Study shows it doesn’t take brains to emigrate

A new fossil find suggests that it may not have taken either brains or brawn for early humans to move out of Africa.

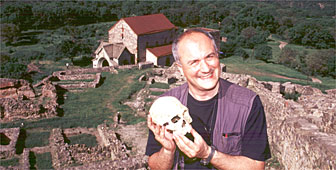

A team of Swiss and international researchers has discovered the skull of a small, lightly built individual at an archaeological site in Dmanisi, Georgia.

The size of the skull raises the possibility that the large brains which characterise modern humans did not necessarily evolve before our ancestors began migrating all over the world.

The study is reported in Friday’s issue of the journal Science. Among the researchers are two experts in computer-assisted skull reconstruction from Zurich University.

The skull was discovered in volcanic ash beneath the ruins of a medieval settlement about 80 kilometres from the capital, Tbilisi, near the border with Armenia.

Like two other skulls discovered at the site, this new specimen dates back about 1.75 million years. However, its braincase is substantially smaller.

Most primitive hominid

“The importance of this find it is the earliest human presence out of Africa and it is also the most primitive hominid skull ever found in Eurasia,” project leader, David Lordkipanidze, deputy director of the Georgian state museum in Tbilisi, told swissinfo.

The individual’s brain size was about 600 cubic centimetres – half that of modern brains and well below the range attributed to Homo Erectus and even to Homo Ergaster, forms found in East Africa.

“This very small-brained individual bears striking similarities to the fossils from East Africa that are called Homo Habilis which, by our reckoning, is the first species known to our genus Homo.” said Reid Ferring, professor of geography at the University of North Texas in Denton, Texas.

“We need to establish the context of these people and try to find out more about how they got there, why they got there and what role the environment played either as a barrier to immigration or as an enticement to immigration to this region about 1.8 million years ago.

“If we get three kinds of humans at the same time in Africa and three kinds of humans at the same time in Eurasia, it suggests a pattern that we have not been aware of before.”

Sophisticated technology

Many scientists believe that fully-fledged Homo Erectus was the first species to leave Africa for Eurasia and boasted a fairly sophisticated technology including hand-axes.

The Dmanisi finds suggest that early humans moved out of Africa hundreds of thousands of years earlier than previously thought while the simple flake tools discovered at the site question the assumption that sophisticated stone tool technology was required for migration.

Reasons for the move also need revising. According to the traditional scenario, increased intelligence enabled these early humans to adapt to new environments.

“The problem with all these adaptive explanations is that you see a pattern and you try and interpret it with hindsight,” Christoph Zollikofer, a specialist in computer-assisted paleoanthropology at Zurich University, told swissinfo.

Big brains

“In my view why humans evolved big brains and why these brains got even bigger in the past 100,000 years is a complete conundrum.”

Zollikofer and his colleague and Marcia Ponce de Leon use modern technology to study fossils. They have developed computer software, which can reconstruct on a computer screen the missing parts of early humans and study the inner structure of the bones.

Computer graphics also allow them to compare the Dmanisi individuals with fossils from other parts of the world.

“It’s the most complete human skull and mandible that has ever been found from that time so we see details of anatomy which nobody has ever seen before,” said Zollikofer.

“We hope to find even more of this specific individual and other individuals at the site because these fossils are extraordinarily well-preserved. I think it will turn into the Pompeii of paleoanthropology.”

by Vincent Landon

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.