‘We didn’t believe we weren’t being transparent’

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and growing demands from governments and NGOs around the world for more corporate transparency, has put discreet investment groups like Switzerland-based Solway under pressure like never before to open themselves up to public scrutiny.

The modest offices of Solway Investment Group in the town of Zug, in central Switzerland, hardly convey the image of a powerful mining giant. Wedged between a kiosk and a women’s clothing store, the seven-storey building, which hosts some 15 Solway staff on the sixth floor, is typical for Zug – an administrative seat that enjoys the attractive tax rates, discretion, and economic stability Switzerland is known for.

More

Switzerland’s secrecy blind spot hinders sanctions enforcement

It’s easy to stay under the radar here, which suits Denis Gerasev. One of only two board members of the group, Gerasev, who also heads the legal department, has never given a media interview in his 15 years with the company.

Wearing a dark sweater and casual slacks, Gerasev offers a few personal details: the paintings resting against the wall in his office overlooking lake Zug were made by his wife and 7-year-old daughter, who live with him in Oberägeri, a picturesque lakeside town; he used to be a fan of motorbikes but he gave that up when he had kids.

Flanked by a press officer, Gerasev comes prepared for the interview with copious briefing notes, hardly surprising given what he and the company are up against. In November 2022, the US Treasury labelledExternal link Solway a Russian enterprise and sanctioned two employees and two subsidiaries under the Magnitsky Act amid allegations of corruption and Russian influence peddling in the Guatemalan mining sector.

The US Treasury didn’t explain why it called Solway a Russian enterprise and didn’t respond to SWI requests for more information.

Few traces

Solway, which was founded two decades ago, faces an uphill battle trying to defend itself against the US Treasury’s allegations, in part because of its tradition of secrecy despite having a global presence spanning from Indonesia to Ukraine and Guatemala.

Last November, the US Treasury Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) sanctioned two Solway employees and two subsidiaries in Guatemala under the Magnitsky Act, which targets foreign nationals responsible for human rights abuses and corruption. The US Treasury accused the employees – a Russian national and a Belarusian national – of leading multiple bribery schemes over several years involving politicians, judges, and government officials.

In its press releaseExternal link, OFAC called Solway Investment Group “a Russian enterprise that has exploited Guatemalan mines since 2011” and alleged that one employee “conducted corrupt acts in furtherance of Russian influence peddling schemes by unlawfully giving cash payments to public officials in exchange for support for Russian mining interests”.

This came around eight months after a major media investigation involving 65 journalists, drawing on a massive data leak, alleged that the company’s Guatemalan subsidiaries tried to silence indigenous community leaders who spoke out about suspected environmental damage caused by the mining projects. The investigation raised other red flags regarding suspicious financial transactionsExternal link between companies linked to Solway and its executives. The company refuted the allegations, saying they were without factual basis, and opened an investigation into the allegations.

There are bits and pieces on the company website, Wikipedia, and in business registries in Cyprus, Malta and Switzerland, but there’s no clear story of the company’s origins and who is ultimately in control. It caught the eye of US authorities after a series of media reports including a massive investigation published in outlets such as Swiss public television RTSExternal link in March 2022. This alleged the company’s Guatemalan subsidiaries concealed reports of pollution and tried to coerce local community leaders into silence.

More

Swiss mining group suspends Guatemala activities

Solway’s involvement in highly sought-after minerals and metals such as nickel used in electric car batteries, makes it increasingly difficult to remain in the shadows. A recent Newsweek investigationExternal link suggested that the US government is trying to capitalise on the Treasury sanctions to secure access to Solway’s mining assets in Guatemala amid intense competition with China over strategic resources.

“We were never trying to hide anything,” Gerasev said, refuting claims that the company is secretive, despite the lack of information on its website and its reticence to engage with the media. The website makes no mention of Gerasev and has no timeline of the company’s history. It indicates the company has 5,000 employees but there are no photos of executives or managers.

As a private company, Solway is under no obligation to provide any details. There are no shareholders demanding transparency, and no authorities forcing it to publish how board members are selected or compensated.

“Solway is a family-owned company and always has been,” Gerasev told SWI. “It was founded in 2002 by Aleksander Bronstein, who is an Estonian businessman. The aim of the company was to invest in metals and mining across the globe.”

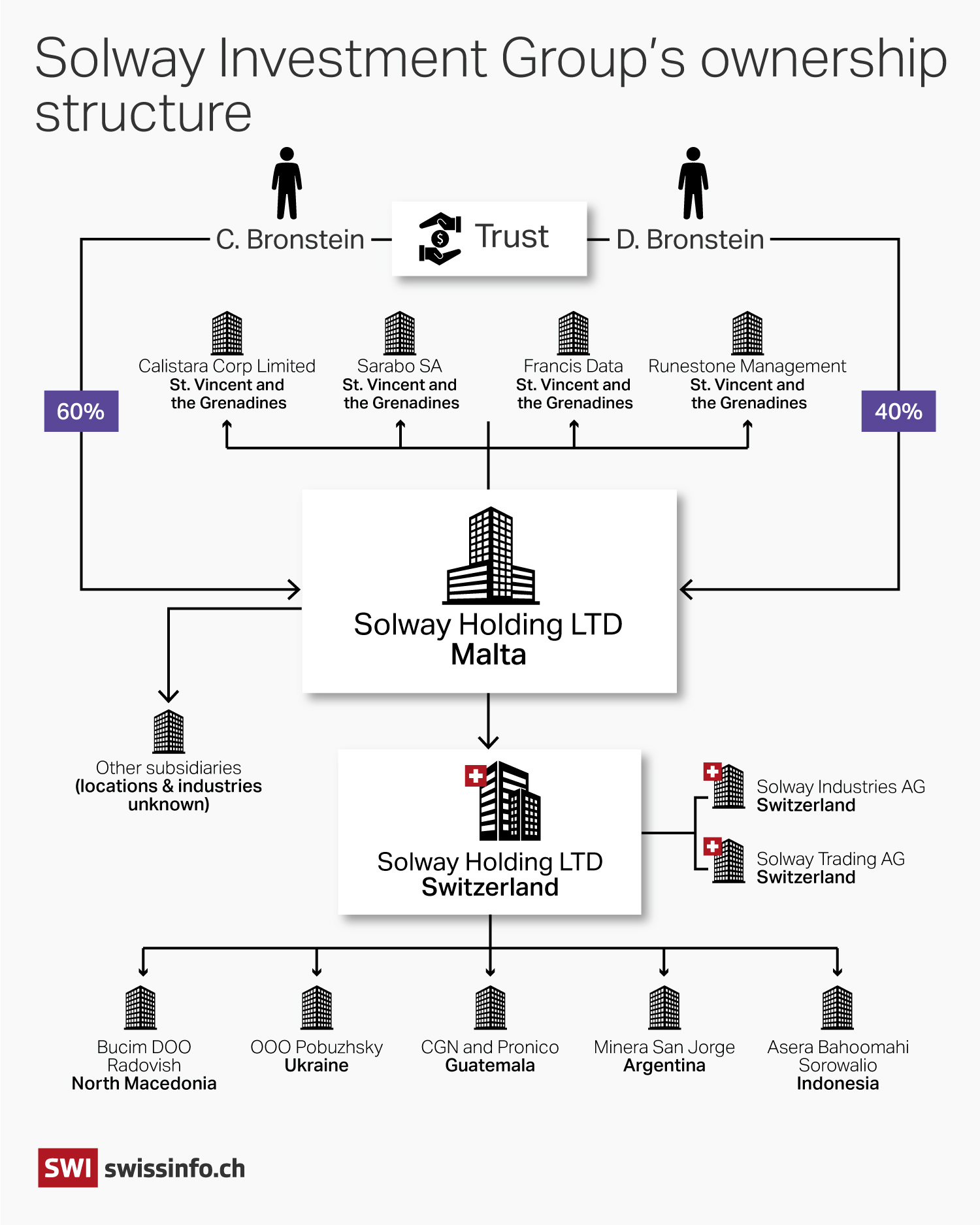

Like many businesses in Switzerland, Solway has used a complex corporate structure that makes it difficult to verify its origins or beneficial owners – those who ultimately have the rights to the company’s income or assets, or the ability to control its activities. The company was originally set up in Cyprus, which is known for offering foreign investors a high degree of anonymity.

Solway moved to Switzerland in 2015, Gerasev said, because it’s a well-known hub for the mining and commodity industry. The attractive tax rate and stable legislation were also factors.

The media investigation found hundreds of transactions between 23 companies with links to Solway or its executives between 2007 and 2015. Gerasev didn’t confirm the number of companies but said that “there’s nothing unusual about that. Companies often use what is called special purpose vehicles for various investments. It’s normal practice for there to be more than one company in a group.”

The Zug cantonal registry lists Gerasev’s name along with Aleksander’s son Dan Bronstein who, Gerasev said, is the company’s CEO. There are three other Solway entities in the Zug registry – two of which the company said are subsidiaries.

More

Data leak implicates Swiss mining company in pollution coverup

Gerasev confirms that the main shareholder of Solway Investment Group is Solway Holding Malta, information also available on the company’s website and in the Zug cantonal registry. The Malta business registry includes three directors and four shareholders, which are companies registered at a single address in St. Vincent and the Grenadines.

“The inclusion of these entities in the corporate scheme was merely to harmonise the corporate governance,” a Solway press officer told SWI in a follow-up email. “These entities will soon be excluded from the ownership structure as a result of the effort to simplify the corporate structure.” The press officer later confirmed that there are 43 direct and indirect subsidiaries of the Malta-registered holding company.

The ultimate owners – who Gerasev said are the sons of Aleksander Bronstein, both German citizens – are not mentioned anywhere on the Malta business registry, nor in the St. Vincent and Grenadines registry. The Malta registry office rejected SWI’s request for documentation, on the grounds that the register of “beneficial owners is limited to competent authorities and subject persons as defined in the Prevention of Money Laundering and Funding of Terrorism Regulations”.

A little over a week before publication of this article, Solway’s legal team shared an extract from the Malta registry with SWI, showing that the sons, Christian and Dan Bronstein, are the beneficial owners with 60% and 40% of the shares, respectively. The company didn’t grant SWI permission to publish the document in light of a EU court ruling restricting public access. A company press officer said that they consider “publication of a document with the personal data of shareholders potentially unsafe, both personally for business owners and their families and for the business itself.”

Russian ties that bind

Questions about Solway’s ties to Russia go beyond ownership. Gerasev is a Russian national who gained Israeli citizenship in 2014. Before moving to Switzerland in 2015, Gerasev lived in Moscow but “grew up in several countries including the Soviet Union, the US and France”.

An archive of the company’s website on the internet shows that Solway, which was previously called the Solway Investment Fund, had a representative office in Moscow and expressed pride in its expertise on the Russian economy. Aleksander Bronstein was a citizen of the Soviet Union before becoming Estonian but never had a Russian passport. From 2003 – 2007 he was a board memberExternal link of the Siberian-Urals Aluminum Company, which was founded by Russian oligarch Viktor Vekselberg, and eventually merged with two other aluminum assets.

Many Solway employees are Russian, but even more come from Ukraine according to Gerasev. Russian is also the “de facto lingua franca of the company” because many people working for the company came from former Soviet republics.

“Having some Russian managers and some people speaking Russian doesn’t mean that the company is Russian, and it doesn’t mean that the company is linked somehow to oligarchs, the Kremlin, or the regime. That’s not the same,” Gerasev said.

He insists that the company isn’t affiliated with the Russian state. This impression, he says, was created by the media in 2014 and has stuck.

“We have a very important subsidiary in Ukraine called Pobuzhsky,” said Gerasev, referring to a ferronickel producer. “When Crimea was annexed by Russia, there was an attempt by some businessmen to take over control of our Ukrainian asset and that was done with a defamation campaign calling Solway a Russian company because since 2014, Russian businesses were not welcome in Ukraine.” SWI was able to find some media reports of an attack on the Ukraine site.

Solway exitedExternal link all its projects in Russia, namely the gold mining operations Kurilgeo and ZGRK, in March 2022, shortly after the invasion of Ukraine, because they were “incompatible with the strategy of the group,” said Gerasev. Solway has also spoken out publicly against the war in Ukraine, and was forced to shut downExternal link its Ukrainian asset after a Russian missile attack destroyed a nearby power station.

Six days after the interview with SWI, the company issued a press releaseExternal link with the first results of a previously announced “independent investigation” into the US sanctions allegations, stating that “although there are connections between Solway, its founder, and Russian business entities and individuals, there is no evidence that Solway, its founder, or its shareholders were historically, or are currently, controlled or influenced by Russian entities and/or individuals in any way.”

Learning lessons

The combination of sanctions against Solway subsidiaries, the Ukraine war, and multiple media investigations are weighing on the company.

“We are operating in a crisis mode,” said Gerasev. “It’s very important for us to get the subsidiaries taken off the sanctions list as soon as possible.”

In addition to the financial impact of having production halted in both Guatemala and Ukraine, the company is also facing more scrutiny from customersExternal link and partners. Last July, Solway and the Salzburg Festival ended a sponsorship partnershipExternal link after the company wasn’t able to fully dispel accusations of human rights abuses in Guatemala. It continues to insist that the accusations were based on false or inaccurate information.

The company is slowly improving its disclosure, albeit selectively. Since March 2022, it has put out several press releasesExternal link on its ESG (environmental, social and governance) commitments including a human rights policy. Gerasev also said there are plans to update its corporate governance structure to include a larger board.

The world is changing as are expectations on our industry, Gerasev said. “We didn’t think we weren’t being transparent, but, yes, we will improve.”

Edited by Nerys Avery/vm

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.