An outsider at home, a master abroad: Jia Zhangke’s struggles to film the real China

Chinese director Jia Zhangke was a guest of honour at the 55th Visions du Réel International Film Festival in Nyon, Switzerland. He spoke to SWI swissinfo.ch about censorship, why Hollywood has fallen from grace in the Chinese market and how filmmakers should deal with AI.

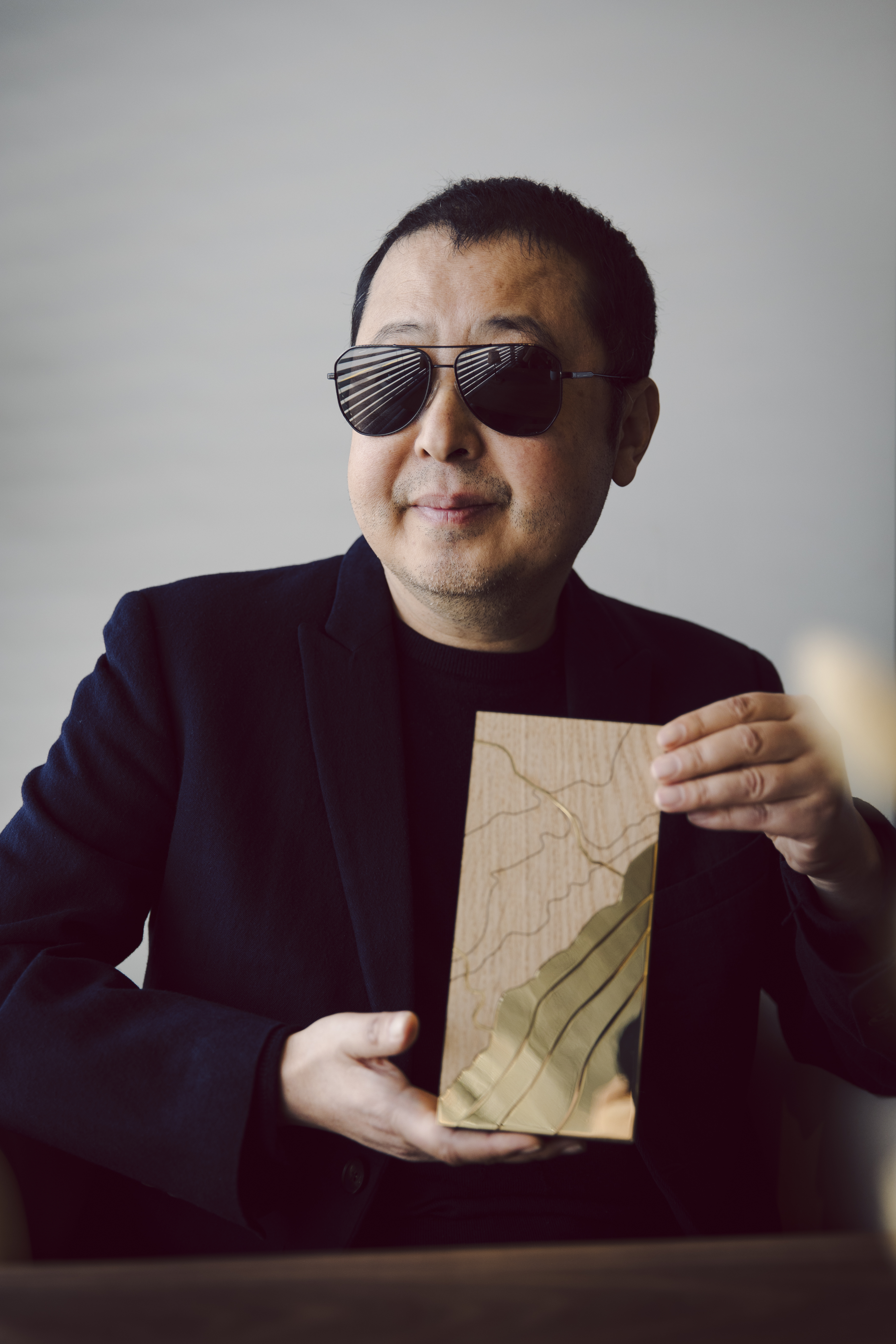

The day after Jia received his award, as “a leading figure in independent Chinese cinema and contemporary cinema more broadly,” I met him at the Ambassador Boutique Hotel in Nyon, smoking a cigarette at ease before he led me down to a quiet underground room.

“Underground” is nothing new for Jia. His feature “Xiao Wu” (Pickpocket, 1997)External link, which first brought him international fame and won six international awards while being fined and banned in China, was made with self-pooled funds. It was produced without government approval, and entered international film festivals without official authorisation.

Combining the compassion of Italian neorealism with the spirit of freedom and equality of the French New Wave, Jia delivered to the world “a veritable manifesto for a Chinese New Wave”External link and immediately established himself as a leading voice in Asian cinema.

In a conversation with SWI, Jia described the current reality of the Chinese film industry, which differs from perceptions of an industry crippled by censorship. Through personal interaction with Western filmmakers, he is trying to break down the invisible “Berlin Wall” – the product of the historical divide between the so-called “free world” and China, a country trapped in Western stereotypes. As renowned French director Claire Denis, Jia’s longtime friend, said at the award ceremony, “Jia helped me discover another, truer China – his own.”

SWI swissinfo.ch: Since the outbreak of Covid-19, this is your first trip abroad to participate in an international film festival. What changes have you noticed in the international film industry?

Jia Zhangke: I haven’t had any real exchange with foreign filmmakers and audiences for almost 4 years, but I see that the new generation of filmmakers and festival curators have brought many new focuses and unique perspectives to filmmaking. For example, transgender and women’s empowerment issues have become the focus of attention and heated debate in the international film industry. In contrast, Chinese films have paid little attention to the phenomena of the free choice of the transgender group and the lack of feminist consciousness in Chinese society.

SWI: In recent years, films produced in Japan and South Korea have been consistently successful at international film festivals and on Netflix. Why have directors from other East Asian countries been more successful in the international circuit compared to the Chinese?

JZ: China’s quarantine and epidemic control policies during the COVID-19 epidemic resulted in a four-year “time lag” for Chinese filmmakers in terms of international contacts, marketing, and distribution.

We often say that it takes five years to create a generation of filmmakers. Although some new Chinese directors are not inferior to their international peers in terms of their grasp of modern film language and their insightful understanding of local social themes, they were passive and closed during the epidemic. It will take some time for them to integrate into the international market.

In addition, compared with Japan and South Korea, China itself has a huge domestic demand for films, and many works can be fully digested by the local market. Unlike Japan and South Korea, where directors must seek extensive international cooperation to achieve a commercial return on investment.

SWI: Over the past decade it has been reported that China has tightened its control and censorship of movie content. Do you agree?

JZ: I think using the word “tighten” is a bit too simplistic and symbolic to describe the dilemma faced by Chinese filmmakers. A more precise description should be: sometimes tightening, sometimes relaxing, in a state of constant uncertainty.

The current restrictions on Chinese filmmakers depend mainly on public opinion. More specifically, the attitudes, opinions and emotions expressed by the public via the Internet have a direct impact on whether the Chinese government tightens or loosens its censorship on cultural creation standards. Based on the current public opinion, the Chinese government may prevent or delay the screening of certain films that are considered to involve sensitive issues or topics.

Two films on the same subject can have very different fates depending on the different submission timing for review. If the timing of a film’s submission coincides with a social controversy or crisis incident that triggers a public outcry, it is highly likely that it will not be approved by the official authorities.

Compromise is useless. Most of my movies made after 2004 can be released in China. This is not the result of compromise, but the result of persistence. As a film director, I must pay a certain price to stick to my original artistic intention, which means waiting several years for the storm of public opinion to die down and for the officials to relax their objections.

SWI: Hollywood movies had dominated Chinese theaters for more than two decades, but in recent years they have lost their grace, including Guardians of the Galaxy 3, Barbie, and Oppenheimer, all of which have flopped in the box office. Why, in your opinion?

JZ: In recent years, Hollywood has produced a large number of films, series and sequels, with limited innovation, which can easily lead to aesthetic fatigue among audiences. On the other hand, many Chinese films with realistic themes have resonated with local audiences through popular forms such as comedy. Since audiences can find echoes of their own realities in local films, they will naturally abandon foreign films that are far removed from their own lives.

This is also related to the changes in the Chinese film market. In the past, China’s box-office revenue used to depend on the big cities. Now the Chinese film market relies mainly on third- and fourth-tier cities, where audiences’ habits are very localised. Audiences from different regions in the same country are considerably different in their acceptance of themes and imported films. And not only in China, the Italian film market is also like this.

Audiences in first-tier cities prefer to watch original films with subtitles, while those in third- and fourth-tier cities prefer dubbed versions. Hollywood marketing companies should take those factors into account.

SWI: In the current context of the proliferation of personal media channels, streaming platforms, and AI, as a director who still insists on making documentaries and feature films, do you think there is still room for traditional filmmaking?

JZ: I have deep confidence that there is. Because film is essentially an art that relies heavily on technological innovation for aesthetic self-renewal. The birth of television in the 1920s, and the subsequent popularisation of satellite TV and home theaters have all brought opportunities for the film industry to improve its artistic techniques of expression.

China’s streaming media market has already proved that streaming cannot surpass films. On the contrary: a film will only bring streaming viewership if it has high box-office numbers.

As for the emerging “dark horse” of AI, some filmmakers are indeed very nervous and wary of it, believing that it will replace the work of a large number of screenwriters and actors and deal a devastating blow to the traditional production model. Last year’s six-month strike in the Hollywood film and television industry was a massive reaction against AI.

But we can also see that among all art forms, film has been the first to take the initiative to understand and use AI. Last year, I participated in the production of an AI short film that brought together Charlie Chaplin, Chinese director Fei Mu, and Italian Neorealism master Roberto Rossellini for a dialogue around the same table. From this perspective, I think the future of the film industry in the context of AI is promising.

Edited by Eduardo Simantob & Virginie Mangin

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.