Big Bang re-enactment begins

Physicists at the vast underground complex, Cern, near Geneva have taken the first step towards understanding the make-up of the universe on Wednesday.

Scientists fired a first beam of protons around a 27-kilometer tunnel housing the Large Hadron Collider (LHC). They hope to recreate conditions just after the so-called Big Bang.

After a series of trial runs on Wednesday morning, two white dots flashed on a computer screen at 10.26 local time indicating that the protons had travelled clockwise along the full length of the particle smasher, described as the biggest physics experiment in history.

“There it is,” project leader Lyn Evans said when the beam completed its lap.

Champagne corks popped in labs as far away as Chicago, where contributing and competing scientists watched the proceedings by satellite.

Five hours later, scientists successfully fired a beam anticlockwise. The plan is to smash particles together to create, on a small-scale, re-enactments of the event that started up the cosmos.

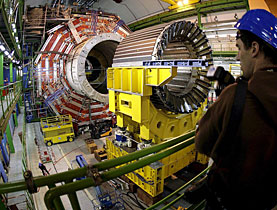

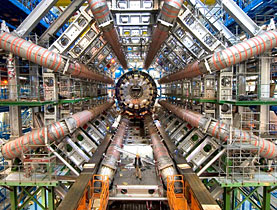

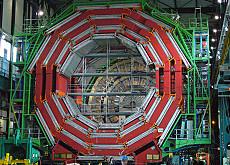

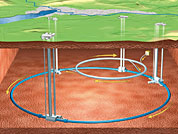

The LHC will use giant magnets housed in cathedral-size caverns to fire beams of energy particles around a 27-km tunnel where they will collide at close to the speed of light.

Computers will record what happens each time in these mini versions of the primeval fireball and the vast store of material gathered will be analysed by some 10,000 scientists around the globe for clues on what came next.

Scientists at Cern, the 54-year-old European Organisation for Nuclear Research, will pursue concepts such as “dark matter,” “dark energy”, extra dimensions and, most of all, the “Higgs Boson” believed to have made it all possible.

“The LHC was conceived to radically change our vision of the universe,” said Cern Director-General Robert Aymar. “Whatever discoveries it brings, mankind’s understanding of our world’s origins will be greatly enriched.”

“It’s part of the human condition to ask questions about where we come from,” physicist Ulrich Straumann, who represents Switzerland on Cern’s executive board, told the Swiss news agency earlier this year.

Cern scientists have been at pains to deny suggestions by some critics that the experiment could create tiny black holes of intense gravity that could suck in the whole planet.

14 billion years ago

Cosmologists say the Big Bang occurred nearly 14 billion years ago when an unimaginably dense and hot object the size of a small coin exploded in what was then a void, spewing out matter that expanded rapidly to create stars, planets and eventually life on Earth.

But the SFr10 billion ($9 billion) project begins with a relatively simple procedure: pumping a particle beam around the underground tunnel.

Technicians will first attempt to push the beam in one direction round the tightly sealed collider, some 100 metres underground.

Once they have done that – and Cern officials say there is no guarantee that success will come immediately – they will project a beam in the other direction.

And then, perhaps in the coming weeks, they will pump beams in both directions and smash the particles together albeit first at low intensity.

Heat is on

Later, probably near the end of the year, they will move on to produce tiny collisions that will recreate the heat and energy of the Big Bang, a concept of the origin of the universe that now dominates scientific thinking.

The detectors will monitor the billions of particles that will emerge from the collisions, capturing on computer the way they come together, fly apart or just simply dissolve.

It is in these conditions that scientists hope to find fairly quickly the Higgs Boson, named after Scottish scientist Peter Higgs who first proposed it in 1964 as the answer to the mystery of how matter gains mass. (A boson is a type of particle.)

Without mass, the stars and planets in the universe could never have taken shape in the aeons after the Big Bang, and life could never have begun on Earth or, if it exists as many cosmologists believe, on other worlds either.

The experiment is not without detractors.

Websites on the internet, itself created at Cern nearly 20 years ago as a means of passing particle research results to scientists around the globe, have promoted claims that the LHC will create black holes sucking in the planet.

“Nonsense,” say Cern and other leading scientists.

swissinfo with agencies

Cern was founded in 1954 by 12 states, including Switzerland, and now has 20 member states.

The LHC tunnel is 27km long and runs between Lake Geneva and the Jura mountain range. When it was excavated, its two ends met up within 1cm.

Cables for the LHC contain 6,300 “superconducting filaments of niobium-titanium” that are 0.006mm thick. In total, they stretch more than 10 times the Earth’s distance to the sun.

The LHC contains the world’s largest fridge. Its temperature is colder than deep space.

The LHC’s two proton beams will use as much energy as a 400-metric ton train travelling at 200 km/h.

The system’s magnet contains more iron than the Eiffel Tower.

Data recorded by the LRC will be enough to fill 100,000 DVDs each year.

Heads of state will attend the LHC’s official inauguration on October 21.

In the LHC, high-energy protons in two counter-rotating beams will be smashed together to search for exotic particles.

The beams contain billions of protons. Travelling just under the speed of light, they are guided by thousands of superconducting magnets.

The beams usually move through two vacuum pipes, but at four points they collide in the hearts of the main experiments, known by their acronyms: ALICE, ATLAS, CMS, and LHCb.

The detectors could see up to 600 million collision events per second, with the experiments scouring the data for signs of extremely rare events such as the creation of the so-called God particle, the yet-to-be-discovered Higgs boson.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.