Returned art works fill missing gap

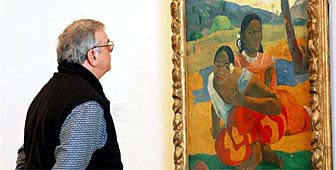

Seventeen masterpieces are back on display in Basel after spending nearly five years in exile in the United States.

“They were very much missed,” says Bernhard Mendes Bürgi, director of Basel’s fine arts museum, the Kunstmuseum. “We have a wonderful collection of 20th century art, but where the late 19th century was concerned there were some gaps.

“These paintings, by such heroes of modern art as Gauguin, Cézanne and van Gogh, have refilled the gap and reinforced our collection.”

The paintings, by leading impressionists and classic modernists, are from a collection begun in the early 1920s by a Swiss businessman, Rudolf Staechelin. Over 50 years ago, its core was placed on long-term loan to the Kunstmuseum.

But in 1997 they were transferred by the Staechelin family foundation as a loan to the Kimbell art museum in Fort Worth, Texas, after the Swiss government signed the UNIDROIT international convention on the illegal transfer of stolen cultural objects from one country to another.

It should be added that the bona fide provenance of the collection has never been in question, and the “exile” was a protest – supported by all the major Swiss art museums – against UNIDROIT.

Uncertainty over property rights

Neither the Swiss nor the US government has ratified the convention, which had created uncertainty about property rights. It was feared that under its terms, nobody starting to buy art could be sure before the lapse of 50 years whether he or she really should be the owner.

The opponents’ view was that future art loans between countries would be jeopardised, and cooperation would suffer between the state and the private sector.

“I have always said that if the legal situation allows, I would like to bring the paintings back,” said a clearly delighted Ruedi Staechelin, grandson of the collection’s founder and president of the family foundation.

“There was a worst case scenario in which we feared that the collection wouldn’t come back because of legal complications,” he told swissinfo. “Every step we took was coordinated with the Basel city government. I wanted to be sure not to do anything which could be interpreted in a bad way.”

These steps began with the transfer of the paintings to a New York-based trust, which because the US had not ratified the convention meant that UNIDROIT did not apply. Therefore there was no threat of legal action.

Before 1997 the collection had been a Swiss loan to a Swiss museum. “Now it’s legally an American loan to a Swiss museum, and Switzerland would have problems forbidding the export of the property of a trust under New York law,” said Staechelin, who admitted – with an audible sigh – that the legal situation was extremely complicated.

by Richard Dawson

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.