Cern hopes to find “God particle” by 2012

Scientists at the European Organisation for Nuclear Research (Cern) expect to discover – or disprove - the existence of a key particle in Big Bang theory by 2012.

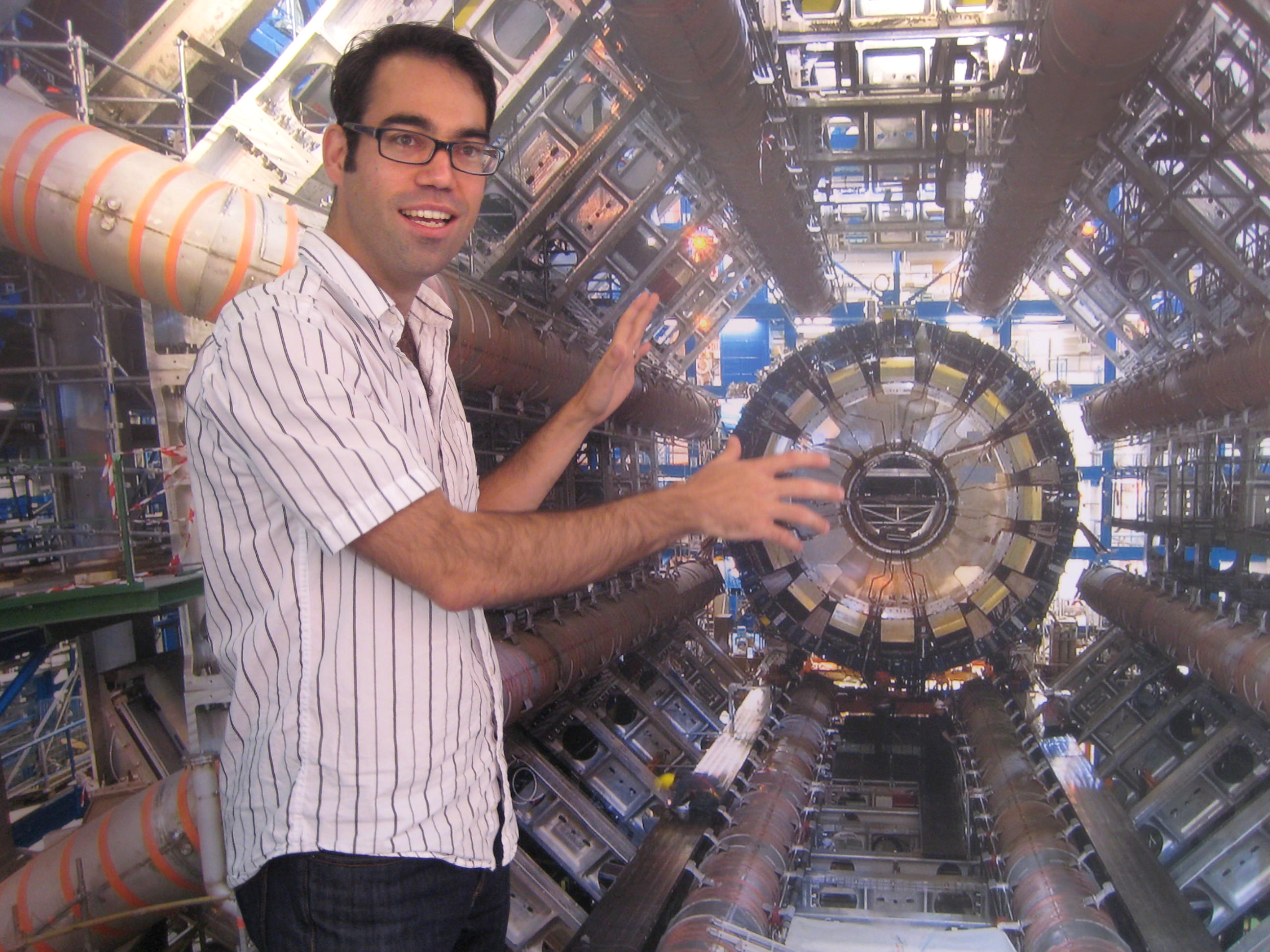

Cern director Rolf Heuer says the latest findings from the world’s most powerful particle accelerator, the Large Hadron Collider, have been enough to convince the centre that progress is being made in their hunt for the most sought-after of particles – the Higgs boson.

“I would say we can settle the question, the Shakespearean question – ‘to be or not to be’ – end of next year,” he told reporters at a major conference in Grenoble, France on Monday attended by around 700 leading particle physicists.

Sometimes referred to as the “God particle”, the Higgs boson is the linchpin of the Standard Model of particle physics theory on the Big Bang. It is believed to give mass to other objects and creatures in the universe.

“They have tested the Standard Model very well,” Heuer said of Cern scientists. “They are now ready to bring us into uncharted territory. We are still missing the most wanted particle, the Higgs boson.”

These are “exciting times” for particle physicists, he noted, because of recent findings by two separate teams of scientists at Cern.

Understanding the universe

There are six experiments around the 27-kilometre circular Large Hadron Collider deep under the French-Swiss border near Geneva.

Last year, the collider for the first time threw together two proton beams, tiny particles traveling in opposite directions though the tunnel at incredible speeds in conditions simulating those one trillionth to two trillionths of a second after the Big Bang.

The crash on a subatomic scale is aimed at improving knowledge of how the universe was created billions of years ago.

The power produced has been ramped up to ever-new record levels this spring, creating reams of new data for analysis, and scientists are starting to pinpoint the precise level of high energy where the Higgs boson is expected to be found.

Only by the end of 2012 will the particle collisions be large enough. When it is running at full capacity the collider will produce 20 times more collisions than today.

“Considerable excitement”

The $10 billion (SFr8 billion) machine got off to a problematic start over three years ago. Nine days after its inauguration, the project was suspended when a badly soldered electrical splice overheated, causing extensive damage to the magnets and other parts of the collider some 100 metres below the ground.

It cost $40 million to repair and improve the machine. Since its restart in November 2009, the collider has performed well and given scientists valuable data – enough to make up for lost time, according to Heuer.

“The amount of data gathered to date is equivalent to what was predicted for the whole of 2011,” Heuer added.

Fabio Zwirner, a physicist at Padua University, Italy, said there was “considerable excitement because of the many new results” at the conference, but physicists were still unsure whether they were seeing “hints” at finding the particle, or were running into statistical errors.

Physicists also hope the collider will help them see and understand other suspected phenomena, such as dark matter and antimatter.

Physicists once thought protons and neutrons were the smallest components of the atom’s nucleus, but colliders showed they are made of quarks and gluons and that there are other forces and particles.

Should the Higgs boson fail to be detected, some physicists think the field will then become even more interesting, as they will be forced to revise Standard Model theory.

The collider took about 15 years to construct.

It is 4.5 times longer than the Tevatron in Chicago, once the largest particle accelerator, and has about 50 times more energy stored in its beams.

An estimated 10,000 people from 60 countries have helped design and build the accelerators and its massive particle detectors.

The LHC, which currently operates at 3.5 trillion electron volts will be upgraded in 2013 so that it can run at seven trillion volts, starting in 2014.

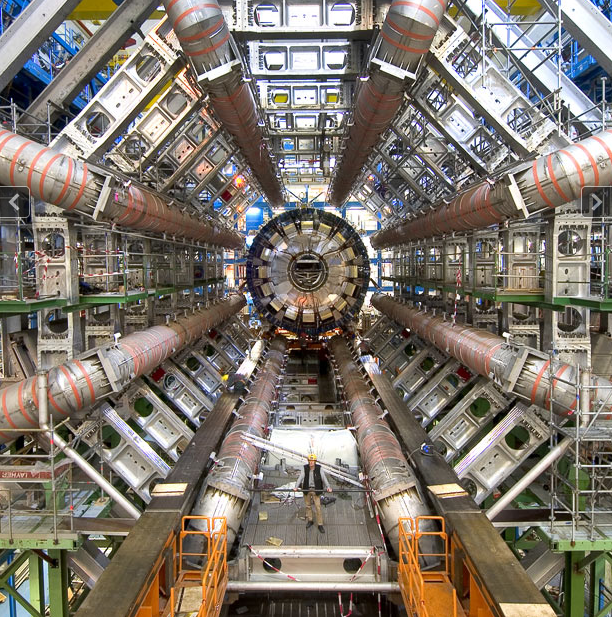

In the Large Hadron Collider, high-energy protons in two counter-rotating beams are smashed together to search for exotic particles.

The beams contain billions of protons. Travelling just under the speed of light, they are guided by thousands of superconducting magnets.

The beams usually move through two vacuum pipes, but at four points they collide in the hearts of the main experiments, known by their acronyms: ALICE, ATLAS, CMS, and LHCb.

When operational, the detectors see up to 600 million collision events per second, with the experiments scouring the data for signs of extremely rare events such as the creation of the so-called God particle, the yet-to-be-discovered Higgs boson.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.