The South goes North: documenta15 turns the art world upside down

A heated controversy over antisemitism overshadowed important issues raised by the ambitious contemporary art show that takes place every five years in Kassel, Germany. But the exhibition, that ended on September 25, will go down in history as a milestone in the North–South artistic divide.

documenta fifteenExternal link faced higher expectations than usual. It was the first time that a group – the Indonesian collective of artists and activists ruangrupaExternal link – was appointed to its artistic direction, instead of a “super curator”. But more significantly, it was also the first time that documenta was placed in non-Western hands.

Their appointment was politely welcomed as it ticked many politically correct boxes. However, the debate on antisemitic depictions (see box below) practically monopolised the local and international coverage of the show.

“It makes me very sad,” Indra Ameng, one of the members of ruangrupa, told SWI swissinfo.ch. “This whole discussion sidelined more promising discussions we wanted to raise, and we were thrown into a debate that wasn’t ours”.

Ameng doesn’t mean that antisemitism is irrelevant for ruangrupa, but that it is an imported question. As the Swiss historians Bernhard Schär and Monique Ligtenberg explained in an articleExternal link about the long-lasting effects of colonialism and the Suharto dictatorship, “anti-Semitism in Indonesia is not a Javanese invention. It is the complex legacy of a colonial, including German, cultural export that contemporary Indonesians have appropriated and transformed.”

documenta fifteen already expected to come under fire for turning upside down the Western notions of what an art exhibition should be. For a start, artistic and politically active collectives took the fore, effacing individual artists. Western (i.e., European and North American) output was nowhere to be seen. Instead, the curatorial arc spanned the world’s ‘South’ (which used to be called ‘Third World’) and the work of minorities, such as the Roma but also refugees, the queer community, and neurominorities.

Months before documenta’s opening, German media started questioning the inclusion of a Palestinian artists’ group, the Question of Funding collectiveExternal link, associated with the BDS External link(Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions) movement that is strongly critical of Israeli occupation.

Anticipating some sort of backlash from the tone of the criticisms, the curators set a debate panel called ‘We need to talk – Art – Freedom – Solidarity’ in the programme, meant to address the antisemitism issue and bring it in a broader perspective related to colonialism and racism. However, pressure of the Central Council of Jews in Germany led to the cancellation of the cycle of debates in early May.

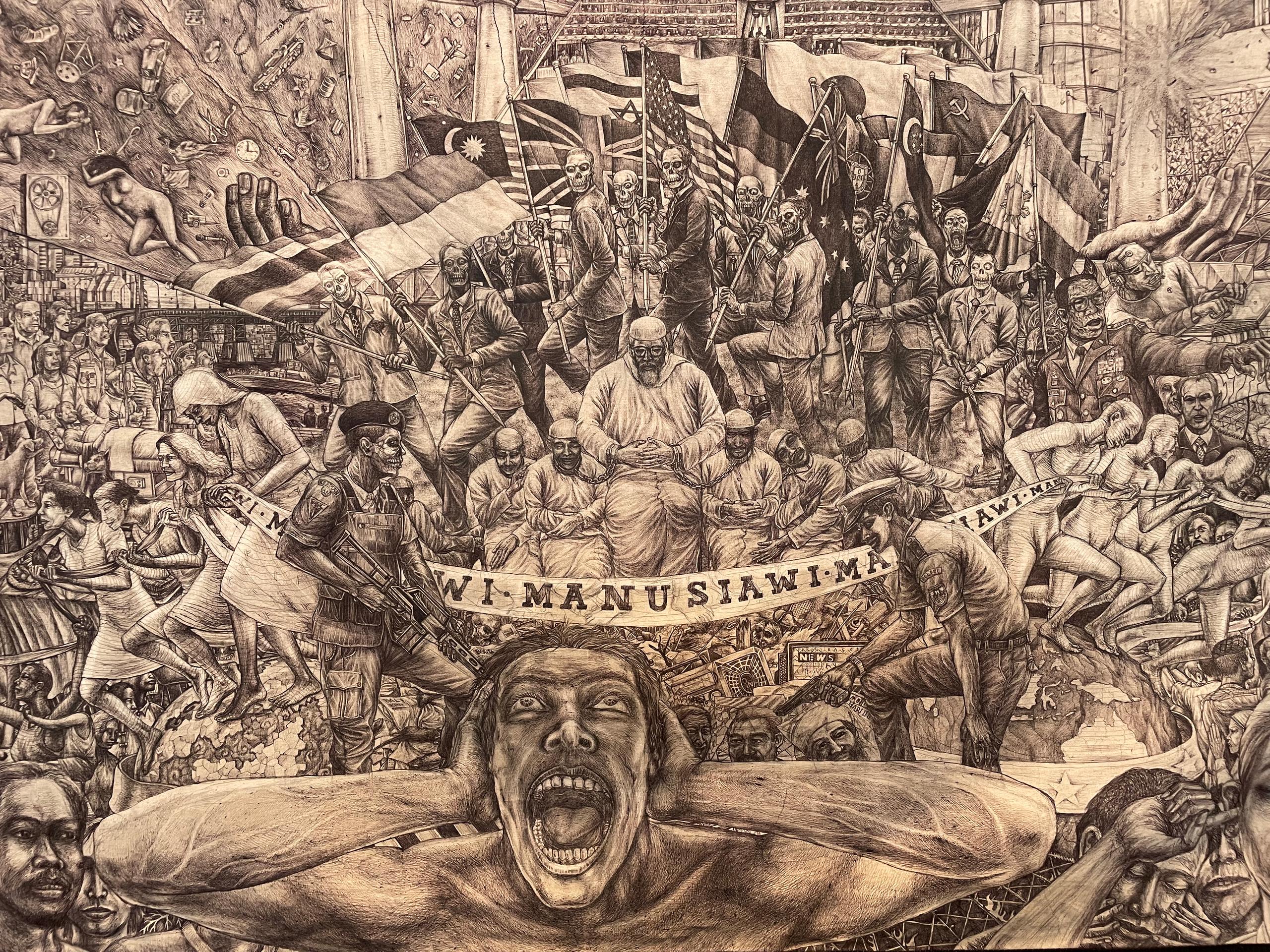

Then, a few days after the opening in June, Jewish groups, German media, and government officials decried a mural by the Indonesian collective Taring Padi in which a very unkosher pig wears a helmet emblazoned with ‘Mossad’ and a man in sidelocks recalling an Orthodox Jew dons a black hat with the SS insignia. In July, documenta’s supervisory board issued a strong statement, pulled the mural out of the exhibition, and duly fired its general director, Sabine Schormann.

There is no substantial Jewish community in Indonesia; the “Jew” and the “Mossad” are thrown in the mural together with all the international, reactionary agents that supported the Suharno dictatorship – which is the main subject of the mural. And the imagery used was actually coined in Europe along centuries of antisemitic prejudice.

The German discomfort became evident in the ensuing mediatized debate. These dismal images had the effect of a mirror to the German and European viewer, a mirror of the continent’s own ingrained antisemitism that tries to atone itself with an unflinching, and deeply problematic, defense of Israel’s state policies.

A Swiss perspective

The Swiss participation in documenta fifteen was limited to one single member of a collective (among other 1,500 participants) and the support of the Swiss arts council Pro Helvetia. However, Swiss artists and curators played a fairly outsized role, relative to the size of the country, in the documenta history (see box at the end of this article).

Besides, ruangrupa’s approach is a call to awareness directed not just to the German public and institutions, but also to a whole European and ‘Western’ cultural edifice, built upon notions developed throughout centuries of colonial and imperialistic history in which Swiss mercenaries, enterpreneurs, and capital played a big role.

The choice of ruangrupa was seen as a new, fresh start. To the German institutions’ credit, it must be noted that never before has any relevant and deep-pocketed Western contemporary art show opened its space with free rein to those genuinely stemming from the Global South and not belonging to its ‘westernized’ elites, as was the case with documenta 11’s artistic director, the Nigerian Okwui Enwezor.

The West is no more the best

Concepts such as ‘post-colonial’ or ‘post-gender’, for example, are normal currency in Western cultural debate, institutions, and universities. In ruangrupa’s position, these terms acquire material reality in the daily plights of disenfranchised communities, and material solutions in self-empowered collectives.

The same can be said about the questions over the primacy of the artist and the fabrication of artistic ‘geniuses’. It is a stated fact even in the West that the age of big names like Picasso or Van Gogh is over, but the art schools keep throwing thousands of new artists in the market every year with the ambition to strike a great deal with a powerful gallery and make his or her or their names a staple of private or public collections.

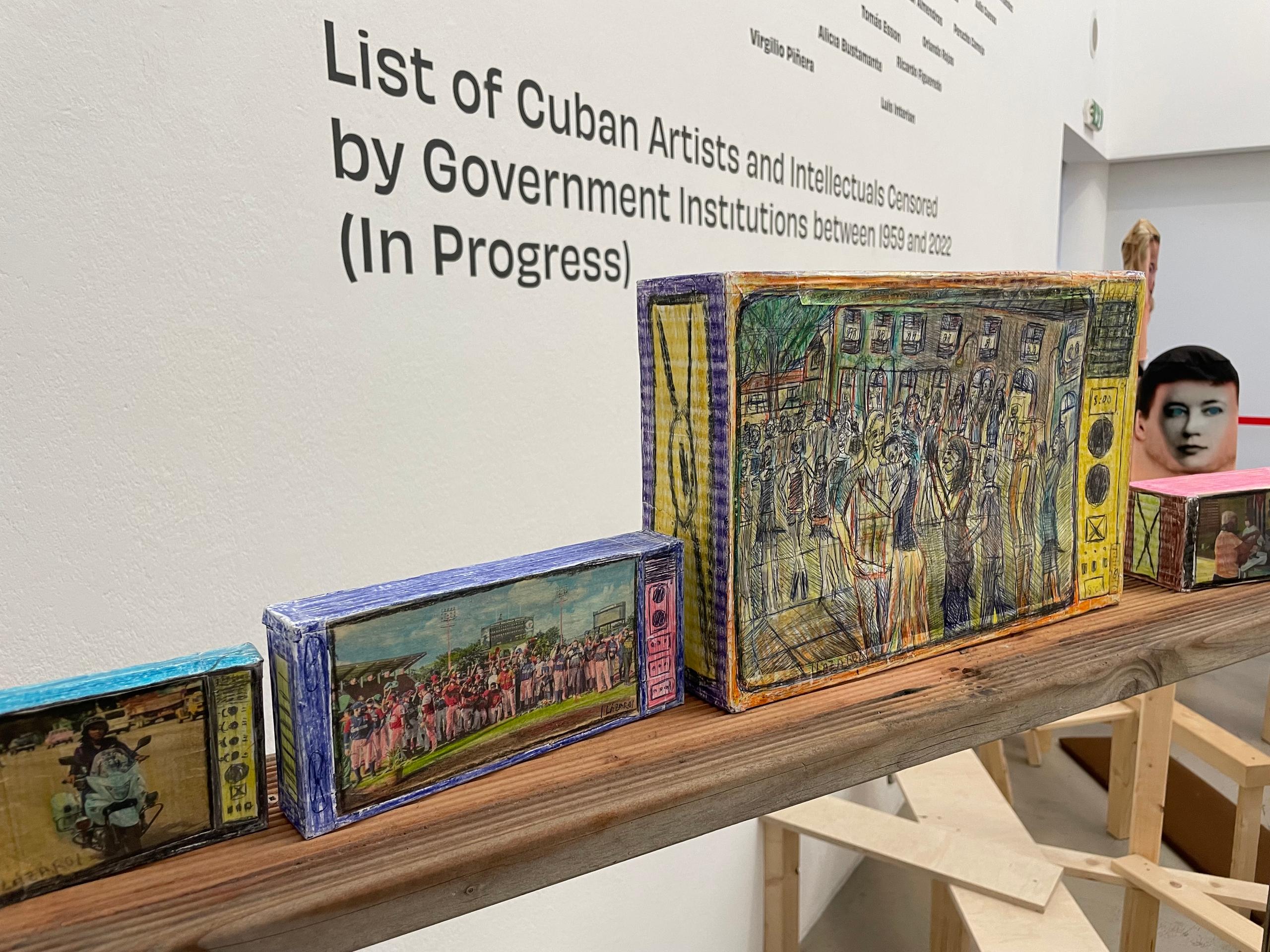

ruangrupa, though, makes it clear that there would be no Asian Matisse or an African Beuys in their show. Instead, what we see is that even established artists, such as the Cuban Tania Bruguera, merrily effaced their individual names under the auspices of the collectives in which they take part (in Bruguera’s case, the Hannah Arendt International Institute of Artivism – INSTAR).

Lumbung is the word

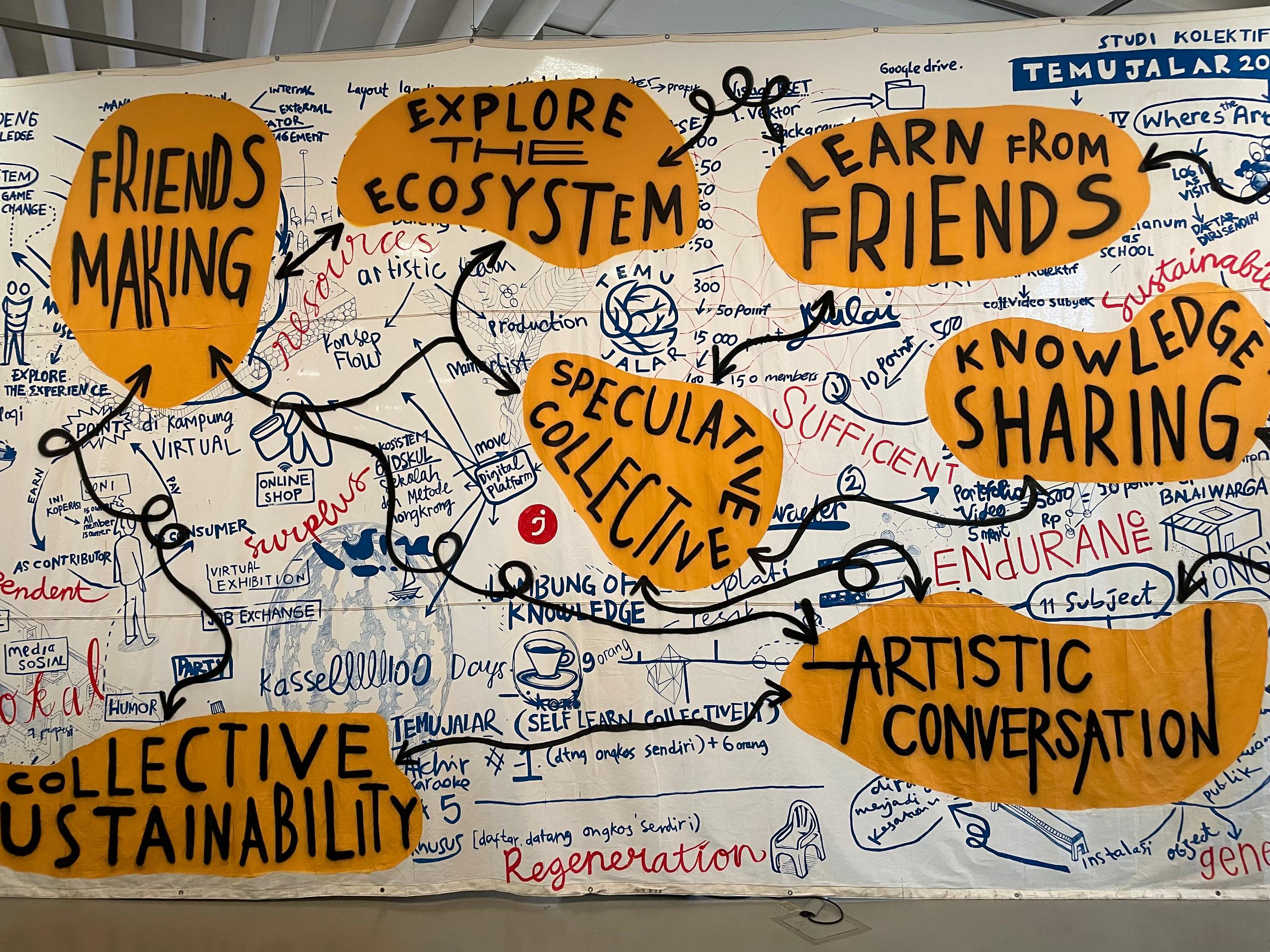

“Lumbung” is documenta fifteen’s keyword. It is an Indonesian word for a “communal rice-barn, where the surplus harvest is stored for the benefit of the community”. ruangrupa extended the meaning to all kinds of collaborative work, going beyond the anarchist concept of “mutual aid”. In fact, this is a practice all over the world and sustained not just by art collectives or as an alternative fad of the so-called generation Z (the one reaching adulthood in the 2010s). Art here is just one of the tools, mixed in social projects and political activism, used by networked collectives.

documenta fifteen opened lots of windows into how people in impoverished societies do and think art. Contrary to the Western notion, where art has lost its spontaneity for the sake of technical prowess and is enclosed in its own technical realm (paraphrasing the critic Boris Groys), ruangrupa brings a world where art is undissociated from the popular culture and daily life. Where there are no public or private grants, generous foundations, or richly endowed art schools.

In these realities, the collective is not a matter of ideology but of sustainability and survival. The Turkish-German curator Ayse Gülec stresses that the whole documenta fifteen was made according to these principles. “Lumbung is not a metaphor here, we really worked based on its principles of collaboration and solidarity”, she says.

The artworks are deeply related to political, environmental, and social issues. But differently from the usual tone of denunciation in political art, these lumbung activists and artists are seriously (though not necessarily successfully) looking for solutions to the issues they raise.

This form of organization also affected more mundane and practical questions. Alexander Supartono, a member of the Taring Padi collective (the one at the center of the antisemitism debate), told SWI that the documenta administration didn’t know how to pay the artists, for example. After all, the collectives do not have bank accounts. “Punctuality is another prison”, he says, but despite these little glitches, the experience as a whole left definitive marks. “documenta made us much stronger”, he says, “we validated our ways of working, collaborating, and spreading solidarity.”

Visitors were certainly challenged by a grand exhibition that in many instances looks like naïve works of art students. At certain points the show sounds indeed a bit flat, lacking the depths with which contemporary art is usually associated. Or even too reliant in rhizomic diagrams that confound more than illuminate the works on display. But still, it showed that another way of looking at and working on the world is possible – and necessary.

Ranked among the world’s premier showcases of contemporary art, together with the Venice Biennale, many of the documentas were marked by a compelling grip on the pulse of the times, and also for setting, or consolidating trends, lifting them from the undercurrents of the art circuit to the big public.

It was not planned to be like that originally. documenta started in the early 1950s, within the mindset of the Cold War, as a private initiative looking for state support in order to cleanse the shadow cast over modern art during the Nazi regime.

In its first four editions (1955, 1959, 1964 and 1968) it was a showcase of ‘free’ abstract and early pop art intended as a counterpoint to state-sanctioned Socialist Realism pervading the Communist bloc. Gathered around the designer Arnold Bode, a club of eminent gentlemen – art historians, museum directors, and industrialists, many of them sharing a past of dutiful service to the Third Reich (though not Bode himself) and ‘denazified’ for dutiful service against communism – conceived and ran documenta as a showcase of eminently Western art.

Bode’s exhibition designs revolutionized the art shows of that time, expanding the art experience to the corridors, cafeterias, and public spaces. However, the boundaries between art show and art fair were quite porous.

Borrowing from ideas devised by Swiss artist Dieter Roth, among others, the documenta organizers pioneered the sales of limited editions of prints and graphic art with astounding commercial success. Eventually, budgetary issues and conflicts of interest wore out the initial setup of documenta.

documenta 5, in 1972, set the show on a new, and fairly radical direction. The structure was totally revamped: documenta would not be an art fair anymore, the state (on a municipal, provincial, and federal levels) would step in more vigorously, its administration would be run by a hired professional staff, and each edition, to be held every five years instead of four, would have a different artistic director.

The world after Harald Szeemann

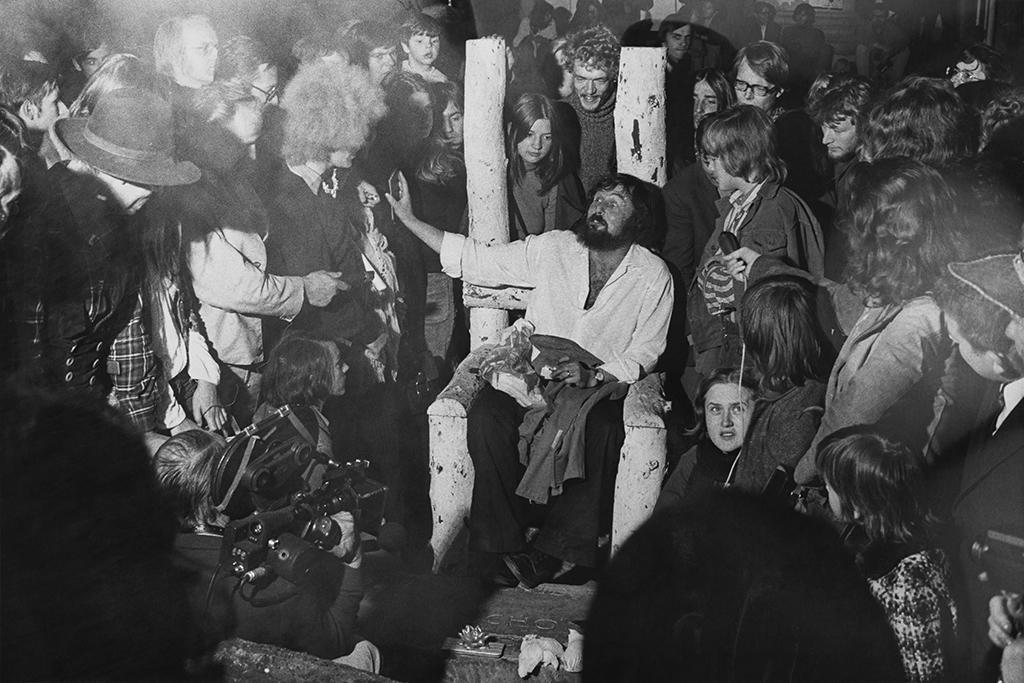

At the helm of this new concept, the Swiss curator Harald Szeemann hedged the commercial interests of the older members of the board and consolidated the role of the Curator. Szeemann brought to documenta the experience of almost a decade running the Kunsthalle Bern, where his landmark exhibition “Where attitudes become form” (1969) gave leeway to radical displays of conceptual art (and cost him his job in Switzerland).

In documenta 6 (1977) the German artistic director Manfred Schneckenburger introduced photography and video, that were not yet considered as relevant artistic media, in the art space. In documenta 8, ran again by Schneckenburger (the only case of a curator doing two editions), the show expanded beyond the pure realm of art to address the question of social design (“The Social Dimension of Art”).

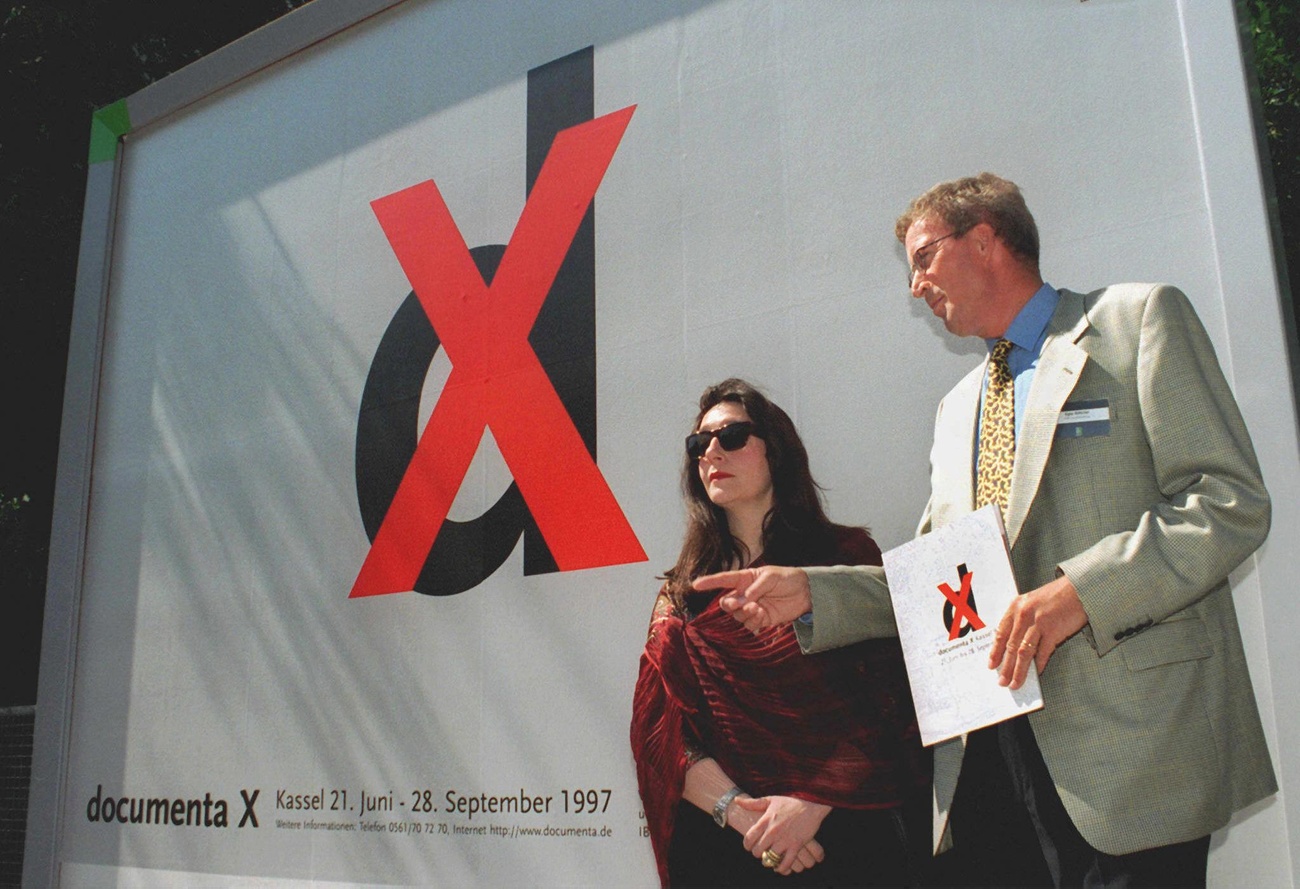

The last documenta of the 20th century (documenta X, 1997) had a lasting impact. The artistic direction was placed in the hands of a woman, and a non-German speaking one, for the first time. The French curator Catherine David’s cross-discipline approach was not shy of engaging with political art (the Cold War was over, after all) and centered her attention to the dichotomy ‘center vs. periphery’. Besides, she also commissioned the first website for a grand art exhibition, designed by the Swiss artist Simon Lamunière.

If Catherine David was the first woman, the Nigerian Okwui Enwezor was the first non-European. His documenta 11, however, deflated expectations with a very restrained show, not making use of public spaces, and privileging the “white cube” format of art galleries. Enwezor would quickly become one of the most influential curators in the global art scene until his untimely death in 2019, at the age of 55. His Venice Biennale in 2015 (‘All the World’s Futures’) is considered one of its best editions ever.

Going global, in space and time

In 2007, a until then relatively unknown couple of curators, Roger Buergel and Ruth Noack, globalized documenta 12 in time and space. Seeing the evolution of art as a “migration of forms”, the duo challenged the traditional categories of art history, finding links and unsuspected references between artworks of disparate regions and ages. After documenta, Buergel continued developing his concept at the Johann Jacobs Museum in Zurich.

The last documenta, number 14, directed by the Polish curator Adam Szymczyk, split the show in two main venues, Kassel and Athens. The choice of the Greek capital was not by chance, as the continent was reeling from the explosive numbers of refugees reaching European, and mainly Greek shores as a result of conflicts in Syria, Afghanistan, Lybia and Sudan. Besides, this crisis coincided with the Greek debt crisis, pitting the country in direct confrontation with an EU bureaucracy led by Germany. Szymczyk, who lives in Zurich, carried further the positions developed in other documentas to the possible limits of European perception. It was well conceived with the best intentions, but it still couldn’t overcome the Western perspective.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.