Didier Calame: an organic farmer on the political right goes to Bern

The surprise election victory of Didier Calame to the federal parliament marks a comeback by the agrarian wing of the right-wing Swiss People's Party. The farmer from western Switzerland intends to advocate for green agriculture, but also for growth in the sector.

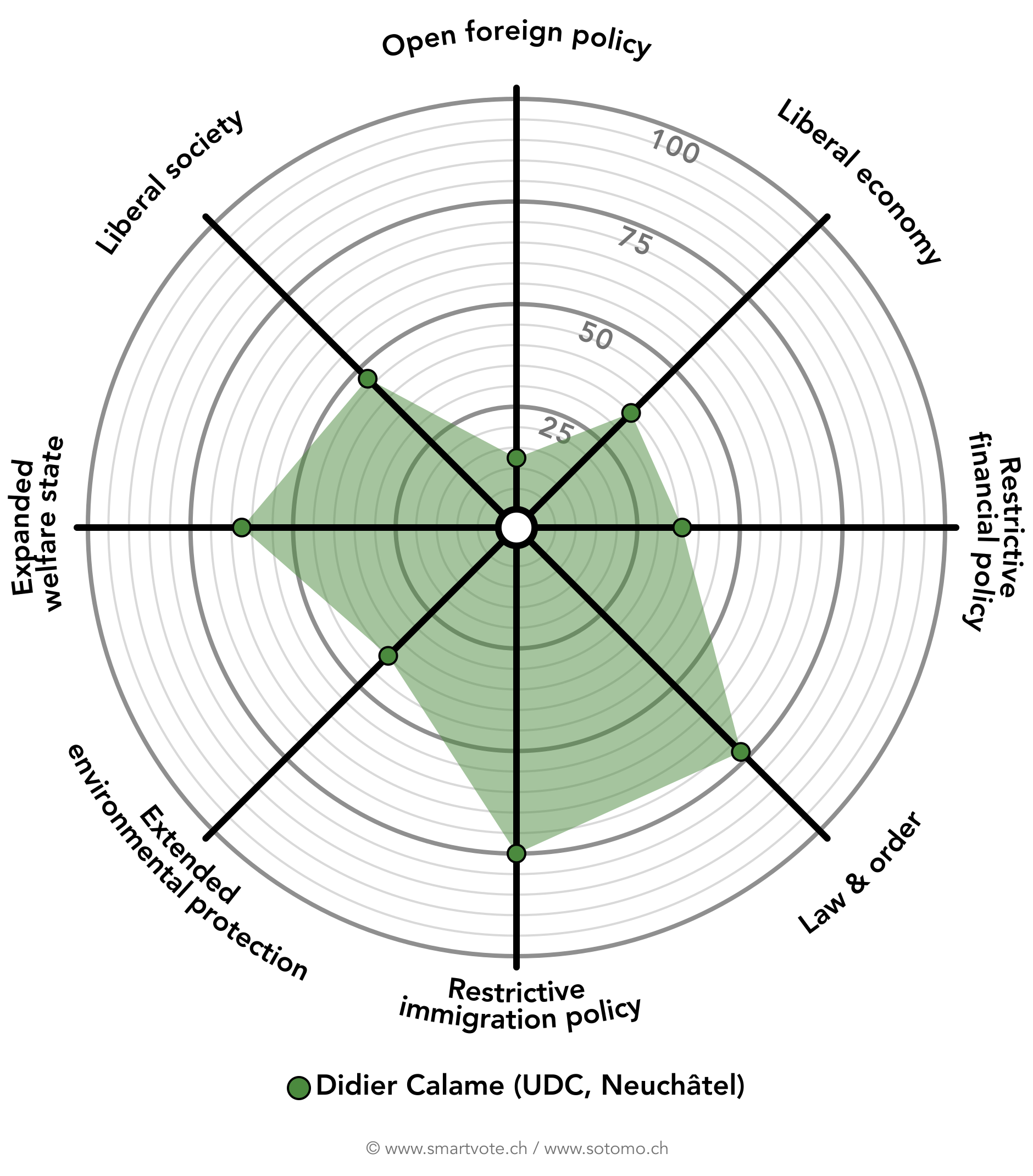

“I’m a countryman.” This is how Didier Calame describes himself. He is the new Swiss People’s Party representative for canton Neuchâtel in the Swiss parliament.

With his straight talk, the organic farmer, who also runs a sanitation business, plays the authenticity card. At his farm in Les Planchettes, a village near La Chaux-de-Fonds, the 51-year-old welcomes SWI swissinfo.ch to his office, located above the barn which houses about 100 animals, as he puffs on a cigarillo. “I’m still the same person I’ve always been”, he declares.

Last October, Swiss voters chose 56 new representatives to join the federal parliament in Bern. The Swiss People’s Party, the Centre Party, and the Social Democratic Party made the biggest gains in the 2023 election and sent the greatest number of new faces to parliament. The Green Party, on the other hand, suffered heavy losses and sent no new representatives to Bern.

In this series, SWI swissinfo.ch profiles some of these new parliamentarians as they take their first steps in federal politics.

Simplicity was also the main feature of his election campaign. “For the posters, we took photos of me with my cows, using a smartphone. The whole thing was finished in a quarter of an hour,” he recalls. He did decide to start a Facebook account for the occasion, “with the help of a friend – I still belong more to the paper world than to the electronic world,” he says.

It turned out to be a winning formula. His election meant the Swiss People’s Party in canton Neuchâtel regained the House seat it had lost in 2019. It still came as something of a surprise, says Adrien Juvet, editor-in-chief at BNJ FM regional radio.

“Many people did not expect to see Didier Calame reach such a convincing score,” says Juvet. “His success was due to the grassroots campaign he ran. He knew how to talk to people and get his message across.”

Calame himself hardly expected to win a seat in parliament. On the Sunday of the general elections, he was travelling to a shooting competition when he got an urgent summons to Neuchâtel, as the vote was going his way.

Calame says that of course, he did hope to win: “At the age of 51, I wasn’t doing this just to be a token candidate.”

The election of this Neuchâtel native son is symbolic of the comeback of the agrarian wing of the People’s Party, which was eclipsed in the early 2000s by the surge of the hard-right, anti-immigration wing led by party strongman and former justice minister Christoph Blocher.

“I am a man of compromise, capable of talking to my political opponents. People like that,” says Calame, who identifies himself as being “on the left wing of the People’s Party”.

His openness is appreciated across the political divide. “Didier Calame is a low-key sort of person. I am getting to know him better now, although I was also a colleague of his in the Neuchâtel cantonal parliament,” says Green Party member of parliament Fabien Fivaz. Despite their political differences, Fivaz thinks he can work with Calame. “He is calm, thoughtful, and not at all extreme,” he says.

An organic farmer, minus the clichés

Fivaz believes he could find common ground with the mountain farmer on issues regarding agricultural policy. “The Greens are also in favour of small-scale farming and promoting buying locally. Yet I would assume that Didier Calame doesn’t do organic agriculture just for the love of nature, but for economic reasons as well,” he says.

“Fabien Fivaz is mistaken – I don’t make more money doing organic farming,” says Calame of his livestock operation. He gets CHF200 ($228) more in direct payments from the government per hectare of land each year since he decided to go organic in 2015.

Yet this amount is not enough to cover the extra costs involved, he says. “Today, the incentives to produce in a green way are not enough,” he says. “You need to be really convinced about preserving the land.”

Calame is not “one of those organic farmers with long hair and a knitted pullover,” as he put it in an interview with the farming magazine Schweizer Bauer.

He explains that his vision differs from that of the Greens, because he favours aiming for maximum yield in agriculture. “I use big machines. I use organic fertilisers,” he says. “I get the most out of my farm – not like a hard-core environmentalist who would be willing to get less out of it.”

Agriculture as a priority issue

His vision of agriculture will be at the heart of his political activities in Bern. “I’ve decided to concentrate on what I know best,” he says.

Calame will fight to keep the farming budget stable “so that farmers will not be compelled to produce less. The idea is all very good, but the problem is that the prices are not keeping up,” he says. He accuses the major retailers of making a tidy profit while the producers, forced to accept low prices, see their incomes declining.

In his view, it is also crucial to limit constraints and bureaucratic rules being imposed on the world of farming. “We certainly do need rules. But the situation has got out of hand. A farmer now spends more time filling out forms to document his activities than he spends actually doing them,” he says.

He concedes that Swiss farmers are better taken care of than their European neighbours. Although he understands the exasperation that has led EU farmers to protest in the streets, he doesn’t think that such large-scale demonstrations would have been justified in Switzerland.

“We get more state aid, and we are not as exposed to the fierce competition from countries in Eastern Europe, which export huge amounts of low-priced produce to the EU,” he says. To protect Swiss farmers, he advocates this country keeping its distance from the European Union.

Commitment in his blood

Calame is a committed politician to the core. He may still be in the process of familiarising himself with the byways of federal politics, but he can count on some solid experience. He started in politics at the age of 24, when he was elected to the local council in his native Les Planchettes, before being elected to the executive, where he still holds office.

He started out as a member of the centre-right Radical-Liberal Party. When a Neuchâtel branch of the People’s Party was founded, he had no hesitation in joining.

“It was opportunism on my part, because I was more likely to get elected to the cantonal parliament of Neuchâtel if I was with the People’s Party,” he admits. This strategy paid off, as he succeeded in getting elected to the parliament of his canton, and held the seat for 15 years.

“Getting elected to the national parliament is the cherry on top in my political career,” he says with satisfaction. His ambition doesn’t stop there, though: “I am a man who wants executive responsibilities.”

Will his next stop be a ministerial portfolio in the federal government? It’s too soon to be thinking about that. “I will do my best with my mandate for the 2023-2027 legislature, then hopefully be re-elected,” he says, without entirely closing the door on a future role in government.

His family already produced one federal cabinet minister. Pierre Aubert, who served in the government from 1978 to 1987, was his grandfather’s cousin. Calame is keen to pass on his interest in public life to his three children. “My 17-year-old daughter is interested in politics, but she is more to the left than I am,” he notes. He could see her in the Green Party, which is already producing a few lively discussions at the dinner table.

Work as a core value

Calame is living proof that social mobility is possible in Switzerland. He does not hide the fact that he never finished his apprenticeship in agriculture. “At 16, I left home to do that but I was too homesick,” he says. “My father let me quit and come home, as long as I found a job. That’s what I did.”

Work is a core value in his life: in addition to holding political office and his occupation as a farmer, he has a second income-generating activity as the owner of a business sanitising sewers and drains that employs several people. “Even if I suddenly became a millionnaire, I wouldn’t stop working,” he says.

His time is so limited that he has to manage it carefully in order to attend parliament in Bern. “When I am in Bern, I delegate everything to my employees so I can concentrate on politics,” he explains. “But when I’m here, I’m the boss.” He has had to give up some hobbies: “I will hardly have time to practise shooting any more.”

He is too attached to his native soil to be able to think of ever living abroad. Calame himself has little connection to the Swiss Abroad. Yet in parliament, he intends to support the introduction of electronic voting to make it easier for the diaspora to exercise their political rights. “Even if they’ve left the country, the Swiss Abroad should be able to have their say on what is going on here,” he says.

What about the idea of eventually retiring to a far-off sun-spot? The idea doesn’t much appeal to Calame. “I have all I need here,” he says, even though he sometimes thinks of acquiring a holiday home in the Aubrac region in central France, and spending a few months of the year there. “I love that region”, he says. “That’s where my cows come from.”

Edited by Pauline Turuban and Samuel Jaberg. Adapted from French by Terence MacNamee/gw

Do you want to read our weekly top stories? Subscribe here.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.