Taking home the dead

Ali Furat has anything but a nine-to-five job: his work involves repatriating the bodies of deceased Muslims to their homelands.

Furat handles around 400 repatriations each year and says that despite getting satisfaction from the job, the sense of sadness and loss is always there.

His company, Furat International Repatriation, is based in a Regensdorf industrial neighbourhood outside Zurich. Inside the offices the lights are low and on a shelf folders contain all the details about the people who are taken home for burial.

On the wall is a giant map of the world. Pins mark destinations such as Athens, Lima or Antalya. These are just a few of the places where Furat has partners.

In the 12 years since he founded the company, business has grown to the point where he no longer bothers to add pins to the board. Today, he has contacts on every continent.

Autumn and winter are the “high” seasons, since more people die at that time of the year.

“Many elderly and sick people don’t have the strength to get through winter,” the 47-year-old Turkish citizen told swissinfo. “It is also a period when people feel a lot of despair.”

Furat, who is married to a Swiss, began the job almost by accident. Some time ago he was part of a committee overseeing a fund for the repatriation of Turks.

But Muslims from other countries were coming to him for advice, especially when dealing with the authorities. Eventually in 1997 he decided to set up a business.

Open to all

“I seem to have slipped into this line of work and I can’t see how I can get out of it,” he said. But despite the irregular hours and the heavy workload he enjoys his job.

“I get a certain pleasure from being able to help people at a difficult time. When a woman loses her husband, for example, first there is grief, followed by stress and panic. How do you get a body back to a small village somewhere in Anatolia?”

This is where Furat steps in with his four employees. They take over the ritual cleansing and dressing of the body and deal with the formalities for its repatriation. “This is too much for most people, but for us it is part of our daily routine,” Furat explains.

His company repatriates Muslims from all over Switzerland to their homelands, but he does business with other religions too.

“We have already sent a Jew back to Turkey, a Mormon woman to Spain and recently a Catholic to Kosovo,” he said. “The Muslim community provides our core business, but we deal with everyone.”

Furat’s company also repatriates Swiss who have died abroad. It those cases his work involves close collaboration with the foreign ministry, insurers and local partners. “We usually repatriate more Swiss during the summer holidays,” he adds.

“Sad job”

Despite the routine and keeping a certain distance over the years, he can’t totally shut out the sadness involved in his line of work.

“I have a sad job,” Furat admits. “For some people, death is an end to everything. Others believe they will see each other again after dying. But we don’t know what to expect.”

He is particularly moved when an elderly person loses their lifelong partner.

“You see their wedding photos in their homes, pictures of when they were young and happy, at the star of their lives together. If one person dies suddenly, the other feels abandoned and lost, and to see that makes me sad.”

The worst for Furat is when a mother loses a child, no matter the age. He has never forgotten a scene at Bern’s University hospital, when a 72-year-old man died. At his side was a very elderly woman, stroking his hair, talking and crying.

“She was 94 and had lost her son,” Furat told swissinfo.

He cannot get used to such moments and tries to avoid them. “My heart should be made of stone,” he admits.

Swiss burial

Furat realises that sadness and a sense of loss go hand in hand with death, but he is also convinced that time helps overcome these feelings.

He says most people want to be buried where their family lives and where they grew up. He has met many Turks who moved to Switzerland in the 1960s to work but who want to be laid to rest in Turkey.

Furat wants to be buried in Switzerland though, in the Muslim section of a local cemetery. His wife and two children live here.

“I don’t want to take the pain and the sadness back to my family in Turkey,” he said.

swissinfo, Gaby Ochsenbein in Regensdorf

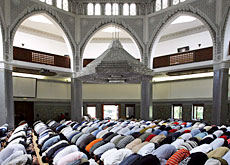

Islamic law calls for burial of the corpse, preceded by a simple ritual involving bathing and shrouding the body, followed by prayer. Cremation of the body is generally forbidden.

The deceased should be positioned so that the head is facing Mecca.

Loved ones and relatives observe a three-day mourning period. Mourning is observed in Islam by increased devotion, receiving visitors and condolences, and avoiding decorative clothing and jewellery. Widows observe an extended mourning period of 4 months and ten days.

Muslims are the largest religious group in Switzerland after the Christian faiths.

The 2000 census showed their numbers had more than doubled over the previous decade to 310,000. It is estimated that this figure now stands at around 340,000.

The rightwing Swiss People’s Party is currently campaigning to ban the construction of minarets in Switzerland.

In Switzerland, only the mosques in Geneva and Zurich have a minaret but they cannot issue the call to prayer. In addition there are around 150 “centres of worship” mainly in warehouses and old buildings, according to the Federation of Islamic Organisations in Switzerland.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.