New director of Bern’s main art space wants to start a conversation

In May, South African curator Kabelo Malatsie arrived in Switzerland to run one of Bern’s main art institutions, the Kunsthalle. SWI swissinfo.ch met her to talk about her concept of curating and what she thinks should change in the art world.

The appointment of South African curator Kabelo Malatsie to succeed Valérie Kroll as head of the Kunsthalle was intriguing. Not only is she the first non-European to head a public Swiss art institution, the former Johannesburg resident also followed an unusual career path.

Malatsie first studied marketing management before moving to art history and ultimately curating. She began her professional life in the arts as acting director of the Stevenson in Cape Town, a commercial gallery, before bringing her expertise to an artists’ rights organisation. She is best known curatorially for her work within the Yokohama Triennial 2020 (Japan). She was asked by the curators of the show, the Raqs Media Collective (Michelle Wong and Lantian Xie), to curate a discrete and complex programme called Deliberations on Discursive Justice.

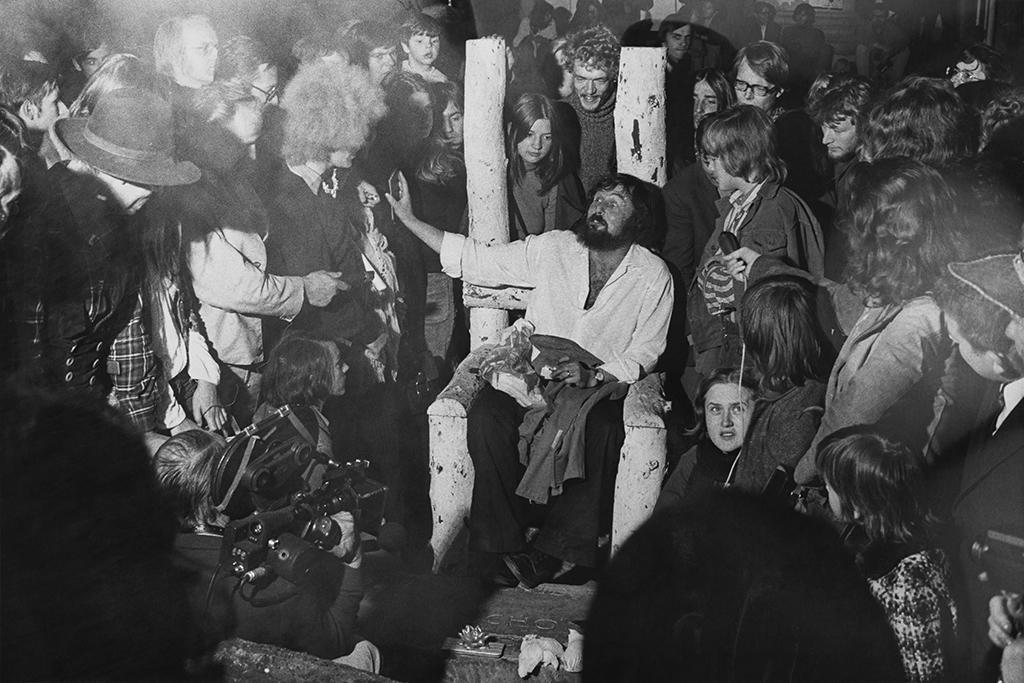

Her appointment as the new head of the Kunsthalle – an art space without a permanent collection – is part of the institution’s long disruptive tradition. In the 1960s, it was the epicentre of radical experiments led by its head Harald Szeemann – which eventually cost him his job. Decades later, in 2015, the Kunsthalle appointed a woman for the first time to head the institution, Valérie Knoll. Malatsie, as a non-European, brings to Bern a new perspective on what curating and art spaces can mean.

SWI swissinfo.ch: You’ve scarcely had time to unpack your bags. How do you intend to explore the city of Bern and its arts scene?

Kabelo Malatsie: I’m letting people who have been working in this space and who live in Bern help me navigate it. I will be walking a lot.

SWI: In the art world, the Kunsthalle Bern is known for experimentation in the contemporary field; nonetheless, Bern is quite conservative. How do you perceive your audience?

K.M.: To be truthful, I haven’t yet met the audience. It would be disingenuous for me to say that I’m going to curate with the audience in mind. My approach is to do shows that I’m interested in and hope that this will generate conversations. This is what I’m interested in: having a platform for ideas and a more dialogic approach to curatorial practice rather than ‘I’ll show you something that is finished and closed’, closing off any potential for feedback and conversation.

The other thing that I’m interested in is working with young people, especially for them to challenge the Kunsthalle. Even though it’s known for experimentation, I’m sure it’s now old and institutional, and [this condition] can stifle critique.

SWI: What was the appeal for you to work in the Kunsthalle?

K.M.: It’s somewhat of an empty container; it has no permanent collection and as a director, it comes down to your own curatorial interest to fill the space. Though we will be working with artists over a relatively short time, it would be great if we can define working models we can test out together, and that artists can take with them in their future work.

SWI: You once remarked that your early conception of curating was putting objects on walls. How has that concept expanded since?

K.M.: At the beginning of my understanding of curatorial practice I was thinking more along museum curating, which can be very conservative. Now I think that even administrative work can be curatorial. One can think about Excel spreadsheets creatively, and go beyond balancing money; we can think of different resources that go into making an exhibition.

When you’re doing a project you start ambitiously, conceptually, then the concept starts sinking when day-to-day issues take over. I’m hoping that, as the administrator, I can encourage a working practice where the conceptual stakes are always high and I am not reducing concepts and getting bogged down by practicalities.

SWI: How would you define an art space?

K.M.: Creativity is everywhere. Space for art is everywhere. I read an interview a long time ago where [Brazilian artist] Paulo Nazareth said that even if he stopped making art objects and was a fisherman, he would still be an artist as a fisherman. The curatorial practice can go into multiple directions.

SWI: I can understand your perspective, but is a gallery, or a museum, still the privileged space for art?

K.M.: There’s the old-fashioned Western way of doing things: things are [categorised] in neat boxes. This is where we have art, this is where we have medicine and so on. (When I mean Western, I mean colonised places as well.) So, in South Africa things are in boxes, too, more so in formal institutions.

For me these boundaries are no longer important, so long as what you’re doing makes sense. A good example is Stephen Alexander, a physicist and a jazz musician; you can be thinking about scientific questions whilst doing an artistic activity. So, I am not really caught up in defining what is curating, or what is art.

SWI: I guess we’ll have to see what happens in the Kunsthalle…

K.M.: There will be art objects, there’ll be performances. There are a set of questions that I’m trying to answer with each exhibition. Each work will be trying, not to answer, but to grapple with a question that I have.

SWI: For many art institutions and galleries Covid-19 meant slowing down and a refocusing on how exhibitions are produced and mediated. Did this affect your thinking?

K.M.: When museum and exhibition spaces were closed, the art world was putting their artworks online, and there was nostalgia for being in a physical exhibition space. And I was thinking back to the conceptual art of the ‘60s and ‘70s and how the idea was more important than the object. The idea of moving from the fixation with the art object, into a space of ideas, hasn’t really evolved since.

If we are closing galleries and exhibition spaces, then the ideas should really be able to live on. There was this dissonance around the art object’s importance and that the object carries ideas beyond the fact that it is an object. Some of the online interventions were trying to recreate the exhibition space. I felt like we were missing an opportunity to push the idea introduced by conceptual artists many years ago.

Whereas the music scene has always been able to adapt to every technological change without losing its essence. Art, on the other hand, seems stuck technologically, it doesn’t move.

SWI: I fear that it is hampered by the market.

K.M.: Yes, but the thing about the market is that it’s such a small group of people.

SWI: But it’s often the way that art gets in the public eye.

K.M.: We need to find a way out, no? Otherwise, we have to accept that things don’t move.

Edited by Eduardo Simantob

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.