AI regulation: is the Swiss negotiator a US stooge?

Watered down and US-friendly: the Council of Europe’s Convention on Artificial Intelligence has little to do with European values. NGOs partly blame Thomas Schneider, the Swiss chief negotiator, for this.

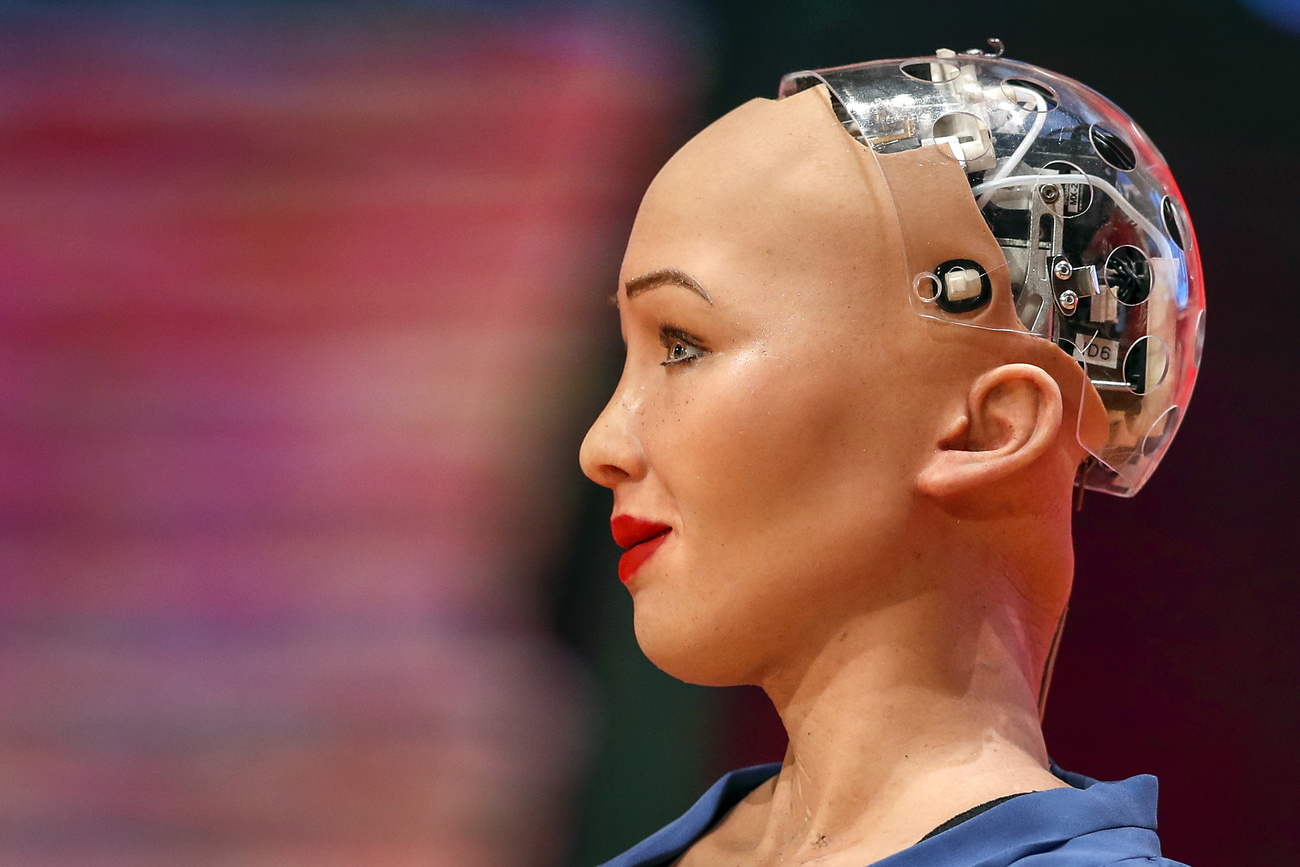

When it comes to digitalisation, politics lags behind reality. This is most evident when drafting a legal framework for artificial intelligence (AI), which has become omnipresent in our everyday professional and personal lives, sometimes without us knowing about it.

Hence various international institutions are trying to find answers to fundamental questions, such as: should human resources personnel use AI to filter applications more easily? How can text or image generators such as ChatGPT or Dall-E be used in schools or law firms? Should there be a blanket ban for real-time facial recognition, or should the police be allowed to make exceptions?

In December 2023 the European Union took the first step when a deal on the regulation of artificial intelligence was reached in what is known as the AI ActExternal link, while the Strasbourg-based Council of Europe is currently trying to draft a legal framework for AI regulations. The Council was founded in 1949 with the purpose of promoting democracy, human rights and rule of law in Europe. It is composed of 46 member states; Switzerland joined in 1963. Delegates in Strasbourg are working around the clock to draft a convention on AI which is due to be ratified in May 2024.

More

The ethics of artificial intelligence

It is surprising that the media have hardly reported on the convention as it will be the first legally binding international rulebook on AI which can also be applied to non-European countries. Governments from all over the world can sign Council of Europe agreements and have them ratified by their national parliaments. This is why the US, Israel, Canada and Japan are sitting at the AI negotiating table. They do not have voting rights, but they do have observer status and the right to have a say.

All these interests make it hard for delegates to find a common denominator, hence a fierce battle over scope and wording is fought behind the scenes. It’s a struggle that could potentially be won by countries that are not part of the Council of Europe and that prioritise the AI industry over human rights – in an agreement entitled “Artificial intelligence, human rights, democracy and the rule of law”, of all things. And with the help of Switzerland, of all countries.

Perfect candidate

Swiss diplomat Thomas Schneider has headed the Council of Europe’s Committee on AI (CAI) since April 2022. The 52-year-old also holds the position of deputy director of the Swiss Federal Office of Communications where he manages the international relationsExternal link unit. He has also worked in various high-ranking positions at the Council of Europe, the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (Icann) and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

Within government ranks, Schneider is considered to have the right skills and a lot of experience; he moves around comfortably on the international stage and listens to the concerns of civil society.

In a nutshell, he was the perfect candidate for the challenging task of leading the negotiations. But now, two years into the job, civil society negotiators in particular are not happy with how things are going, which could also be down to the way the AI committee conducts the negotiations.

Exclusion of civil society

Behind closed doors, government representatives discuss the draft of the AI convention in the so-called drafting group. Delegates of member states such as Moldova, Switzerland and Sweden take part, as well as observer states such as Canada and Japan. Non-state actors such as NGOs, representatives of academia and private companies are excluded from these meetings, but they are allowed to comment on the draft in special plenary meetings and submit proposals for amendments.

Schneider justifies the exclusion of non-governmental actors as follows: “The delegates need an environment they feel comfortable in. This is the only way they can find a compromise and convince their governments that they gave absolutely everything in the negotiations.”

It was different when Convention 108+ for data protection was signed in January 1981. Back then, representatives of civil society and governmentsExternal link had joined the discussions and sat together at the negotiating table. Excluding civil society representatives from the drafting group for the AI convention was already a “red flag”, says Marc Rotenberg of the US Centre for AI and Digital Policy, a non-profit thinktank which has accompanied the negotiations since the beginning. “This was a bad start.”

At the beginning of the negotiations, the AI committee still listened to the concerns of civil society, some participants in the talks observed. But the modus operandi of the negotiations has made it impossible for NGOs to correct the compromises previously agreed upon by governments.

Primarily global convention

Representatives of civil society are not happy with the latest outcome of the talks. Two years ago, human rights were still at the centre of the negotiations, but the latest version seems to be more of a declaration than a binding treaty, writes the news portal EuractivExternal link.

More

ChatGPT: intelligent, stupid or downright dangerous?

Important aspects such as the impact AI systems have on the environment and energy have been left out completely, while the draft allows AI systems for national security to be exempt from the regulation. Several participants agree that this is no longer about equality and non-discrimination – the core values of the Council that are enshrined in the Convention on Human Rights – which is absurd because in its mandate, the Committee on Artificial Intelligence has vowed to adhere to the principles of the Council of Europe.External link

But, as Schneider writes on the Council’s website, this change of heart could also be due to the Council’s desire to go global. “We all agree that we intend to develop an instrument that is not only attractive to states in Europe, but to as many states as possible from all regions of the world.”

Schneider further explains that the Council of Europe commissioned him to take a global approach, which is part of his mandate. “If we consider only what’s good for Europe, other countries will not be inclined to sign the convention. We must take into account other cultures and legal systems.”

But nowhere is it written that the AI convention must be signed by as many countries as possible. The committee’s terms of referenceExternal link state that “a global view of the subject” and an “inclusive consultation process with international and supranational partners” must be ensured. Schneider points out that this is exactly what the negotiating partners want. So far, nobody has contradicted what he wrote on the AI Committee’s website.

US lobbies against strict rules

The main bone of contention is the scope of the convention. According to Schneider, the regulations should be “conducive to innovation”, which calls for countries with the largest AI industries to be on board. “Otherwise, Europe will remain a ‘closed club’.”

However, it is precisely the promotion of innovation and the global scope of it that cause tensions. US delegates have proposed not to adopt binding guidelines for the private sector, which seems to be the delegates’ reaction to pressure from their AI industry.

More

A special relationship: The US military and Swiss universities

In an open letter to the US Secretary of State Antony BlinkenExternal link from January, 24, 2024, US pressure groups issued a warning: “We write to strongly recommend against the inclusion of binding standards for private industry.” This would massively jeopardise the United States’ political and economic leadership in the burgeoning field of AI, they wrote. The alliance says that the EU had already implemented discriminatory tech legislation targeting US companies such as the Digital Market Act.

The governments of Canada, Japan and Britain agree. They argue that such conventions traditionally protect citizens against state interference and not against threats from private individuals.

But critics disagree and call this argument outdated. “When it comes to AI, private companies pose the greatest threat. Hence, such conventions must target the private sector,” says NGO representative Rotenberg. Keeping the private sector out of the scope would also mean that enterprises spreading deepfakes and disinformation could do so without suffering any consequences.

Open letter

In an open letterExternal link, more than 90 NGOs and academics – among them AlgorithmwatchExternal link Switzerland and the Digital Society– have called on the negotiating states to include both private and public sectors in the convention.

Karsten Donnay, assistant professor of political behaviour and digital media at the University of Zurich, put his signature on the letter. “We either include everyone or no one,” he says.

Tarek Naguib of the Swiss NGO Humanrights.ch also welcomes the fact that the convention is not “exclusively European”, but he has some reservations. “If we allow companies to be exempt from the regulations, we will send a signal that human rights can be compromised.” Naguib also signed the appeal.

In the latest development, the drafting group has come up with two options. One is the “opt-out” option which makes the convention binding for both public and private sectors but gives the signatory states the right to temporarily exempt private companies. Under this option, the situation will be reviewed after a few years. Civil societies and the EU advocate for this option.

The other one is the “opt-in” option which makes the convention binding for the public but not for the private sector. However, governments can “seek to ensure” that adequate measures are in place for the private sector. The wording implies that these measures are not legally binding and cannot be enforced by law. The US lobby is heavily in favour of the opt-in option which has caused some outrage among civil society.

This is a nasty game, says an insider. “If the opt-out option were adopted, the US would have to come clean, which would make them the bad boys. This is why they want to lower the standards for all signatory states.”

The Swiss delegation is also in favour of the opt-in option, which makes it an ally of the US in this matter.

Little chance of being ratified in the US

If the delegates decide for the opt-in option in the last round of negotiations, the US and other business-friendly governments will be the winners. And once ratified by the US, Switzerland could say the convention was a great diplomatic success.

This is what Swiss chief negotiator Thomas Schneider is hoping for. However, there are two major hurdles that make it almost impossible for the US to ratify the convention: it needs a two-third majority in the Senate and the president’s signature. US lawmakers widely agree that it is rather unlikely for the US parliament to ever approve this convention.

More

Is artificial intelligence really as intelligent as we think?

Are Schneider’s expectations too high? “I don’t know whether the US will sign the convention or not,” he says. “It would certainly send out a strong signal. And for other countries, it is important that the US was involved in the negotiations.”

Some doubt the Swiss chief negotiator’s neutrality during the negotiations, as reported by the news portal EuractivExternal link. “Sources familiar with the discussions confirmed that the chair and the [Council of Europe’s] secretariat were not neutral throughout the negotiations, instead pushing for the arguments of the US and other observer countries while putting aside contradicting ones.”

Schneider thinks this accusation is unfair: “All sides accuse me of not giving their position enough attention.” He explains that he acted as moderator and service provider and was not allowed to express his opinion. “In cases of doubt, I’d rather include another amending proposal in a document, even if I’m sure that it doesn’t stand a chance of winning a majority.” Schneider believes it is important to talk to and listen to everyone.

But Schneider also enjoys some support. His supporters say that this is how diplomacy works; that he has a tough job, but going global was the right approach. They understand that Council of Europe conventions are generally abstract as they had to be implemented by the individual governments and needed a lot of leeway for the legal systems. “You have to be realistic, and the AI Committee is,” says one participant.

Euractiv came up with the theoryExternal link that Switzerland would benefit from a diplomatic victory as Alain Berset, the former Swiss interior minister, is one of the key candidates for the post of Secretary General of the Council of Europe. But when asked, Berset refused to comment. Schneider does not believe in such rumours either: “Over the past 13 years, I have spoken to Mr Berset two or three times. He probably wouldn’t even recognise me.”

Adapted from German by Billi Bierling/ts

You can read the full report in German hereExternal link.

Do you want to read our weekly top stories? Subscribe here.

More

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.