Listening to the voices of the past

When Thomas Alva Edison first succeeded in capturing the human voice on a phonograph, the ability to record speech opened up a brave new world for linguists.

The prolific American inventor achieved this feat in 1877. More than 30 years later the Phonogram Archive of Zurich University joined the technical revolution.

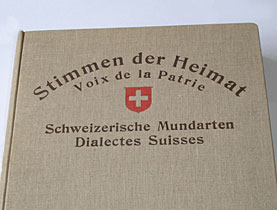

To mark its centenary this year, the archive is publishing a new CD edition of the legendary Voices of the Homeland, a collection of audio recordings of Swiss dialects, first produced in 1939 to boost the patriotism of the Swiss abroad.

The recordings offer more than just an opportunity to hear old, and in some cases extinct, dialects. They also document the technical progress made in sound recording in the course of a century.

The Voices of the Homeland provide insight into the national attitude towards dialects in Switzerland.

New field

The recording technology made it possible to establish dialects, which had no written form, as a subject for sociolinguistic research. “The early 20th century Zurich University researchers wanted to document Swiss dialects,” Michael Schwarzenbach of the Phonogram Archive said.

The Viennese German scholar Joseph Seemüller was one of the first to record a collection of German dialects on wax disks, and he sent the book he published about it to Zurich.

This sparked the interest of Albert Bachmann, professor of the German language in Zurich, who wanted to borrow such a device. In June 1909 the first independent recordings were generated at Zurich University.

Lost Yiddish

“They wanted to capture dialects that were dying out. We have recordings of Walser dialects in northern Italy, that have practically died out today. We also have Surbtal Yiddish. The villages of Endingen and Lengnau in canton Argau were two communities where a special kind of Yiddish was spoken.”

The first recording, made in Zurich, was of the Swiss-German dialect spoken in canton Glarus. A student, Catharina Streiff, read a statement in the dialect into the cardboard funnel of the phonograph. From 1910 researchers began collecting not just the German dialects but the other three national languages too.

In 1932 the Phonogram Archive finally bought its own recording device, with which it could record voices on gelatine foils. The diverse recordings made with it were not fully reliable. Therefore high-quality recordings were produced in a professional studio for the 1939 National Exhibition in Zurich.

Patriotism

“There was a certain buzz around the national dialects in the 1930s. It was also a part of the national defence against Germany. It was decided to make a collection of national dialects, dedicated to the Swiss abroad,” Schwarzenbach explains. It was a way to make them feel more closely tied to the homeland.

The Voices of the Homeland were described in lofty terms in the text accompanying the recordings.

“It is not enough that we feel bound together by the voices of our fellow citizens, we should – and that happens when you listening devoutly – fall under the spell of our ethnic, homely forms of expression and under the spell of the real Swiss way of thinking.”

The sound of home

The 18 disks obviously achieved their goal with the Swiss diaspora. The production was certainly enthusiastically endorsed by its distributors.

“The Swiss abroad will be enriched in a beautiful and meaningful way through this work. The ancient sound of the homeland is speaking here. No Swiss person abroad will be immune to the mystical effect of these sounds,” one wrote.

At the National Exhibition in Zurich in 1939 the disks were exhibited in the universities hall. To help visitors follow the recordings, books of text were also distributed.

The exhibition, which attracted 10.5 million visitors, appealed to the hearts and minds of the Swiss people, arming them for the “mental defence of the nation”, as it became known.

“We know from the records that the Apenzell dialect was the most popular at the Landi [National Exhibition],” Schwarzenbach said. The dialect of Bosco Gurin – a German-speaking village in Ticino – was the most interesting for the researchers.

The map used at the exhibition to show where all the dialects had come from has been lost but the Voices of the Homeland will be rereleased on CD in November.

New technology

In 1948 the Archive bought two Webster Wire Recorders, on which sound was recorded magnetically on a thin steel wire. These machines were also used for the first recordings of the Language Atlas of German-speaking Switzerland.

Later the machine was given on loan to Bern University, which only used it to make second sets of recordings because the new magnetic tape method was not yet fully trusted.

The advent of digitalisation of sound technology in the 1970s brought undreamed of possibilities to dialectology. “They could now go directly to people’s homes with the equipment without a problem, and there was no more need to invite people to the studio.”

The archive still carries out recordings on a project basis. There is not enough money for nationwide dialect research today.

Eveline Kobler in Zurich, swissinfo.ch (adapted from German by Clare O’Dea)

Switzerland has four national languages, German, French, Italian and Romansh.

The spoken forms of the German of Switzerland and the German of Germany became differentiated in mediaeval times.

Spoken Swiss German is largely unintelligible in most of Germany.

There are three main German dialect divisions within Switzerland – although each spills over into the border areas of neighbouring countries.

Apart from a slight difference in accent and vocabulary, the French spoken in Switzerland today is similar to that of France and to the written language.

However, the language originally spoken in western Switzerland was not French but Franco-Provençal, which was also spoken in eastern France and northern Italy. It survives, with difficulty, in local patois, which exist in a range of local variations.

Switzerland’s Italian speakers, in canton Ticino and parts of canton Graubünden, use standard Italian, but in private many speak a dialect of western Lombard, the unofficial language of northern Italy. This dialect exists in many local variations.

Romansh, spoken in parts of canton Graubünden, exists in five distinct spoken forms, known as “idiomas”, each of which also has a written version. The idiomas also have their own dialects. An artificial written language, Romansh Grischun, was introduced as an umbrella form in 1982 and is used for official documents.

The 1939 collection includes recordings of 34 Swiss dialects.

Speakers are heard reading texts in prose and verse of well known dialect writers.

All of the cantons are represented.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.