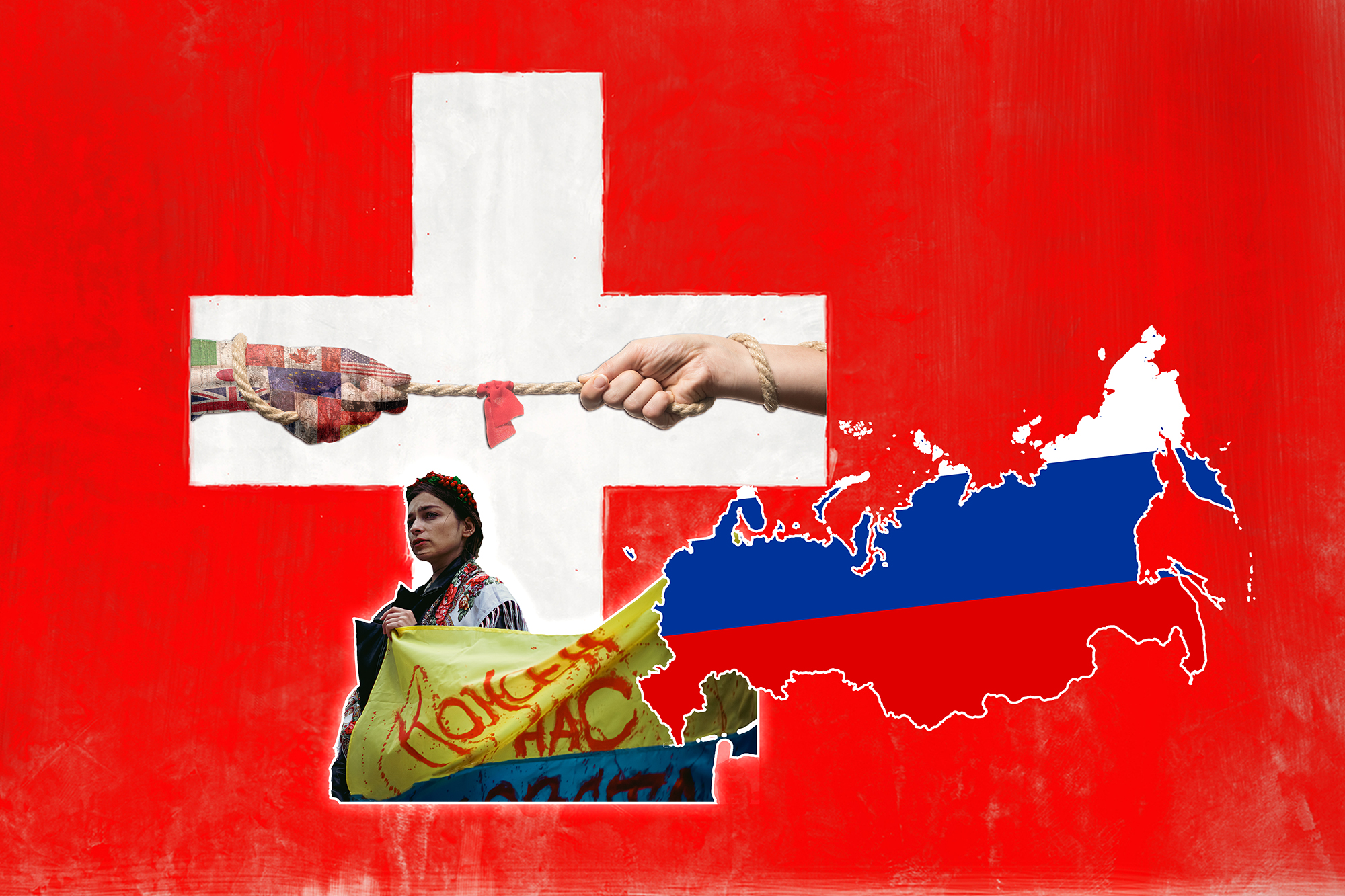

Despite criticism, the Swiss say they’re model enforcers of Russia sanctions

Switzerland is implementing sanctions against Russia for its invasion of Ukraine in an exemplary manner. So says Erwin Bollinger of the State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO), as he deflects criticism from the G7.

Ambassadors of the G7 countries in Bern sent a letter to the Swiss government last April questioning the slow pace at which Switzerland was freezing Russian assets, and claiming loopholes allowed certain individuals to evade the sanctions.

Bollinger leads the Bilateral Economic Relations division at SECO, the organ responsible for coordinating measures under the European Union sanctions packages that Switzerland has adopted. He contends that some of the complaints directed at the Alpine nation, such as the case of the oligarch Andrey Melnichenko, are pure myth.

SWI swissinfo.ch: Switzerland is being harshly criticised internationally over its sanctions regime against Russia. The federal government rejects these criticisms, but has also assigned more staff to work on this issue. What will this do for SECO?

Erwin Bollinger: So far we have taken charge of ten sanctions packages, received over 8,000 e-mail enquiries [and] over 10,000 phone calls. And we’ve had discussions on sanctions with the European Union, Britain, the United States as well as parliamentary questions or motions – a huge amount of new work. It turned out that in the past year our resources just weren’t enough. So we got five temporary positions in 2022 and five more now.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine prompted a series of sanctions on Russian individuals, companies and trade by the European Union, the United States and wealthy G7 nations. Switzerland has kept in line with the EU, implementing its tenth package of sanctions in March.

That has not stopped the international community — including NGOs and more recently the G7 — from criticising Switzerland for not doing enough. They particularly point the finger at the limited amount of Russian assets frozen in Switzerland and argue the Alpine nation could do a better job enforcing sanctions.

In this series we look at what steps Switzerland has taken to conform to international standards and where it lags behind. We question the grounds for sanctions and their consequences for commodity traders based in Switzerland. We also analyse Russian assets in the county and understand how some oligarchs are navigating sanctions.

SWI: So, was the criticism justified that Switzerland was doing too little? After all, these new jobs could have been created a year ago.

E.B.: Before the war in Ukraine, we had eight staff implementing 24 sanctions regimes. Now we have over 20 [staff]. About two-thirds of them are working on the sanctions against Russia. It’s not just a matter of legal opinions and investigations. Cases where assets have been frozen mean plenty of work too. Even if a company is owned by a sanctioned individual, the rent and the salaries still have to be paid. All of those payments have to be approved on an exceptional basis by SECO.

SWI: Your agency has a staff of 800, and the entire federal civil service employs 40,000 people. Having just 14 people working on Russia sanctions doesn’t sound like it’s a top priority.

E.B.: Let’s be careful – we’re not comparing apples and oranges. SECO has other important responsibilities for which other countries have their own ministries. And the number of people is not the most important thing. Quality also counts. The people [we hire] need to be compliance specialists. Other countries like Britain say they are having trouble finding the right people.

SWI: Then you’re agreeing with the critics – that the task hasn’t had enough resources assigned to it.

E.B.: We see it differently. The resources were increased threefold, as in other countries. The European Commission has about 25 people working on the sanctions. And we are not the only ones involved in implementing the sanctions in this country. We have support from other agencies: the State Secretariat for International Finance, the foreign affairs ministry, the Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA), the Attorney-General’s Office, the State Secretariat for Migration, and others.

SWI: On the one hand you lack the people; on the other hand, you have to get help from other agencies. Wouldn’t something like a taskforce beyond the existing structures be more effective?

E.B.: The question is, would a taskforce improve efficiency? We think not. It would only be a change of label. The same people would be doing the work.

More

Switzerland has to ‘go above and beyond’ to implement sanctions

SWI: The new sanctions affect Switzerland on two levels: first, there are enormous amounts of Russian assets parked here, and second, a large portion of Russian raw materials are traded in this country. Which is the bigger problem?

E.B.: We have to implement sanctions in both areas. There is a lot of speculation about Russian wealth here in Switzerland. It’s important to make a distinction between non-sanctioned and frozen assets. We were just about the first in the world to provide figures. The banks are legally required to freeze assets and to then report it to us.

SWI: The Swiss banking sector has undergone important changes as part of the fight against money laundering. Would you say the banks are “clean” now?

E.B.: I would say so, even if I can’t guarantee that there might not still be the odd black sheep. But yes, Swiss banks are being very careful these days.

SWI: Where is money belonging to sanctioned individuals going now? To the US, the Arab world, Hong Kong, China?

E.B.: The banks would know, but we don’t have that information. I must say that the media always focus their reporting on sanctioned individuals and assets. We have plenty of other measures in our 30-page-long regulation – like technology and services bans, and restrictions on the export of goods. These work well, and may in fact be more important in weakening Russia’s military capacity to continue the war in Ukraine.

SWI: What Switzerland is still accused of is aiding and abetting. The whole sector of lawyers and assets managers who weave financial webs is poorly regulated.

E.B.: Asset managers and lawyers have an obligation to report to us in the case of sanctions. There is no obligation to report suspicions of money laundering – although efforts are being made to extend the reporting obligation in such cases to these professional groups. There is also talk of introducing a register of beneficial owners. That would help if it comes, but it still won’t be a magic solution for everything.

SWI: There have been cases in the implementation of the Russia sanctions that earned Switzerland bad press. The commodities magnate Andrey Melnichenko [who has a Swiss residence permit and lives in the ski town of St. Moritz] gave up ownership of his assets in Switzerland before being sanctioned. His wife then became the beneficiary of those assets, which is in a way deceiving Swiss authorities.

E.B.: He was sanctioned by the EU and then Switzerland. But so was his wife – first by the EU and then by us. In the US and Britain, only he is sanctioned, and not his wife.

SWI: In the past year new firms that are suspected of circumventing the sanctions, specifically the price cap on Russian oil, have cropped up in Geneva. Paramount SA and Sunrise Trade SA are among those being mentioned. What does SECO think about these firms?

E.B.: We know about these companies, and have requested information from them. It’s important to understand what the oil cap is – it is not a ban on trading but a price cap. The aim is to maintain global energy supplies without Russia being able to use the profits to fund the war.

More

Investigating Swiss traders’ links to murky world of Russian oil

SWI: Surely this is a system that’s just inviting abuse.

E.B.: The idea came from the G7.

SWI: With the firms mentioned there is some doubt as to whether they are playing by the rules, and they are thought to be owned by Russians. What do you do in a case like that?

E.B.: We have a range of options, including mandatory disclosure and requests for administrative assistance involving the exchange of information with other governments.

SWI: Do companies in the commodities sector have to actively disclose information?

E.B.: They have the same disclosure requirements regarding financial assets that banks do, but no other reporting obligations. In the EU it works the same way. The EU also recommends the documentation of business dealings, which is not legally binding, and which we also support.

SWI: How do you hunt down the black sheep?

E.B.: We rely on information received from partner states or the media. Then there is a complex process.

SWI: You seem to be relying on outside sources of information. That is precisely the criticism that Switzerland and SECO have received – that you only react and you don’t act.

E.B.: That too is a myth. We follow up on tips from a wide range of sources. Other states also work like that. We take a risk-based approach. There’s not much point in following up on every tip or checking out every financial intermediary. Nobody does that.

SWI: The media talk to industry insiders and review public information, like shipping routes. Does SECO not operate this way?

E.B.: We are in touch with companies and have customs statistics and reports made to the Money Laundering Reporting Office. Financial intermediaries are obliged to send these reports, including any violation of sanctions that are a potential predicate offence for money laundering.

SWI: Why doesn’t Switzerland work with an international investigative agency?

E.B.: We exchange facts and figures and documentation on a weekly basis, mainly with the EU, but we also have a good working relationship with the US. Whether Switzerland should be officially part of an international taskforce is more a question of political signaling.

SWI: US sanctions expert Juan Zarate thinks the new norm should be to regard all Russian assets with suspicion. Would that work in the Swiss legal system?

E.B.: That would be a major encroachment on basic rights. It’s hardly conceivable in a country that operates under the rule of law. It will become a point of discussion in relation to the possibility of confiscating frozen assets. I’m not saying it’s completely out of the question for Switzerland, but there would need to be an internationally agreed legal basis, and in individual cases the accused parties would have to be given the right to defend themselves before the courts.

Translated from German by Terence MacNamee/gw.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.