the new antibody will be the basis for a highly sensitive anthrax diagnostic system and also for new vaccines.

“I think it would be very useful and it could be important for testing against biowarfare,” said Seeberger.

The system could be used by the authorities, post offices and medics responding to potential anthrax threats, he added, as well as by armies in the field.

He added that the antibodies could be plugged into existing systems and that this might take about six months.

Seeberger said the team was already in discussions with interested companies. He hopes that the work can be done in Switzerland, but says it might be done in the US.

swissinfo, Isobel Leybold-Johnson

In recent years concerns over biological warfare have been mounting and Switzerland has stepped up its efforts to protect civilians against a possible biological terrorist attack. It has established a crisis centre to deal with any such incident.

Anthrax is normally found in domestic and wild animals but can be transmitted naturally to humans. It is, however, rare in European and North American countries.

In Switzerland there have been only two recorded cases in the last 20 years.

Anthrax is an infectious disease caused by a spore-forming bacterium – Bacillus anthracis. It normally affects wild and domestic animals such as goats and sheep.

It can infect humans in three ways: through inhaling anthrax spores, by eating infected meat that has not been cooked sufficiently and by absorption through the skin.

Signs of the disease usually appear within three days, but in some cases it can be up to two months.

Antibiotics can cure the disease but they must be administered quickly. Vaccines exist for most strains.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.