Top Swiss economist: ‘We have to pull together’ on pension reform

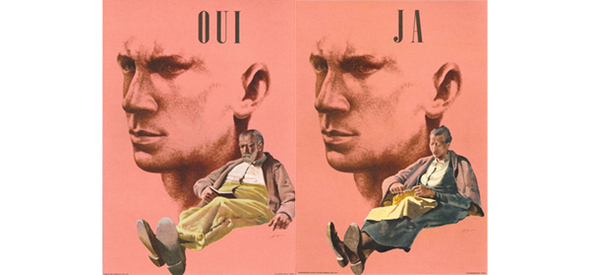

Rudolf Strahm is one of Switzerland’s most reputed economists. Here, he shares his opinion of Pension Reform 2020, which will come to vote on September 24.

swissinfo.ch: The old-age pension system has been revised ten times since its introduction in 1948. The last revision was in 1997. Since then, every attempt at comprehensive reform has failed. Why?

Rudolf Strahm: Swiss voters don’t like to take major steps. Reducing benefits is not an option. This has been rejected three times. Increasing taxes all at once is also not an option. The current proposal takes small steps forward and is well balanced. It’s a proposal with the potential for general acceptance.

swissinfo.ch: You predict that the proposal will have a good chance of passing on September 24?

R.S.: I’d give it a good chance of passing. There’s a moderate level of dissatisfaction in Switzerland at the moment. A rational compromise could find acceptance. Votes on pension reform have always been very emotional. The Swiss remember this. Pension reform has failed many times. Now it appears that there’s a level of fatigue that may make a ‘yes’ vote possible, and recognition that ‘in the end we have to pull together and reach a compromise’.

swissinfo.ch: Can you explain why historically the old-age pension system – which is considered a major achievement of Swiss social policy – has been criticised over so many years?

R.S.: Switzerland has a three-pillar pension system. The state pension, known as the first pillar, is Switzerland’s oldest form of social insurance. For generations, it was perceived as a major step towards keeping the social situation under control. It was put forth for the first time by the Socialists from Neuchâtel in the 1890s and in 1918 it was one of the core demands of the General Strike. In 1947, after a bitter battle, the old-age pension insurance was passed by 80% of all voting men, with 80% voter participation. Part of the private insurance industry and private business owners – led then by the Neue Zürcher Zeitung newspaper – was against state pension insurance. The NZZ described the proposal in 1943 as an “unwholesome descent into egalitarian nationalisation”. The opponents were a small group, but always vehement and spiteful.

swissinfo.ch: You’ve been accused of talking badly about the occupational pension plan, also known as the second pillar. . .

R.S.: The occupational pension plan is an integral part of Switzerland’s three-pillar retirement system and no one – myself included – questions its importance. It involves contributions to a pension fund over the course of a lifetime of work. The occupational pension plan’s funding scheme is more stable over the long term with regard to demographic developments. But with today’s low interest rates – and they can be expected to continue for a number of years in Switzerland – the occupational scheme is actually more expensive. In 2015 it generated CHF 5.8 billion ($6 billion) in interest income, but CHF 3.8 billion of that was eaten away by asset management and CHF 0.9 billion went to cover the costs of administering the pension funds. One in seven francs in the retirement system disappears. Those are figures from the Federal Statistics Office.

swissinfo.ch: What does that mean concretely?

R.S.: In today’s low-interest-rate environment you need to pay more into the occupational pension than into the state pension if you want to generate an overall pension of CHF1,000. That’s also the political background as to why the debate over the first and second pillars has been rekindled.

swissinfo.ch: How would you describe the role of insurance companies and banks?

R.S.: For bankers and wealth managers, the state pension is certainly not their favourite thing. We’re talking about a state-run, pay-as-you-go system. Naturally, private insurance has always wanted to promote individual retirement savings (the third pillar of Switzerland’s three-pillar system), as well as the occupational plan. The political left, on the other hand, has demonised the occupational pension plan. But the three-pillar system became politically and economically anchored in the 1970s and 1980s and so can’t be easily changed. But every time there was a conflict over the distribution between the first, second and third pillars, people evoked crises and end-of-the-world scenarios, only to be proven wrong time and again.

swissinfo.ch: The young generation feels insecure.

R.S.: There will be pensions for young people as well. The system has remained stable over the past 70 years. Adjustments are possible, but there have never been cutbacks. The almost two million pensioners can prevent that through a referendum. If there’s a need for more financing later, this can be done in small steps. The current proposal is cautious as well. And in 2030 we’ll consider the issue again. That’s the Swiss approach.

swissinfo.ch: People are living longer. This development is a reality, and is straining the concept of intergenerational solidarity.

R.S.: That’s true. And this was forecast back in the 1990s. Government projections in 1995 foresaw a deficit in the old-age pension system starting in 2005. But this was repeatedly delayed due to increases in wages: when total wages increase, so does the revenue for the old-age pensions. And then in 1999 – with very little fanfare – a percentage of the value-added tax (a consumption tax on non-essential goods) was earmarked for retirement insurance. That led to a major postponement in losses.

swissinfo.ch: How much longer will this contract between the generations continue?

R.S.: It is still very strongly anchored, despite the fact that it has repeatedly been questioned and is under attack again in the run-up to the current vote, with questionable mathematical models being used to mobilise young voters.

The system won’t collapse after 2030 either.

swissinfo.ch: Should we be concerned?

R.S.: The need for change in the current financing system is undisputed, even from the political left, which didn’t agree on this ten years ago. Today, disagreement over the proposal coming to vote in September is not over whether something has to be done to ensure the system remains stable and pensions can be guaranteed. Now, the issue is which bitter pills will have to be swallowed. And the old ideological question remains: is it better to have a solution from the state or from the semi-private sector?

swissinfo.ch: Let’s focus on the bitter pills. Who will have to swallow the biggest one?

R.S.: Every group has what it considers to be one or more bitter pills. The political left has the biggest: an increase in the retirement age for women from 64 to 65, without compensation through improving women’s salaries. But a proposed CHF70 increase in monthly pension payouts is some compensation for the other losses that will be incurred.

swissinfo.ch: Who will in fact profit from the pension reform proposed by Interior Minister Alain Berset?

R.S.: People aged 45- 64 today are the most likely to profit. This transitional generation would receive a little more pension money if the reform passes, and the planned reductions in the second pillar wouldn’t take place until later. People who are already retired or will retire in 2018 won’t lose anything, but they won’t gain anything either. What the situation will be for people under 40 can’t be predicted. We don’t know what will happen in the next quarter-century in terms of economic growth, immigration, the birth rate, or value-added tax (VAT). I’m assuming that old-age pensions will have to be financed by a further percent increase from VAT after 2030. I’m in favour of an increase in the VAT, rather than increasing the percentage of salary paid into the pension fund. This is because well-to-do pensioners would also have to pay the tax.

swissinfo.ch: Would it still be possible today to create a social insurance programme like the old-age pension system?

R.S.: Not with the current parliament. The welfare state, with its historical development and a quarter of the gross domestic product, is at the limit of political acceptance. It’s not a question of our ability to finance such a programme. We still have lower taxes and a lower GDP ratio than all the countries around us. But politically and psychologically it’s at the limit. Of all the branches of social insurance, though, I would consider retirement funding to be politically the most stable. Social welfare is at greater risk, because we have high immigration into these systems due to migration from poor countries.

swissinfo.ch: What lessons can be learned from Switzerland?

R.S.: We can’t really make condescending recommendations about what should be done abroad, especially since our system has developed historically. In 1948 the old-age pension (first pillar) was introduced, then in 1985 the occupational plan (second pillar) became compulsory, and it wasn’t until the 1980s and 1990s that the status of private retirement savings (third pillar) was improved through tax breaks.

In my opinion, a combination of pay-as-you-go financing for the state pension and a contribution funding scheme for retirement funds is ideal. Both have advantages and disadvantages. The contribution system stabilises demographic development, but in today’s low-interest market the capital can’t be beneficially invested. Meanwhile, the advantage of the state pay-as-you-go method is that a strong economy can finance the pensions. The disadvantage is that it puts more pressure on public coffers. Countries like France, that have a completely government-funded pension system, are going to have big problems as a result of the changing demographics.

swissinfo.ch: Old-age pensions are a means of fighting poverty in old age, but ultimately do they contribute to stability and peace between the social classes?

R.S.: Yes, to both financial stability and social harmony. And they contribute to identification with the Swiss social system as a political system, but also to companies as employers, and to Switzerland as a business location. And this identification – this desire to contribute to the country and its economy – goes beyond social stability. We feel secure here in Switzerland. Our system works!

Translated from German by Jeannie Wurz

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.