“We were transported to shore by the lice”

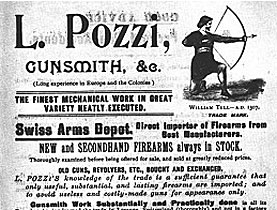

Leonardo Pozzi, in common with many Ticino emigrants, exposed the false promises of the shipping agents in his letter home.

Despite the appalling conditions on board the ship, Agen Heinrich, Pozzi survives the long journey from Hamburg to Melbourne following the route around the Cape of Good Hope.

Life on board is “barbarous”, according to Pozzi. The food is barely edible, the sleeping quarters are no better than “stables” and the captain is denounced as a “trader in human flesh”.

Melbourne, 24 September 1855

Dearest mother and all at home!

Now that God has brought all five of us from Giumaglio to our destination, and we have finally arrived in this beautiful city with our other compatriots safe and sound, apart from those I shall tell you about, we can give you news of our perfect state of health and readiness to set off for the mines, especially given the hopeful news we have from the citizens of Melbourne. Yesterday I received a letter from Alessandro telling me that the mines are still going on as before, with some doing well and others not, and that this winter they didn’t achieve much but are still hoping to make a fortune, as many are doing, and that they are in very good health, as are the Sartori cousins and the Bonetti brothers.

Oh, how long a tail gold has! Through patience we have at last got hold of the end of it. But who knows how long it will take to get possession of the beast itself. I hope the beast will require less patience than the tail because, when I give you details of the voyage, you will understand what a miserable time we had of it, and not so much ourselves as the other passengers. Let me tell you in general how barbarously we were treated.

This is the story

We left Hamburg on 31 May with a bark or ship named the Agen Heinrich, under the command of Captain Oldejans (who looks very much like Pietro Vanoni), and arrived in Port Philip on 19 September. There were 169 of us, including the sailors, and three from the Valle Maggia who died: Giacomo Guglielmoni , son of the late Carlo Giov. of Fusio, living in Niva, who died on Monday 3 September, aged 55; Giuseppe Filippini from Cevio, died 6 September, aged 31; and Antonio Baroggi, son of the late Giov’ant, aged 27, who died on 13 September, from Cerentino.

Musci and Guerra and his boy are here with me. Musci did not even suffer from seasickness. In all, there were 172 passengers on board: 2 from the Val Verzasca, 120 from the Valle Maggia, 10 from Lugano, 8 from Piedmont, 15 Germans and 13 sailors including the captain, two pigs (which makes 15) and two dogs (which makes 17). The ship was 56 ells long and 12½ wide with three masts. The main mast was 28 ells high and ¾ in circumference, the second 26 and the third 21½, measured from the top to the deck for going down into the saloon. The voyage from Hamburg to Melbourne took 2,600 hours.

So on the 19th we arrived in Port Philip and there the health police came to inspect the passengers, because they are very strict, and took off seven sick people from the Valle Maggia to take them to the right of the channel, where they won’t have to pay anything. There were two of the young Pedrazzis from Cerentino, a certain Antognoli, son of the bailif in Cevio, another from Cevio called Damonte, the school teacher Rottanzi and a lad from Cerentino. On the 21st we arrived in the port of Melbourne at six o’clock in the morning and waited there until four o’clock in the afternoon of the 22nd. The captain did not want to let us go unless we gave him a certificate of good conduct, but none of us wanted to do so, so after 48 hours he had to let us go. From there, we arrived in Melbourne itself on the evening of the 22nd, taking a steamboat to go up river to Melbourne, which takes 5 or 6 minutes.

It was written…

The voyage would be bad enough (or so I believe) if you were treated well, worse if you are treated badly. Compare the contract and what we actually received. It was written that we should have 5 pounds of bread but it was never given, 7 ounces of butter, 5 ounces of sugar, 4 or 5 ounces of cooked meat a day, 5 pounds of biscuits a week. In fact, in the morning there was black coffee (so called); in the evening, tea. With this we ate our biscuit. (Gioan often told me that tea and that coffee was excellent for washing [on] the second of August). At midday on Sunday, we had meat, what little there was cooked in seawater and always so raw that I could never eat more than a third of it, and “pudding” (a kind of dough, made rather like bread but softer; they put plums in it, then put the dough in bags to cook; and when it is cooked, they flavour it with the syrup. Monday: peas cooked in fresh water; to flavour it, they washed the meat with saltwater after cooking it and put two thirds of it in with the peas to make it into a minestrone, a pasterucco. Tuesday: beans prepared in the same way. Wednesday: rice, again cooked in the same way, which was the best of all. Thursday: sauerkraut, cooked the same way as the peas. Friday, cooked only with syrup because they did not give us any meat, instead they gave us some stinking fish called herrings; we had to wash them and eat them with vinegar, but I never did. I ate a lot of biscuit, which I liked although it was dry and sweetened with salt. Saturday: peas again.

Swindling Mr Müller

The most esteemed, reverend and swindling Mr Müller had the gall to enlist passengers with the lying promise that he had a ship equipped especially for passenger transport, and that it was possible to buy everything in case of need. But now I can tell you he is a real trader in human flesh. Below decks, the ship could best be compared to a stable, though at least a stable has light. But it was hell for the poor devils accommodated there (in the dark), even to be seated. When the sea was rough, many of them had to eat in their beds. The ceiling was a temporary structure of boards, but the ship was strongly built, able to face the waves. Up above, we were better off. It was like a room where we were, but overcrowded. I was able to arrange for Michele, Carlo, Giuseppe and Giovanni to be up above. We did not suffer at all. On the contrary, Giovanni, Carlo and Giuseppe are fatter than when we left, Michele and I much as we were. We found a way of making a soup out of our biscuit and tea and coffee, and adding butter to melt in it. We found this soup excellent. It didn’t do us any harm and we filled our bellies with it.

Giovanni had a hard time in June, being seasick the whole month. Giuseppe spent two days vomiting, then he was alright, as was Carluccio. And Michele and I did not suffer much either.

Four in a bed

We slept 4 in a bed. The beds were like one of those tables used for rearing silkworms. The sea was really rough when we crossed the Equator. We did not see the Cape of Good Hope. On the ship you couldn’t buy anything for love nor money. We managed to get them to make pancotto with the biscuit, giving everything for two months, three times a week. In second class, you get the same things as in third, but I always had more sugar, butter and everything. But what use was the cooked food? I could eat only a little of it, and the rest I gave away.

We often saw ships before we reached the Cape of Good Hope, few thereafter. When the winds blow across the boat, it sails better than with a following wind; and when the wind comes from head on, it sails on just the same, in a zigzag pattern. The only woman was one from Cevio. The food was not of poor quality, but not properly cooked. The sailors kept watch all night. My beret was blown into the sea from the top of the main mast. Musci would advise his son not to come because he fears he would fall sick on the ship. How I longed to have some cheese to eat with the biscuit and in the minestrone, and some spirits to drink at least three times a week. We saw a number of big fish.

Lack of language

If anyone is leaving, please send me in a letter a copy of the recipe for lime distemper you will find in a little book among my personal effects. Please, Celestino, copy it out just as it is. The ounces are given in letters, not numbers. At the beginning, you will find a little alphabet of numbers and letters. The book is printed in German script. Please copy out the other distempers, too. Please be careful with my things. From the ship, we were transported to shore by the lice! If you want to stay healthy on the ship you have to be very careful how you eat. At the Cape of Good Hope, we did not take on fresh water. Many ships were overtaking us. Here in Melbourne, we found the Bonaventura Lanfranchi, which had come to town from the mines. I heard that several of those from the Valle Maggia have returned home. Now I think I’ve told you everything, but I’m sure to have forgotten something, because I am so dull-witted I don’t know where my head is, what with the various inconveniences. We managed to find out where to get our money for living here in Melbourne, despite our lack of language. There are 30 people with me here.

I’ve heard that Giuseppe Righetti (“Pep”) has come here from California. Those who are fearful should stay home because the sea is always rough and it is easy to fall sick. We are all off to the mines. Meanwhile, we greet you and I remain your affectionate

Leonardo

The Pozzi correspondence is taken from the two volumes on the migrations of Ticinesi to Australia (L’emigrazione ticinese in Australia) by historian Giorgio Cheda, and reprinted with his kind permission.

One of the main reasons so many people emigrated to Australia was the “hard sell” of the shipping agencies. A “comfortable” passage cost between SFr450 and 1,200 at a time when a manual labourer earned little more than a franc a day.

Here is a translated extract from a newspaper advertisement: “During the voyage, passengers receive food of excellent quality, in accordance with the legal provisions in force at the port of embarkation, with three meals served each day. The dormitory is perfectly ventilated and healthy; first-class berths are furnished with every convenience, and perfect cleanliness is maintained on board”.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.