Solzhenitsyn returns to Switzerland

Giant of 20th century Russian literature, gulag survivor and exile, Alexander Solzhenitsyn is a compelling subject for an exhibition.

At the Bodmer Foundation’s museum in Cologny near Geneva, visitors can absorb impressions from 2,000 pages of his writings, photos and other personal effects. A 500-page catalogue accompanies the exhibition.

The padded jacket the prolific writer kept from his gulag years is there too, a reminder of his journey to Stalin’s version of hell and back.

Solzhenitsyn’s widow Natalya came to Geneva to give her seal of approval to the exhibition. She was in no doubt about the significance of this presentation of his works.

“Our history counts two episodes in Switzerland: the ostracism and exile of the family from 1974 to 1976 in the country that once welcomed Lenin, and today, this exhibition initiated by the Bodmer Foundation, the only museum of manuscripts in the world,” she said at the launch of the exhibition.

The writer’s widow has dedicated herself to the enormous task of publishing her husband’s complete works, including numerous unedited texts. “Thirty volumes have already been published but he probably wrote tens of thousands of pages,” she said.

Entitled “Solzhenitsyn, the courage to write”, the exhibition boasts two key pieces: the manuscripts of the Gulag Archipelago (1958-1968) and of November 16th (1984-1987).

Precious loan

But how was it possible to convince Natalya, guardian of his work throughout their married life and since his death in 2008, to allow the Archipelago to leave its home in the Solzhenitsyn Foundation, situated in the family’s old Moscow apartment?

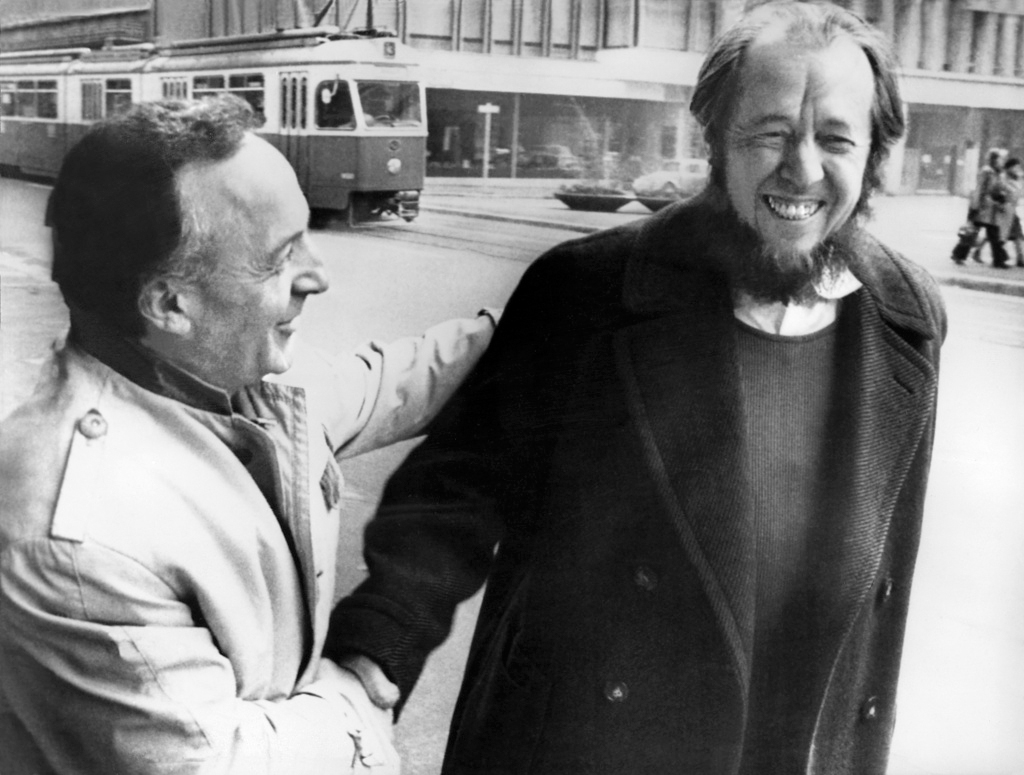

It took the persuasive skills of Georges Nivat, curator of the exhibition, personal friend of the Russian writer and translator of some of his texts into French, and professor emeritus at Geneva University.

“Yes it must have been hard for Natalya Dmitriyevna to let go of these unique manuscripts but we have given firm guarantees that they will return after six months,” he explained.

Nivat is also the author of the comprehensive 536- page catalogue, which brings together Solzhenitsyn’s personal archives , various texts, correspondence and newspaper articles, all richly illustrated and beautifully laid out.

All part of the fight

It was also Nivat who suggested that the Bodmer Foundation, which is celebrating its 40th anniversary this year, should pay tribute to a man for whom literature was “a relentless fight on behalf of all those who did not live to tell their tale”, according to the foundation’s director Charles Méla.

Having been a prisoner in the gulag from 1945 to 1953, “Solzhenitsyn conducted first an underground struggle, and later a public one, for the sake of the truth, to reveal to the world an unprecedented enterprise of slave labour.”

With the 1970 Nobel prize laureate, the foundation has finally chosen a “Russian pillar of the 20th century” to place alongside Homer, Dante, Goethe and Shakespeare.

Some 2,000 documents are displayed with reverence and elegance in the subdued lighting and crypt-like atmosphere of the basement of the Bodmer Foundation.

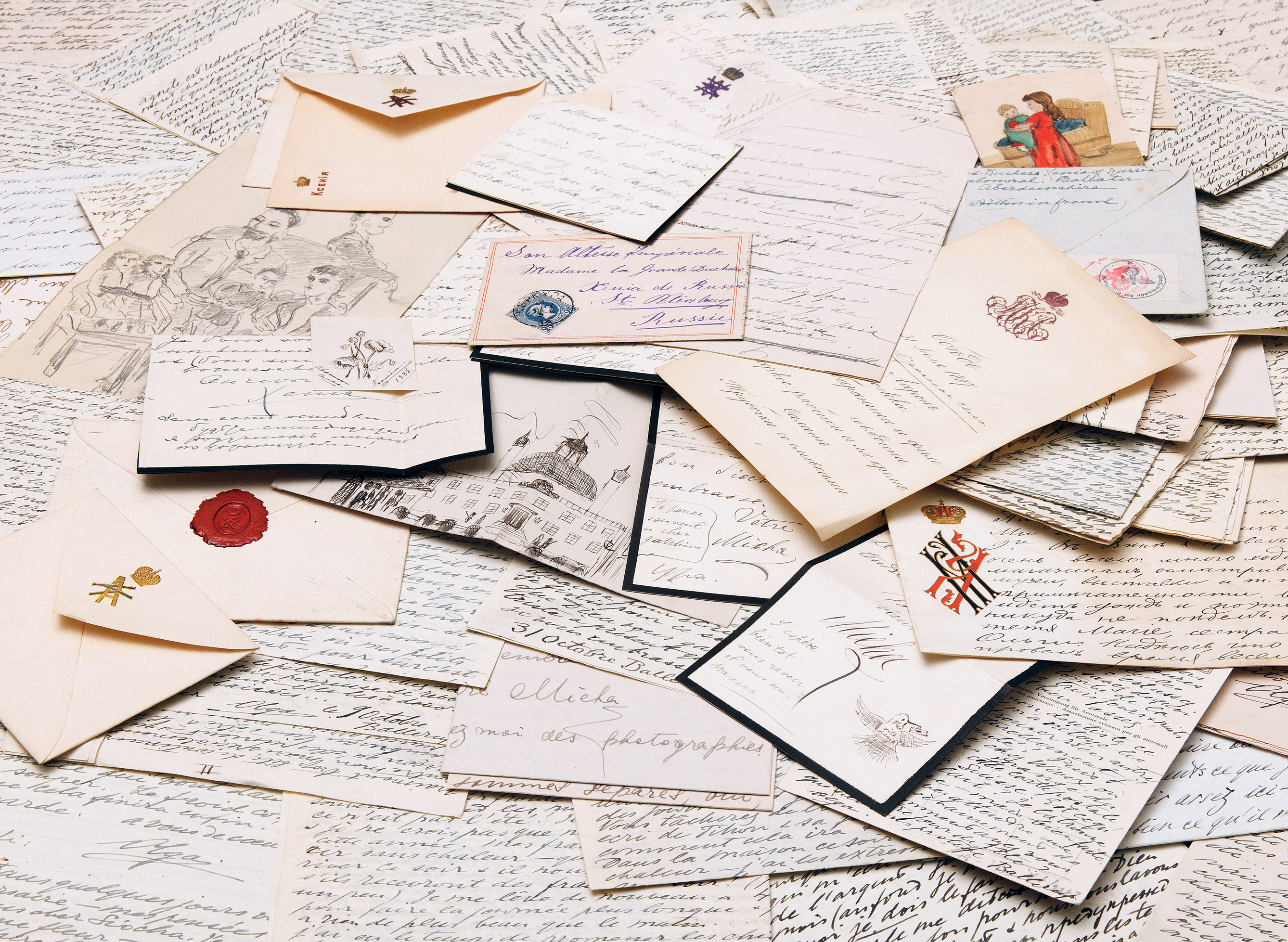

There is a wall of photographs, bordered by explanatory texts, cases containing manuscripts, miniscule “samizdat” texts (typescripts distributed underground in Soviet times), original editions, letters, articles and family documents.

The personal objects reflect the man. Pencils, glasses, a magnifying glass – the tools of the trade. And the famous padded jacket of the gulag, along with a hunk of bread pocketed during an arrest and conserved like a relic.

The gulag saga

Always fearful of arrest or raid by internal security, Solzhenitsyn kept only typewritten versions of his texts. Since the handwritten versions were usually burned after being typed up, “Russian” manuscripts are rare.

But the Archipelago was a notable exception, It was Solzhenitsyn’s first literary “monument to escape his uncompromising method of manuscript destruction”, says Nivat. The tribulations of this book, “launched like a torpedo against the Soviet regime”, mirror the story of the author’s combat against tyranny.

In fact, Nivat explains, the text was written in relative tranquility when he was staying with an Estonian former fellow inmate in the countryside, and it remained hidden there for 20 years. It was smuggled to France in 1968 on microfilm.

But the saga took a tragic twist in 1973, Nivat continues, when the volunteer typist who, without the author’s knowledge, had kept a copy of the book hanged herself after an search by the KGB who confiscated the text.

That prompted Solzhenitsyn to publish the book in Paris. The repercussions were swift and uncompromising. Solzhenitsyn was arrested and exiled with his family to the West, the first time he had been outside the USSR, other than during the Second World War.

How times have changed. “Alexander Solzhenitsyn, the courage to write” is included on the official programme of Russian culture in Switzerland organised this year by the Russian embassy to celebrate 65 years of diplomatic relations between the two countries.

Solzhenitsyn was born on December 11, 1918. He served in the Red Army in the Second World War but in 1945 was convicted for criticising Stalin’s conduct of the war, and spent the next decade in prison camps and internal exile.

He came to literary prominence in 1962 with “One Day on the Life of Ivan Denisovich”, a short novel based on his own labour camp experiences, the only work published in his homeland during Soviet rule.

For his later writings, published abroad, he was stripped of his citizenship and put on a plane to West Germany in 1974 for refusing to keep silent about his country’s past. Solzhenitsyn became an icon of resistance to the communist system from his American home in Vermont.

He received the 1970 Nobel Prize for Literature for a body of work including “The First Circle” (1968), and “Cancer Ward” (1968).

His monumental history of the Soviet police state, “The Gulag Archipelago”, was published in Paris in three volumes between 1973 and 1978.

He returned to Russia in 1994 and died in his home outside Moscow on August 3, 2008.

The Bodmer Foundation, which was set up by Swiss academic and collector Martin Bodmer in 1971, holds a collection of more than 160,000 manuscripts and books, dating from antiquity to modern times.

The collection includes first editions of major works, including the Papyrus 66, which is one of the oldest almost completely preserved manuscripts of the Gospel of St John , the original of Grimm’s Fairy Tales, the only copy of the Gutenberg Bible in Switzerland, a string quintet by Mozart, Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary, the manuscript scroll of The 120 Days of Sodom by the Marquis De Sade and original editions of Don Quixote and Faust, among others.

The Bodmer museum, designed by Ticino architect Mario Botta, is located at Cologny, near Geneva, and is open to the public. Its permanent exhibition is supplemented by four temporary exhibitions each year.

Alexandre Soljenitsyne – Le courage d’écrire (Alexander Solzhenitsyn – The courage to write) runs until October 16 at Fondation Martin Bodmer, 19-21 route du Guignard, Cologny (Geneva). Open Tuesday to Sunday from 2pm to 6pm.

(Translated from French by Clare O’Dea)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.