Unique skull find could rewrite the history books

Swiss and Georgian researchers have suggested that some of the earliest humans living 1.8 million years ago could all belong to the same species, doing away with other categorisations because they lack enough major differences to set them apart.

The scientists are aware they could be re-writing the history books, killing off whole species from humanity’s family tree. “We felt especially like the kid in the tale about the emperor’s new clothes,” Christoph Zollikofer of Zurich’s Anthropological Institute and Museum told swissinfo.ch.

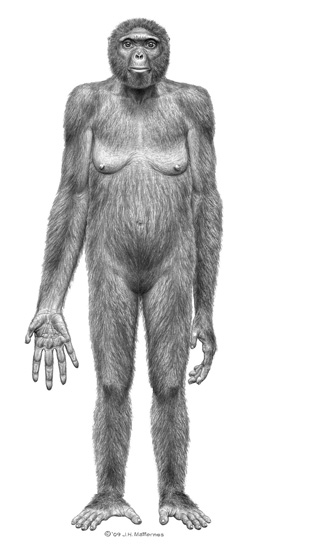

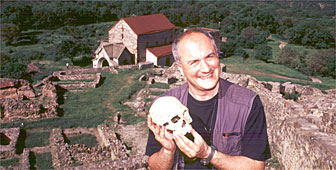

A skull dug up in Dmanisi in the southern part of Georgia is the key to the puzzle according to the scientists. Unearthed in 2005 and matched with a previously discovered jawbone, it is the most complete cranium of an adult Homo erectus found to date.

Skull 5, as it is known, has a small braincase, a long face and large teeth. “The interesting thing is that it didn’t come alone. We had four additional individuals found earlier, which allowed us to look at variation in one location in time and space,” said Zollikofer, one of the lead authors of an article published in the journal Science on Thursday.

The researchers’ working hypothesis was that the fossils belonged to one population, even if they would have looked very different from one another.

”What we found was […] they didn’t look any different than five humans you would pick out of any population,” added Zollikofer. “Having shown that, we are convinced that the five individuals represent variations within one species, early Homo.”

The Dmanisi excavation site is two hours drive south-west of the Georgian capital, Tbilisi, beneath the ruins of the medieval town of Dmanisi. It provides a record of the earliest hominid dispersal beyond Africa.

The first mention of the town itself dates back to the ninth century, although it is believed to have been settled at some time in the Early Bronze Age.

During the Middle Ages, it was a major local commercial hub.

The first archaeological work was carried out in the 1930s, when Georgia was part of the Soviet Union. Primitive stone tools were however uncovered only in 1984, sparking further interest in the site. After 1991, international researchers joined their Georgian colleagues in Dmanisi.

Human fossils were discovered at the site between 1991 and 2005, and some have been dated back to 1.8 million years. They represent the oldest proof of human presence in the Caucasus.

According to David Lordkipanidze of the Georgian national museum, the state of preservation of the fossils found at the site is exceptional, allowing for the study of previously unknown aspects of the skeleton of fossil hominins.

Due to the volcanic origin of the Dmanisi sediments, the site is dated to 1.77 million years before present.

One species

Usually, paleoanthropologists have used the variations among Homo fossils to define different species. But the latest research from Zollikofer and his colleagues suggests Homo remains from that period from other sites are part of the Homo erectus family.

“We referred to contemporaneous finds from Africa, where there are a wide diversity of fossils from around 1.8 million years ago,” he told swissinfo.ch. “The amount of variation and differences we saw were no different to what we would consider normal variation within a species.”

The results were produced using so-called 3D geometric morphometrics, with Zollikofer and his colleagues analysing the data afterwards to quantify variation. Their conclusion is that for example Homo habilis, Homo rudolfensis, and Homo erectus, categorised in three different species until now, could actually be all the same one.

According to Zollikofer, the whole hypothesis could not have been established if Skull 5 had been found as a separate braincase and jawbone in different locations, which would have probably led researchers to consider them as belonging to different species. The complete skull has key features not observed together until now, such as its small space for the brain and large jawbone.

“We said to ourselves there was probably not much out there, just one species,” he added.

“This does not mean we think there is one species along the whole line of human evolution, because we are only looking at a specific point in time, 1.8 million years ago.”

Evolving picture

The Zurich professor says he feels no apprehension at bringing about change, adding the data speaks for itself. He is under no illusion the results will be challenged though.

“This is what you live with in science,” he admits. “This can happen to us too, probably in several years if there are new finds. We shouldn’t tie our scientific standing too much to specific hypotheses.”

Chances are something will turn up that will alter scientists’ perceptions. According to David Lordkipanidze of Georgia’s national museum, there are still another 50,000 square metres of ground containing fossils and stone tools to excavate in Dmanisi, the equivalent of seven football pitches.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.