When housing shortages sparked riots in Switzerland

Housing shortages first became a hot topic in Switzerland in the second half of the 19th century. At the time, the issue was referred to as the “workers’ housing question”. It presented a challenge to municipal governments and even led to riots.

In the second half of the 19th century, people’s day-to-day lives underwent rapid change. It was an age of upheaval, as reflected in the title of a key reference work on the changes occurring at the time – ‘Das Neue kommt’ [‘The new is coming’]. The advent of railway was an innovative and influential triumph. So too was industrialisation. Steam power and electricityExternal link made it possible to set up and operate factories in locations where there was no hydro power, which is what early industrial production had relied on.

SWI swissinfo.ch regularly publishes articles on historical topics curated directly from the Swiss National Museum’s blog pageExternal link (available in German and often French and English).

The momentum of industrialisation caused towns and cities to grow. And the growth accelerated, as shown by the figures for Basel: it initially took 70 years for the city’s population to double up to the mid-19th century, another 30 years for it to double again, and just the last two decades of the 19th century to double for a third time. Meanwhile, the city of Zurich grew by 9,400 people every year between 1893 and 1897 – the period when the Swiss National Museum was being built. That equates to a growth rate of 7.3% and is six times higher than the city’s current rate of growth. Nationwide, the urban population grew sixfold between 1850 and 1910. In no other census period was urbanisation as strong as between 1888 and 1900.

Migration to towns and cities – initially from rural areas of Switzerland and later also from abroad – placed an excessive burden on the construction industry and overwhelmed the housing market. There was not enough affordable housing for all the people who had come to the cities to work. Most of the buildings under construction were profitable prestige, commercial and factory buildings, as well as villas and upmarket residential buildings.

The City of Basel’s official records from 1891 state: “We are seeing that in certain towns and cities there is a surplus of upmarket housing, and at the same time, an extreme shortage of housing for ordinary people. Developers are building homes to sell rather than for long-term letting.” And Zurich City Council noted in its 1897 annual report that there were only 7,785 affordable rental dwellings for 25,000 low-income households.

In short, there was not enough housing for workers and their families. But the housing shortage was not only in cities, it was also in small towns like Arbon, which saw rapid expansion at the time, primarily due to the strong growth of the companies Saurer and Heine. Housing was even a problem in rural areas, such as the lower Reuss valley in the canton of Uri, which, after the opening of the Gotthard railway, became a well-connected and therefore attractive location for industry.

Night lodgers and boarders

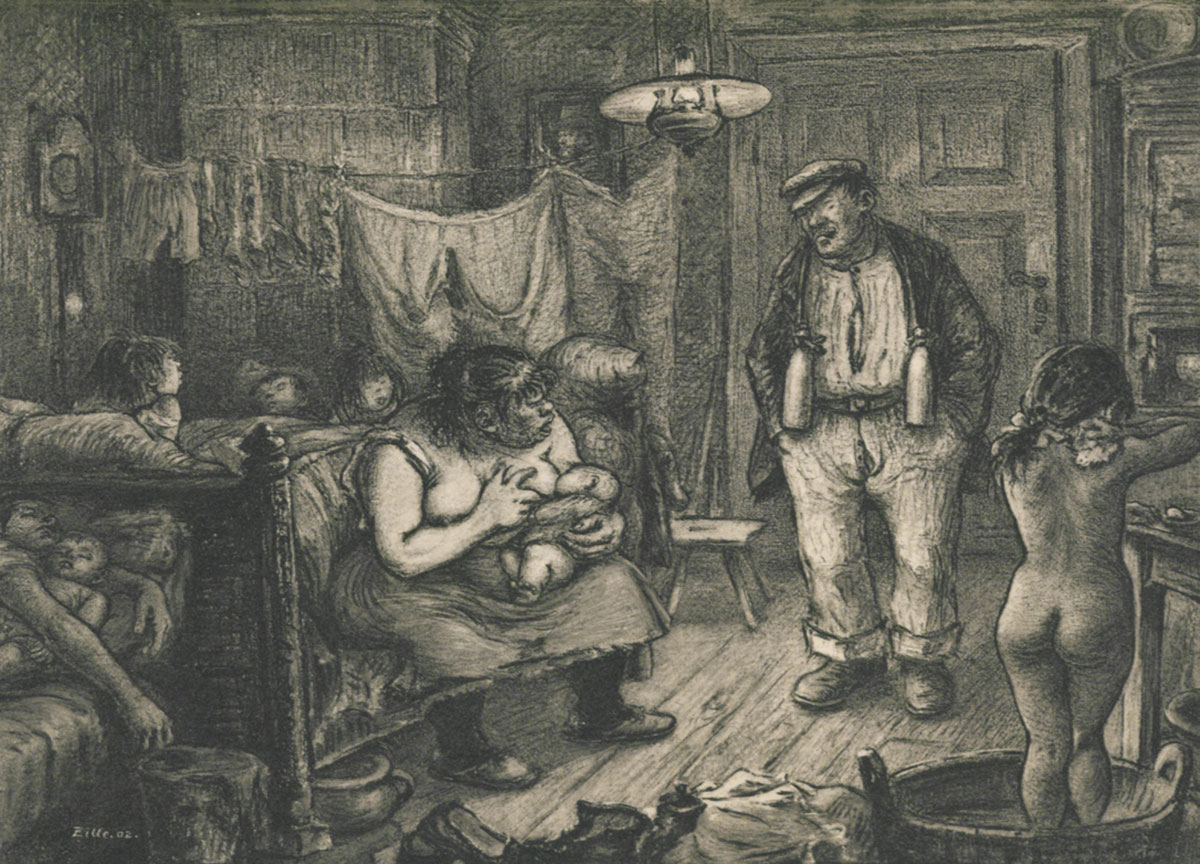

And the same thing was happening everywhere: the available rental dwellings were divided up, extended, and every last square metre was let, from the cellar to the attic. And prices for these cramped, dark and poorly ventilated dwellings were eye-watering. Official surveys show that the rents for such dwellings exceeded those of luxury apartments in cubic metre equivalents. So the smallest homes were actually the most expensive.

To be able to afford the high rents, many people took in lodgers to live in specially separated parts of their homes. Or they accommodated so-calledSchlafgängerExternal link, or ‘night lodgers’ to whom they would rent out a bed in their own room, sometimes in eight-hour shifts. For a time, lodgers and Schlafgänger made up over 15% of Zurich’s population. And there were always homeless families in Zurich and Bern who were forced to sleep in barns, stables, attics and under bridges.

Public debate

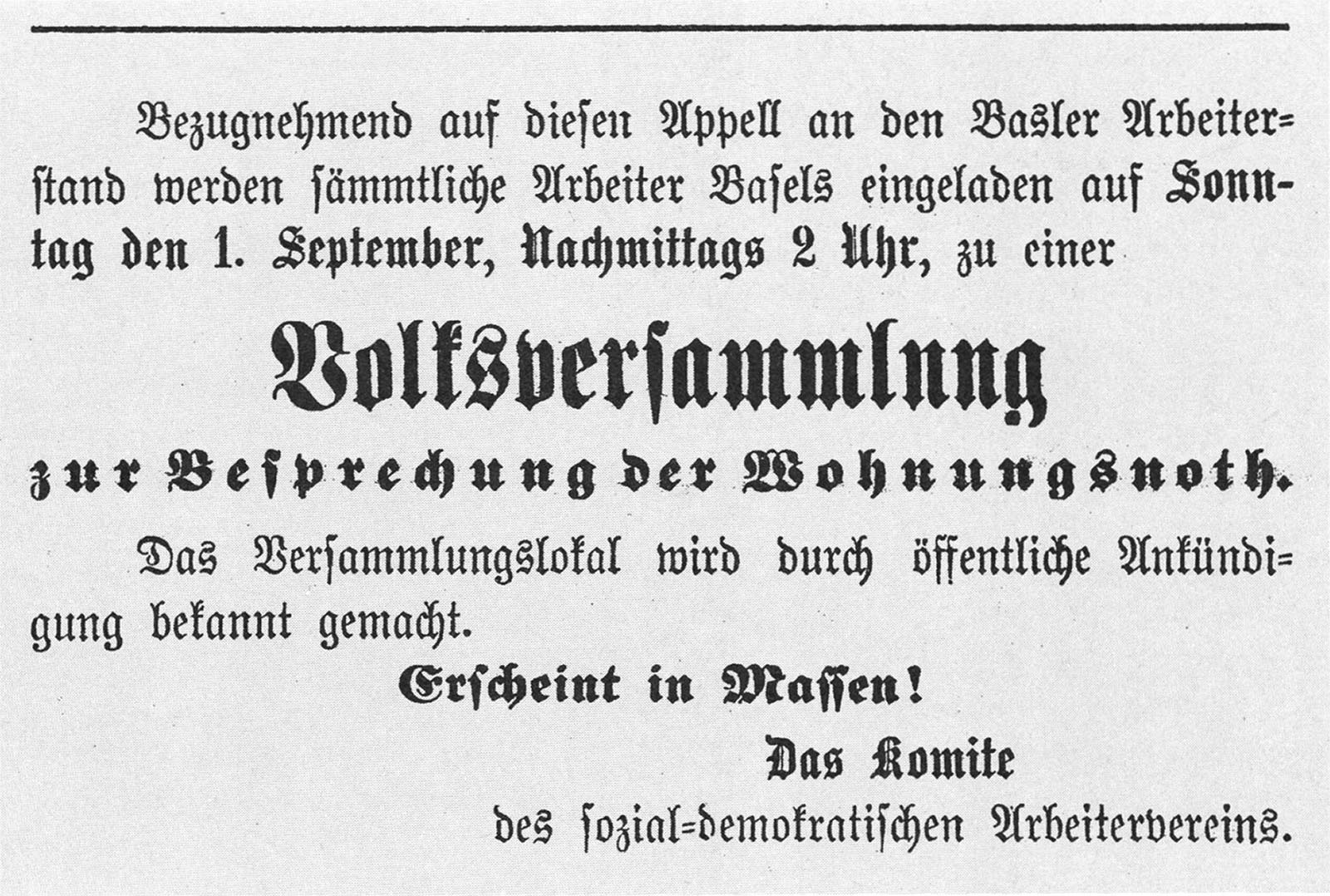

Housing conditions featured increasingly in public debate – both in Switzerland and in other countries, where the same picture emerged in many towns and cities. In 1872, Friedrich Engels devoted a series of articles to the housing question. The same year, a committee of the Social Democrat workers’ movement in Basel called for a people’s assembly “to discuss the housing crisis”. There were calls from all sides to take a closer look at the housing situation.

Starting in 1889, the cities of Basel, Lausanne, Bern, Zurich and Lucerne carried out so-called ‘Wohnungsenquêten’. These time-consuming and costly surveys sought to assess housing conditions based on rigorous scientific criteria. The results documented for the first time the scale of the housing crisis and finally placed the matter on the political agenda as the “workers’ housing question”.

Before the survey in Zurich was completed, the City Council recorded in its annual report for 1894: “Numerous on-site observations have led us to conclude that the question of workers’ accommodation has reached a stage that is likely to cause a public outcry.” The City Council appeared concerned as to whether the “overcrowding” of dwellings, “which was already resulting in the most severe health, moral and social effects would inevitably become even worse if far-reaching and resolute action was not taken to counter the scourge that threatened to become chronic”.

According to the City Council, conditions would not improve but only deteriorate, “if housing provision was left to its own devices, i.e. property developers, and if society and employers did not intervene to regulate the housing situation in the public interest”. Zurich City Council decided to “set up a committee from among its members”, “with the task of carrying out a thorough examination of the issue of workers’ housing”.

No initial tangible results

There were no tangible results in the first few years, however. The deliberations on a series of applications “dragged on for various reasons”, as noted by Zurich City Council. One of the reasons was an economic slump, which caused the city’s growth to temporarily slow down. However, political circumstances are likely to have also played a part. The working class still had little political clout shortly before the turn of the 20th century. But from 1900 onwards, the Social Democrats were the most powerful party in Zurich’s parliament. The following years saw the first housing development project materialise (Limmat colony, now Limmat I housing estate), which was then adopted in a popular vote in 1907.

In 1896, the cantonal government and parliament in Basel clearly rejected the idea of delegating the construction of cheap rental housing to the public sector. The first projects for the construction of housing by the state only materialised there in April 1919 and in September 1921. Elsewhere, for example in Arbon, where the electorate approved a subsidy to the local public building association in 1907, the public sector was involved in housing construction projects, which were driven by private actors. Or industrial firms themselves built housing for their workers, for example Rieter in Winterthur. While individual housing cooperatives emerged as early as the mid-19th century, they were usually short lived. It was not until after the First World War that they met with a favourable political and financial environment.

Strikes and conflict

The poor housing conditions in the second half of the 19th century played a significant part in the hardening of the social climate at the time. One of the main proponents of this position was Bruno Fritzsche, the professor at the University of Zurich’s Research Center for Social and Economic History, who died in 2009, and who with his team wrote the social history tome ‘Historischer Strukturatlas der Schweiz. Die Entstehung der modernen Schweiz’External link.

The housing shortage – as well as the issue of wages – was not only one of the main reasons behind organised strikes, but also a series of conflicts “that broke out because of ‘trivialities’ and ‘petty matters’ without any plausible or concrete demands.” Examples of such conflicts are the Käfigturm riotsExternal link of 1893 in Bern, the Italian riotsExternal link in Zurich in 1896 and the Arbon riotsExternal link of 1902. Fritzsche argued that the question of workers’ housing was much more important than workplace conditions in the emergence of labour organisations, class consciousness and ultimately the class struggle.

Guido Balmer is communications manager at the city of Fribourg’s department for territorial development, infrastructure, transport and environment. He is also an independent communications professional.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.