1914: how war changed Swiss life

The first cars rattled over dusty roads, crackling telephones connected people, trams weaved through booming cities – at the start of 1914, Switzerland was dynamic and on the up. But being surrounded by war brought fear and uncertainty to the landlocked, neutral country.

Sources

This article is based on information found in: Un monde bascule: la Suisse de 1910 à 1919 (Anne-Françoise Praz, Editions Eiselé, 1991); Statistisches Jahrbuch der Schweiz 1915, published by the finance ministry; Federal Statistical Office; www.switzerland1914-1918.net; www.license-plates.ch.

One hundred years ago, Switzerland was among the most highly industrialised countries in Europe in terms of per capita production. With 1% of the continent’s population – 3,828,431 inhabitants (less than half the current figure) – it was responsible for 3% of the continent’s exports.

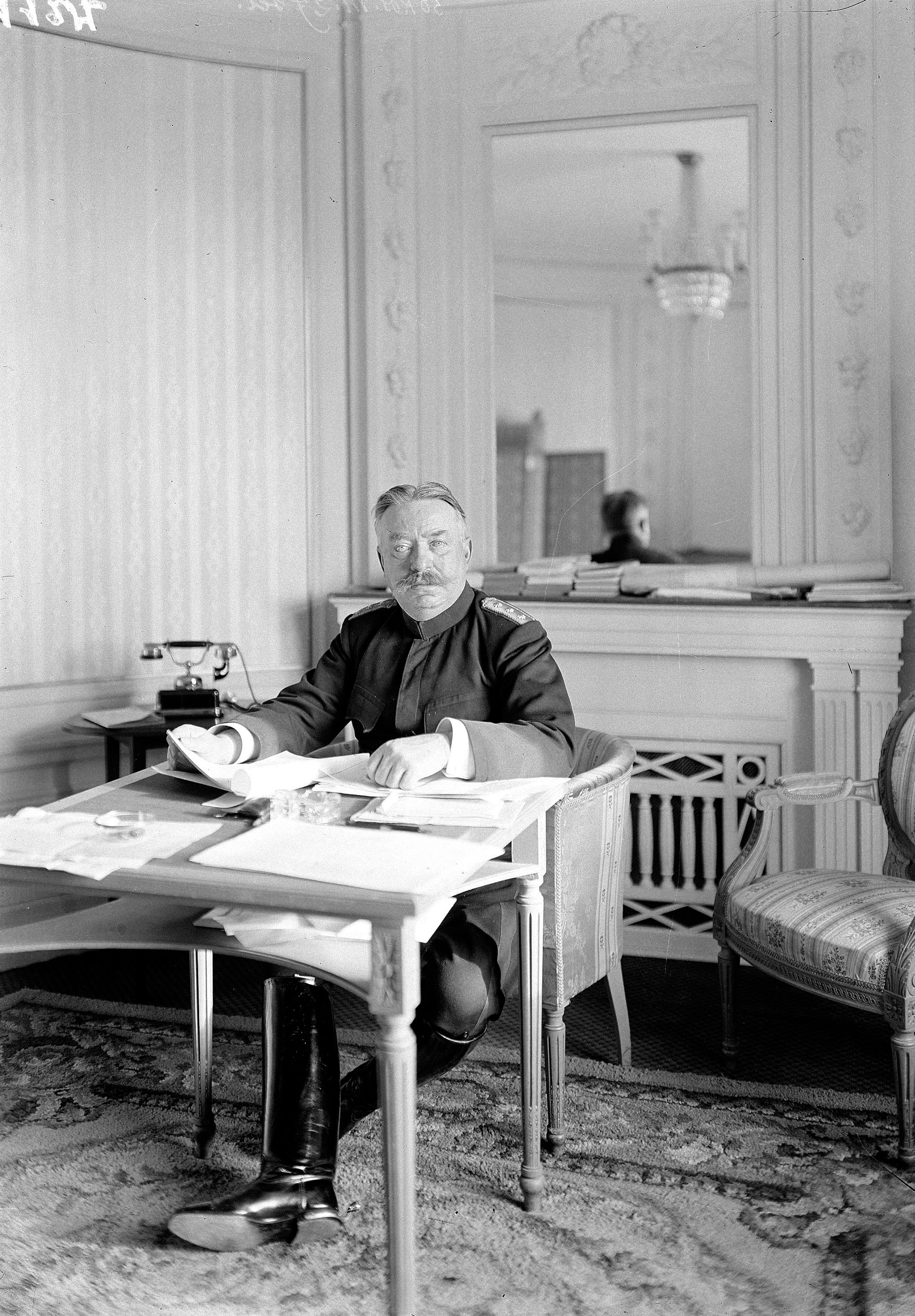

Mobilisation of the Swiss army began on August 2 with Swiss neutrality declared a day later. All Swiss men of military age (20-48) were conscripted. These events in Switzerland coincided with Germany’s declaration of war on Russia and France in the first three days of August.

Newspapers from the French-speaking part of the country – which were generally pro-Allied Powers, unlike their German-speaking counterparts – deplored the “massacre which was brewing”, but they also rallied round the need to defend the country, with patriotic accents of varying intensity.

The socialist press followed suit, but also denounced the “wonderful diversion” which forced European workers to kill one another instead of marching “to attack capitalism”.

On September 19, the Bulletin Démographique Suisse recorded an increase in the number of marriages in the last weeks before the start of the war.

More

Workers fail to profit from golden era

Women’s duty

As part of the war mobilisation, on August 2 the Alliance of Swiss Women’s Organisations launched an appeal to their members. “Don’t make it even more difficult for the men to accomplish a difficult task by complaining about measures which are vital for the defence of the country,” it said.

“Be careful with money so that national food and fuel resources aren’t exhausted too quickly. Take charge in all areas, especially working in the fields and jobs that men can’t do. … We’re asking women with time and energy to put themselves at the country’s disposal to carry out jobs for which they are qualified, in particular in government offices.”

While the suffragette movement was in full swing in Britain – Emily Davison had died a year earlier after stepping in front of King George V’s horse at the Epsom Derby – Swiss women were still 57 years from getting the vote.

On August 21, the Swiss Farmers’ Association urged housewives to come to the aid of Swiss agriculture “which has to save the Swiss population from hunger”.

It encouraged them to buy Swiss veal and pork, which farmers were struggling to sell given the lack of tourists. However, butchers and boarding houses disputed this, pointing out that veal was the most expensive type of meat.

Food concerns

Second only to the fear of invasion was the fear of starvation. The Swiss economy was based on importing raw materials and exporting manufactured goods. It depended to a large extent on other countries for food and raw materials – with German coal making up a sizeable chunk of its energy supply.

What’s more, three-quarters of its cereal was brought in from overseas and Switzerland had no direct access to the sea. Its main communications route, the Rhine, was controlled by Germany.

In the first month of the war, the Swiss had cereal reserves sufficient for two months; there were no plans for long-term provision. People started panic buying and cantonal authorities introduced strict measures: stock-piling was banned, with serious cases being punishable.

Verboten!

On August 15, driving cars was banned – with exceptions made for doctors, military suppliers, food sellers, public utility associations and farm vehicles.

Not that many people had cars: in 1914, of the 5,410 cars in Switzerland, a quarter were in Zurich and a quarter in Geneva.

“Drive as fast as a trotting horse,” was the legally prescribed speed limit (about 18km/h). Police would use a stop-watch to time drivers over a distance of 300 metres.

In November, petrol started to run low. Normally imported from the US or Austria and distributed by a German company, it was now being withheld by both suppliers. At the end of November an American order reached Switzerland via the Italian port of Genoa. The confiscation of oil as part of the war mobilisation was lifted in December, but there wasn’t much traffic on the streets – partly due to a lack of tyres.

1914 Switzerland in numbers

In 1914, Switzerland had 53% fewer inhabitants than it does now (3,828,431 versus 8,058,100 at the start of 2013). In comparison, Spain was 57% smaller, Britain 45% smaller and France and Italy had about 36% and 38% fewer people. Germany was only 17% smaller.

Foreigners accounted for about 12% of the population (today, that figure is 23.3%, although one in five of those was born in Switzerland).

5,677 people acquired Swiss citizenship. This continued to increase, peaking at 12,752 in 1917. In 2012, the figure was 33,500.

Going the other way, 3,869 people emigrated, with 2,890 going to the US and 367 to Argentina. Unsurprisingly, as the war raged around them, more people decided to stay put in Switzerland – in 1915 there were only 1,976 emigrants.

The average number of children per woman was: 2.93, almost halving to 1.53 by 2012.

Natural population change was 8.6 per 1,000 (22.4 birth rate, 13.8 death rate). In 2013, this was 2.1 per 1,000 (10.1 birth rate, 8.1 death rate).

Newspapers

Newspapers were also feeling the heat. The Geneva satirical magazine Guguss was banned in October for the duration of the war. Numerous propaganda publications – on both sides – started flooding the country.

The journal “A propos de la Guerre” was sold in Switzerland “in support of the Red Cross”. Many newspapers in the French-speaking part of the country complained that it was in fact printed in Germany and had pro-Central Powers content.

On November 16, the Basler Nachrichten objected to the distribution of a cheap glossy German weekly written in the three Swiss national languages, giving the impression that it was a Swiss magazine. In fact, it covered the war from a German point of view “aiming to influence Swiss opinion”.

Two days later, the foreign ministry banned the sale of brochures and pamphlets “with a prophetic angle”. Newspapers were also encouraged to not publish this type of article.

On November 16, the cantonal education ministry in Vaud urged teachers to boost national morale and “to refrain from discussing – and to ban pupils from discussing – anything that could harm either Swiss citizens or citizens of warring countries”.

More bizarrely, on October 8, all public dancing was banned in Appenzell and St Gallen for the duration of the war. A ban was also imposed in Zurich but lifted in December.

Watchmen

In October, the watch industry reported a drop in orders, with one British seller refusing to deal with a Neuchâtel company unless it could prove that it had no German staff or funds.

In La Chaux-de-Fonds, the centre of Swiss watch-making, unemployment forced the authorities to come to the rescue of thousands of people.

Chocolate orders, on the other hand, continued to flow in from Britain, Germany and France, although Swiss manufacturers were concerned about supplies of raw cacao and sugar.

Bern’s Toblerone had come on the market in 1908 and in August 1914 took out an advert in newspapers reassuring customers it was business as usual.

Germanophobia

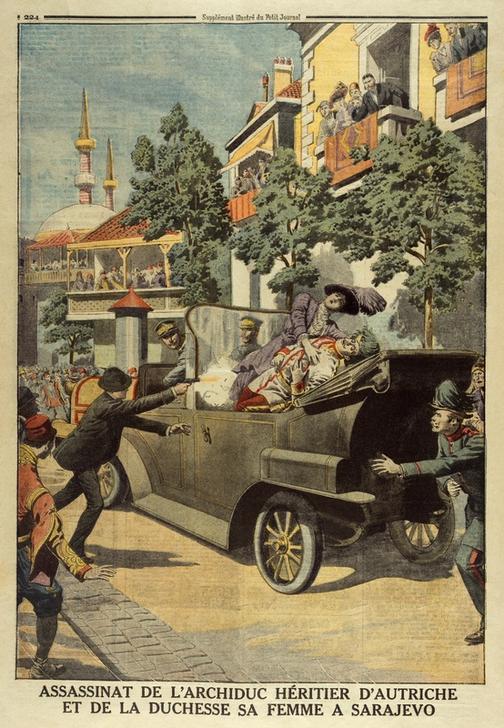

Following the German invasion of Belgium on August 4, many Belgians fled across France trying to reach the border of French-speaking Switzerland.

Swiss who were prepared to take in a Belgian refugee were asked to register with a private organisation run by a woman from Lausanne. Hundreds of responses were recorded within a few weeks.

This hospitality was frowned on by certain newspapers in the German-speaking part of the country. The Berner Tagblatt advised the Belgians to go home, where “under sensible German administration, they could work on getting the situation back to normal”.

In French- and Italian-speaking Switzerland, the press was outraged that there was no official government protest at the violation of Belgian neutrality by Germany. French-language papers – notably La Suisse, La Gazette de Lausanne and Le Pays – denounced the massacres committed by the German army and the bombardment of cities. Some comments were even Germanophobic, with frequent talk of “Boche” and “Hun”.

More

War widens cultural divide in Switzerland

‘Soldier’s Christmas’

Humans were not the only victims of the war. On December 24, Geneva hosted the first international conference for the protection of animals at war. It proposed the setting up of an animal version of the Red Cross, with its own emblem and uniform.

While German, French and British soldiers famously put aside their differences to have a kick-around in no man’s land on Christmas Eve 1914, many Swiss men, despite spending the end of the year doing military service, “were not deprived of festive pleasures”, according to La Patrie Suisse.

Christmas trees illuminated their quarters and goodie packages headed en masse to the borders. A group of women from French-speaking Switzerland launched the “Soldier’s Christmas” campaign, sending packages to Swiss troops at the border. Each package – a red box with a white cross – contained chocolate, biscuits, cigars and cigarettes, some “soldier’s tobacco” and a box of matches.

To keep up morale, the boxes also contained two patriotic songs by Swiss composer Émile Jaques-Dalcroze and a bronze medal engraved with an image of William Tell and the inscription “Christmas under arms, 1914”.

What did people do all day?

According to the 1910 census, 6.5% of Swiss were either in “unidentifiable employment or unemployed”. Of those with jobs, 30% worked in the “extraction of raw materials”, from mining to agriculture and forestry. A larger group (45%) would then “refine” these raw materials, creating for example food, textiles, tools, chemicals and building materials. A further 10% were engaged in business (banking, insurance, trade, hotels and restaurants), 7% in transport (infrastructure and means of transport) and 6% in public administration, academia and art.

Non-war events in 1914

January: Figures for the Swiss watch industry come out for 1913: exports passed CHF180 million but watchmakers are worried about the growing Japanese industry.

March 16: Death of politician Albert Gobat, who jointly received the Nobel Peace Prize with fellow Swiss Élie Ducommun in 1902 for their leadership of the Permanent International Peace Bureau.

William Tell hits the cinemas! Cameramen from Deutsche Mutoskop und Biograph, Germany’s largest film-makers, had arrived in Altdorf, canton Uri, in 1913 with orders to capture the authentic spirit and colour of Schiller’s play. But they were disappointed to discover factories, hotels, trains and telegraph poles. They ended up shooting in less-spoilt nearby Silenen. The owners of the Grütli meadow, considered the birth place of Switzerland, had refused permission to film, citing “patriotic feeling and respect for our past”. The apple scene apparently took days of preparation, and the finished film came in at 2.5 hours with a budget of 100,000 Marks.

June 18: Swiss cyclist Oscar Egg sets a new world hour record in Paris, covering 44.246km. This stood until 1933 (the current record is 56.375km set by Chris Boardman in 1996).

July: In a report on the increasing number of foreigners in Switzerland, the cabinet backs the forced naturalisation of foreigners born in Switzerland whose parents have lived in Switzerland for at least ten years, or whose mother is Swiss or when one of their parents was born in Switzerland.

July 12: To avoid being hit by a double taxation, engineering firm Sulzer moved headquarters from Winterthur, canton Zurich, to the neighbouring canton of Schaffhausen. This didn’t go down well in Zurich and the local press called for a change in the tax law to prevent further departures.

August 1: Swiss National Park is opened.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.